The Discovery of the Ancient ‘City of Giants’ in Ethiopia Could Rewrite Human History

In 2017, a group of archaeologists and researchers discovered a long-forgotten city in eastern Ethiopia’s Harlaa region. It’s known as the ancient ‘City of Giants,’ which was built around the 10th century BC.

The discovery was made by an international team of archaeologists, including researchers from the University of Exeter and the Ethiopian Cultural Heritage Research and Conservation Authority.

Gigantic cities built and inhabited by giants are the subject of several stories and folklore. The traditions of several societies that were separated by great oceans all indicated that there were giants who lived on Earth, and numerous megalithic structures from different periods of history also suggest their existence.

According to Mesoamerican mythology, the Quinametzin were a race of giants tasked with erecting the mythological metropolis of Teotihuacán, which was built by the gods of the sun.

A variation on this theme can be found all over the world: huge cities, monuments, and massive structures that were impossible for normal people to construct at the time they were built, thanks to advances in science.

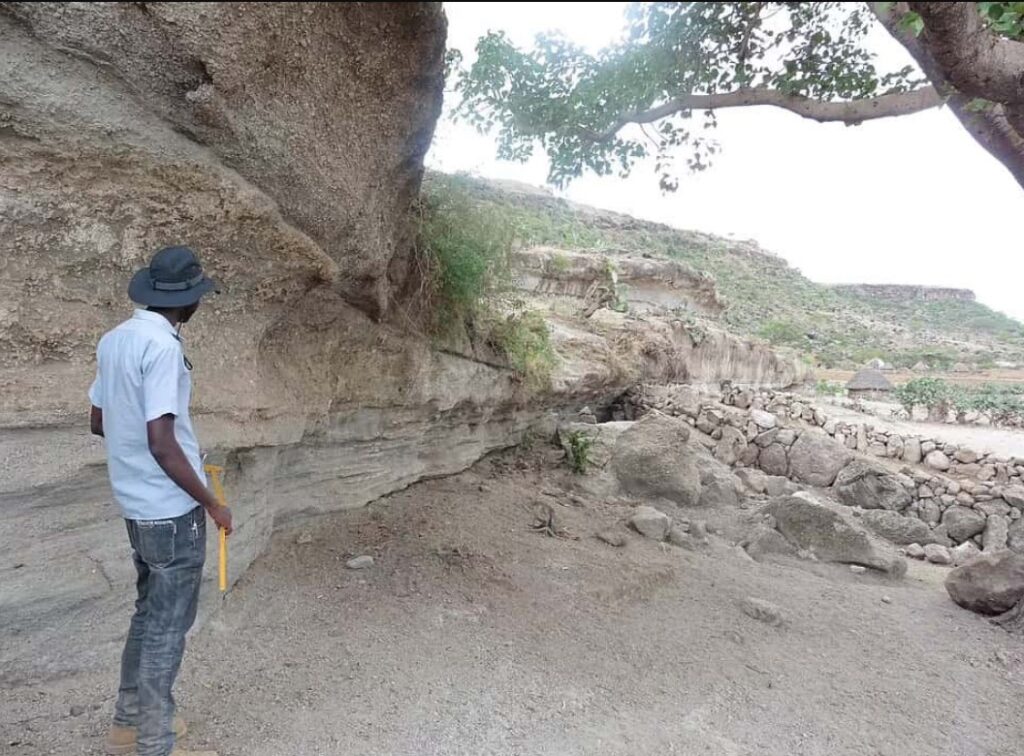

In this part of Ethiopia, that is exactly what happens. According to current residents, enormous buildings constructed of massive blocks encircled the site of Harlaa, giving rise to the popular belief that it was once home to a legendary “City of Giants.”

Locals have uncovered coins from various countries, as well as ancient ceramics, over the course of the years, they say. Also discovered were enormous building stones that could not be moved by people without the aid of modern machines.

The fact that these structures were constructed by regular humans was thought to be impossible for a long time as a result of these factors. Several notable finds were made as a result of the excavation of the archaic town.

The Lost City in Harlaa

The specialists were taken aback when they discovered antiquities from faraway regions in a surprising find. Objects from Egypt, India, and China were discovered by specialists, proving the region’s commercial capability.

A mosque from the 12th century, similar to those discovered in Tanzania, as well as an independent territory of Somaliland, a region that is still not officially recognized as a country, were also discovered by the researchers.

The discovery, according to archaeologists, demonstrates that there were historical linkages between different Islamic communities in Africa throughout that time period, and

Archeologist Timothy Insoll, a professor at the University of Exeter, who led the research said: “This discovery revolutionizes our understanding of trade in an archaeologically neglected part of Ethiopia.

What we have found shows this area was the center of trade in that region. The city was a rich, cosmopolitan center for jewelry making and pieces were then taken to be sold around the region and beyond.

Residents of Harlaa were a mixed community of foreigners and local people who traded with others in the Red Sea, Indian Ocean and possibly as far away as the Arabian Gulf.”

A City of Giants?

Residents of the Harlaa region believe that it could only have been erected by giants, according to their beliefs. Their reasoning is that the size of the stone blocks used to construct these structures could only be carried by enormous giants. It was also obvious that these were not ordinary people because of the enormous size of the buildings, as well.

Following an analysis of more than three hundred corpses discovered in the local cemetery, archaeologists discovered that the inhabitants were of middling stature, and hence were not considered giants.

Young adults and teenagers were buried in the tombs discovered, according to Insoll, who is also in charge of supervising the archaeologists working on the dig. For the time period, they were all of the ordinary height.

While acknowledging the data provided by the specialists, the indigenous people maintain that they are not convinced by their findings and maintain that only giants were capable of constructing these monumental structures. It is not the first time that modern science has dismissed a legend that has existed for hundreds of years as a mere piece of folklore.

What is it about the inhabitants that makes them so certain that the giants were responsible for the construction of the Harlaa structures? During these years, did they make any observations? It’s not like they’d have any motive to fabricate or lie about anything like that.

Despite the fact that the tombs do not provide evidence of the existence of giants, this does not rule out the possibility that the giants were involved in the building of the site.

Many believe that these beings were not buried in the same location because they are considered to be large and powerful entities. Others disagree.