135-Year-Old Message In A Bottle Found In Floorboards – Amazing Victorian Time Capsule

A rather incredible discovery occurred in Edinburgh, Scotland, where a woman found a 135-year-old message in a bottle under her floorboards.

Everything started in October 1877 when two local workers left a note under the floorboards at a Morningside villa. The message was placed in a bottle and left untouched until now when Eilidh Stimpson, a mother of two found it in her Morningside home in Edinburgh!

“Stimpson couldn’t believe her eyes as she read out the hand-written message on the withered note, which had been rolled up inside an empty whisky bottle since the day the floor was laid.

The Victorian time capsule was discovered on Monday by local plumber Peter Allan who just happened to cut through the exact place in the floorboards where it had been left on October 6, 1887,” the Edinburgh Live reports.

“It’s pretty cool,” Eilidh, who works as a GP, told Edinburgh Live. “And so lucky as well, because we were meant to be moving a radiator from one side of the wall to the other. The plumber came and started cutting a hole and said it was going to be a bit of a nightmare as there was a floor on top of a floor.

“Then he came down the stairs going, ‘Look at what I just found in the hole I just made!’. It was quite exciting.”

Peter and Eilidh decided to until her children came home from school, and Eilidh’s partner returned from work before opening the bottle and reading the old message.

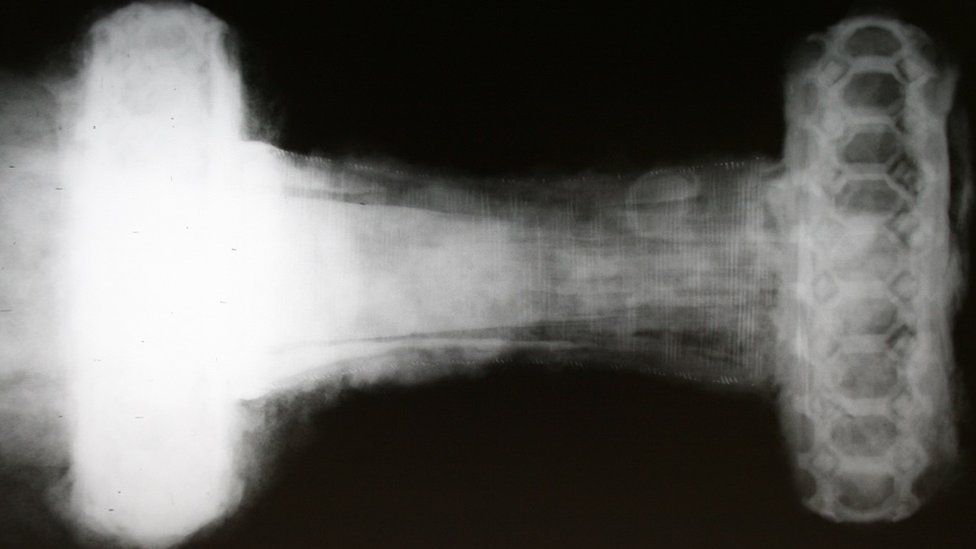

Together they tried to get the message out of the bottle, but it was easier said than done. There was no way to remove the old note without tearing it, so they had no other option than to break the bottle.

“Eilidh explained: “We were desperately trying to get the note out with tweezers and pliers, but it started to rip a little bit. We didn’t want to damage it further, so regrettably had to smash the Bottle.”

As reported by Edunburgh Live, “untouched for an astonishing 7,049 weeks and four days, the message written on the mysterious parchment was finally revealed.

Signed and dated by two male workers, the message read: “James Ritchie and John Grieve laid this floor, but they did not drink the whisky. October 6th, 1887. Whoever finds this bottle may think our dust is blowing along the road.”

Intrigued to find out more about the workers, a friend of Eilidh’s conducted a bit of research and found that there were two men registered as living in the Newington area by the same names in the 1880s.

Following his incredible discovery, plumber Peter Allan, who works with Bruntsfield firm WF Wightman, told us: “It’s all a bit strange, but what a find! Where I cut the hole in the floor, is exactly where the bottle was located, which is crazy and so random.”

On Wednesday, Eilidh took to social media to share her family’s incredible find with the community.

Eilidh added: “We’ve just been amazingly lucky, and I’m glad everyone thinks it’s as interesting as we do. It feels quite nice to have a positive news story amid all this doom and gloom that’s around at the moment.

“Now, I’m thinking we need to preserve the note and replace it with a message of our own for future generations to discover.”

Responding to Eilidh’s post on the I Love Morningside page on Facebook, Lucie McAus commented: “I don’t think they ever could have predicted when they wrote it that you would be able to take a photograph using a device no bigger than your hand and put it instantly on a platform that could reach the entire community in a few seconds. Incredible.

“If you place one for the next person who knows how it would be discovered and the information shared? What a lovely timeframe from the past.”