1,600-Year-Old Roman Merchant Ship Cargo Discovered off Caesarea Coast

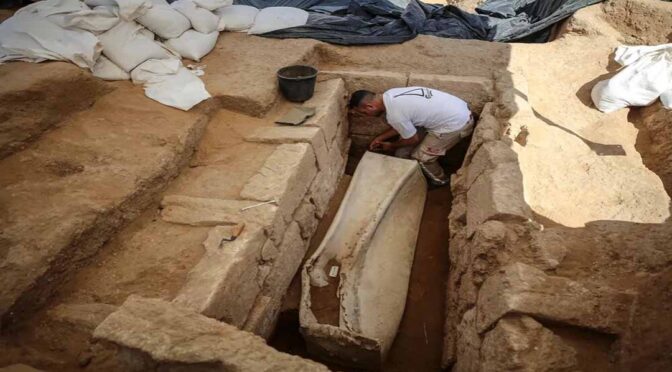

In recent times, divers have discovered some rarity of archaeological artifacts on the bottom of the sea off the coast of Israel in Caesarea.

The objects that seem to have been part of a Roman merchant ship cargo that sank some 1,600 years ago include coins, bronze statues, equipment used in running the ship, such as anchors, and numerous decorative items.

The treasure trove was discovered by accident by two amateur divers from Ra’anana, Ran Feinstein, and Ofer Ra’anan, who were swimming in the ancient harbor.

Upon emerging from the sea, they immediately contacted the Israel Antiquities Authority. Since then, the IAA’s marine archaeology unit has been conducting an underwater excavation of the site, in cooperation with the Rothschild Caesarea Foundation.

Among other finds, the cargo of the ship, which sank in the latter years of the Roman Empire (27 B.C.E. – 476 C.E.), included a bronze lamp depicting the image of the Roman sun god Sol; a figurine of the moon goddess Luna; a lamp resembling the head of an African slave; parts of three life-size bronze statues; a bronze faucet in the form of a wild boar with a swan on its head; and other objects in the shape of animals.

Also unearthed were shards of large containers used for carrying drinking water for the ship’s crew.

One of the biggest surprises was the discovery of two metallic lumps each composed of thousands of coins, in the shape of the ceramic vessel in which they were transported before they oxidized and became stuck together.

The coins bear the images of Constantine, who ruled the Western Roman Empire (312 – 324 C.E.) and was later known as Constantine the Great, ruler of the entire Roman Empire (324 – 337 C.E.), and of Licinius, a rival of Constantine’s who ruled the eastern part of the empire and was slain in battle in the year 324 C.E.

According to Jacob Sharvit, director of the IAA’s marine archaeology unit, and his deputy Dror Planer, “These are extremely exciting finds, which apart from their extraordinary beauty, are of historical significance.

The location and distribution of the ancient artifacts on the seabed indicate that a large merchant ship was carrying a cargo of metal slated to be recycled, which encountered a storm at the entrance to the harbor and drifted until it smashed into the seawall and the rocks.”

A preliminary study of the iron anchors unearthed at the site suggests that there was an attempt to stop the drifting vessel before it reached shore by casting them into the sea; however, the anchors broke, which constitutes “evidence of the power of the waves and the wind in which the ship was caught up,” say the researchers.

The discovery comes just a year after a trove of over 2,000 gold coins, dating to the Fatimid era about 1,000 years ago, was found nearby by divers and IAA staff. The coins are currently on public display in the Caesarea marina.

“A marine assemblage such as this has not been found in Israel in the past 30 years,” Sharvit and Planer explain. “Statues made of metallic materials are rare archaeological finds because they were always melted down and recycled in antiquity.

When we find bronze artifacts it usually occurs at sea. Because these statues were wrecked together with the ship, they sank in the water and were thus ‘saved’ from the recycling process.”

The archaeologists said the underwater treasures were discovered because of the diminishing amount of sand in the Caesarea harbor as a result of construction along the coastline south of the site, and due to the increased mining of sand – as well as the growing number of amateur divers in the area.

The IAA praised the two amateur divers for their good citizenship in reporting their findings and announced that they would accordingly be awarded certificates.