Ice Age Teens Achieved Puberty at the Same Age as Modern Teens

It turns out the kids might be all right, contrary to what some people have been saying. A brilliant new study has revealed fascinating insights into the adolescent development of Ice Age teenagers from 25,000 years ago, shedding light on the timing of puberty in Pleistocene youths.

The research analyzed the bones of 13 ancient individuals estimated to be between 10 and 20 years old, to learn, among other things, that Ice Age teens were actually quite healthy.

‘Normal’ Puberty: The Time Frame of Pleistocene Adolescent Development

The researchers also learnt, crucially, that most of the individuals in the sample entered puberty at an average age of 13.5, reaching full adulthood between the ages of 17 and 22.

This timing is strikingly similar to that of adolescents in modern, affluent societies, suggesting that the onset of puberty has not significantly changed over millennia. These and other findings have emerged from the riveting new study published in The Journal of Human Evolution.

This collaborative research involved six institutions across multiple countries, including UVic in Canada, the University of Reading and University of Liverpool in the UK, the Museum of Prehistoric Anthropology of Monaco, and universities in Cagliari and Siena in Italy. The ongoing collaboration aims to deepen our understanding of the lives of Ice Age teenagers and their roles within their social structures.

The research analyzed the bones of 13 ancient individuals estimated to be between 10 and 20 years old. By examining these bones, researchers identified specific markers that allowed them to assess the stages of adolescence the individuals had reached at the time of their deaths.

“By analyzing specific areas of the skeleton, we inferred things like menstruation and someone’s voice breaking,” says University of Victoria (UVic) paleoanthropologist April Nowell, who co-led the study, in a press release.

Nowell explained that there is a common belief today that adolescents are entering puberty unusually early, often attributed to factors such as hormones in milk or environmental chemicals.

However, the research shows that Ice Age teenagers began puberty at roughly the same age as modern teens. This finding, she noted, suggests that instead of being an anomaly, today’s adolescents are actually following a developmental blueprint that has been consistent for thousands of years.

The innovative technique employed in this study was developed by lead author Mary Lewis from the University of Reading. Lewis’s methodology focuses on evaluating the mineralization of the canines and the maturation of bones in the hand, elbow, wrist, neck, and pelvis.

This detailed assessment enables researchers to pinpoint the stage of puberty achieved by each individual, offering a window into their developmental processes, reports The Daily Mail.

Understanding Prehistoric People Outside Tools

Contrary to the characterization of prehistoric life as “nasty, brutish, and short,” as famously described by philosopher Thomas Hobbes, this study has shown that Pleistocene teens were quite the opposite.

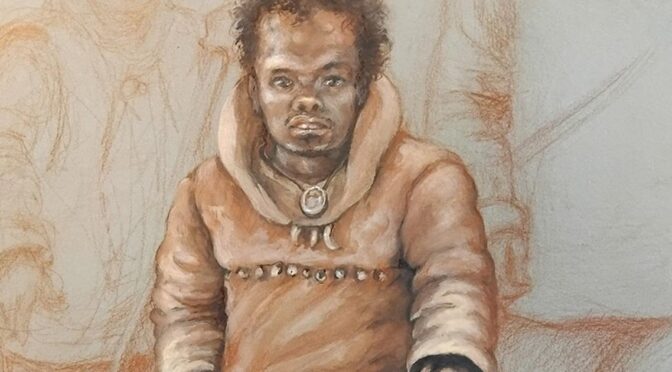

Among the skeletons examined was “Romito 2,” an adolescent estimated to be male and notably the earliest known individual with a form of dwarfism. The findings from this research provide further insights into Romito 2’s likely physical appearance and social role.

Midway through puberty, he would have experienced changes such as a deeper voice, akin to that of adult males, and the potential to father children. However, due to his short stature, he may have presented a youthful appearance with fine facial hair, which could have influenced how he was perceived by his community.

The research also revealed that teenagers who lived 25,000 to 40,000 years ago were highly active members of their communities. They contributed significantly by hunting, fishing, and gathering, playing a crucial role in helping their communities survive.

“The specific information about the physical appearance and developmental stage of these Ice Age adolescents derived from our puberty study provides a new lens through which to interpret their burials and treatment in death,” concludes archaeologist Jennifer French of the University of Liverpool, one of the co-authors of the study.