Priceless Ancient Bronze Statues Unearthed in Etruscan Baths of San Casciano dei Bagni, Italy

An “exceptional” trove of bronze statues preserved for thousands of years by mud and boiling water has been discovered in a network of baths built by the Etruscans in Tuscany.

The 24 partly submerged statues, which date back 2,300 years and have been hailed as the most significant find of their kind in 50 years, include a sleeping ephebe lying next to Hygeia, the goddess of health, with a snake wrapped around her arm.

Archaeologists came across the statues during excavations at the ancient spa in San Casciano dei Bagni, near Siena. The modern-day spa, which contains 42 hot springs, is close to the ancient site and is one of Italy’s most popular spa destinations.

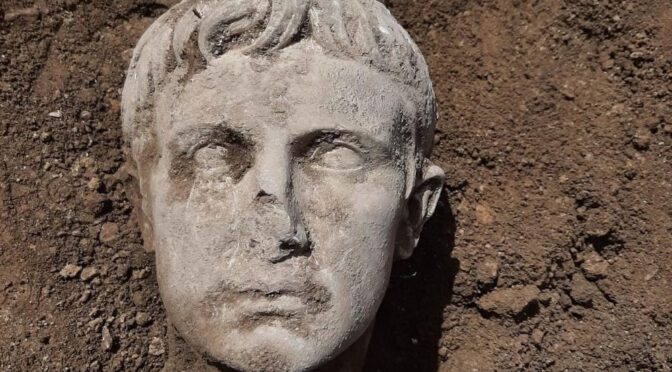

Close to the ephebe (an adolescent male, typically 17-18 years old) and Hygeia was a statue of Apollo and a host of others representing matrons, children and emperors.

Believed to have been built by the Etruscans in the third century BC, the baths, which include fountains and altars, were made more opulent during the Roman period, with emperors including Augustus frequenting the springs for their health and therapeutic benefits.

Alongside the 24 bronze statues, five of which are almost a metre tall, archaeologists found thousands of coins as well as Etruscan and Latin inscriptions. Visitors are said to have thrown coins into the baths as a gesture for good luck for their health.

Massimo Osanna, the director general of museums at the Italian culture ministry, said the relics were the most significant discovery of their kind since two full-size Greek bronzes of naked bearded warriors were found off the Calabrian coast near Riace in 1972. “It is certainly one of the most significant discoveries of bronzes in the history of the ancient Mediterranean,” Osanna told the Italian news agency Ansa.

The excavation project at San Casciano dei Bagni has been led by the archaeologist Jacopo Tabolli since 2019. In August, several artefacts, including fertility statues that were thought to have been used as dedications to the gods, were found at the site. Tabolli, a professor at the University for Foreigners of Siena, described the latest discovery as “absolutely unique”.

The Etruscan civilisation thrived in Italy, mostly in the central regions of Tuscany and Umbria, for 500 years before the arrival of the Roman Republic. The Etruscans had a strong influence on Roman cultural and artistic traditions.

Initial analysis of the 24 statues, believed to have been made by local craftsmen between the second and first centuries BC, as well as countless votive offerings discovered at the site, indicates that the relics perhaps originally belonged to elite Etruscan and Roman families, landowners, local lords and Roman emperors.

Tabolli told Ansa that the hot springs, rich in minerals including calcium and magnesium, remained active until the fifth century, before being closed down, but not destroyed, during Christian times. The pools were sealed with heavy stone pillars while the divine statues were left in the sacred water.

The treasure trove was found after archaeologists removed the covering. “It is the greatest store of statues from ancient Italy and is the only one whose context we can wholly reconstruct,” said Tabolli.

The recently appointed Italian culture minister, Gennaro Sangiuliano, said the “exceptional discovery” confirms once again that “Italy is a country full of huge and unique treasures”.

The relics represent an important testament to the transition between the Etruscan and Roman periods, with the baths being considered a haven of peace.

“Even in historical epochs in which the most awful conflicts were raging outside, inside these pools and on these altars the two worlds, the Etruscan and Roman ones, appear to have coexisted without problems,” said Tabolli.

Excavations at the site will resume next spring, while the winter period will be used to restore and conduct further studies on the relics.

The artefacts will be housed in a 16th-century building recently bought by the culture ministry in the town of San Casciano. The site of the ancient baths will also be developed into an archaeological park.

“All of this will be enhanced and harmonised, and could represent a further opportunity for the spiritual growth of our culture, and also of the cultural industry of our country,” said Sangiuliano.