The 5,000-Year-Old Pyramid City of Caral: The First City in the Americas

Seventy thousand years ago, people lived all over South America. Six thousand years ago, people began to construct cities around pyramids, in places like Mesopotamia and China.

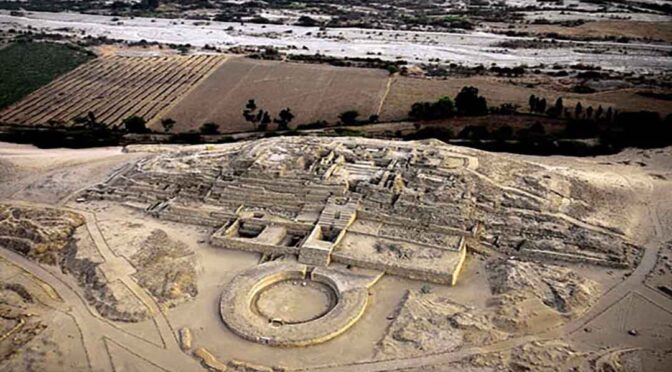

The first of these structures in the Americas, between the Andes and the Pacific Oceans, was established 5,000 years ago. Known as Caral, it was a large settlement in the Supe Valley, in what is now Peru. The point is that this gave rise to the first city in the Americas, as well as the most extraordinary archaeological site in the entire world.

Ancient cities all had a common feature, namely their access to fresh water. On the wall, across the board, this is what allowed for the irrigation that was required to form modern cities. In typical fashion, the river in the valley of Caral flowed down from the mountains to the sea.

From this, hoes were then used to dig trenches from the river to the fields. However, since the river only flows between December and April, to have water all year round, they had to build a canal that was fed by two different sources.

Along with the river water, the people of Caral made use of mountain spring water, to hydrate themselves and the plants they depended on. As a result of this, there were soon numerous fruits and vegetables, in a vast oasis, along with acres upon acres of cotton. It must have been an ancient wonder of the world.

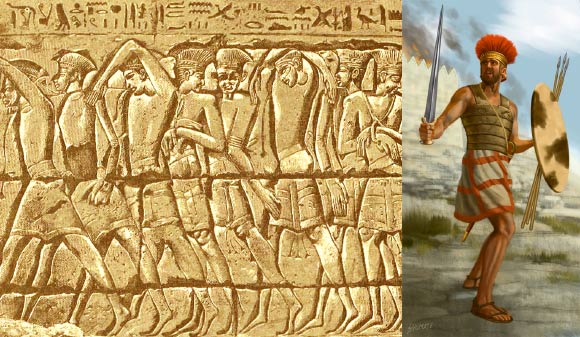

Now, although they were expert farmers, the old native Peruvians didn’t know how to fire clay. Instead, they carried things in hand-woven reed baskets. The thing that makes them the most unique, though, is the fact that the Caral-Supe civilization was a peaceful society. That is to say, citizens didn’t own weapons, unlike in almost every other civilization, both ancient and modern alike.

Their overall way of life developed out of a far greater need for welfare than that of warfare. So, the culture didn’t include aggression. Although, it is important to note that, the priests of Caral did engage in human sacrifice.

In this way, they started the tradition of burying people alive in monumental architecture, as would be seen millennia later, in cities like Teotihuacan and Cahokia, in North America. Thus, trapped souls began to serve as protectors of pyramids.

Regardless, Caral was under construction at the same time as the pyramids of Giza, in Ancient Egypt. Like all the other great cities of old, the site was simply enormous.

The temple included a 100-foot tall, multiple structures, a fire altar platform. This was also accompanied by five smaller ritual pyramids, around a central plaza, complete with an amphitheater. There was also housing for 3,000 permanent residents.

As part of this, major repairs needed to be done every two or three generations. Even though they used rather sophisticated anti-seismic methods of construction, it was still necessary to shore up monuments every few decades. They also had to deal with deadly mudslides, in the process.

Nonetheless, despite all the hardships they faced, their peaceful society not only survived, it thrived. It was all based on a complex trade network, which went to Ecuador, and even hundreds of miles away, deep in the rain forests. So, the farmers in Caral grew chili peppers and guava, among many other crops.

The most important thing they produced, though, was cotton. Manufacturers used it to make several textiles, like clothing and fishing nets. Farmers wore the former, and traded the latter to fishermen, miles away in coastal towns. In this way, people in the aristocratic city-state subsisted mainly on shellfish and dried fish, although they had a fairly diverse diet, overall.

The people of Caral brilliantly capitalized on what could have been a disaster. 5,000 years ago, climate change altered the local seascape in the Pacific Ocean.

After the temperature changed, tuna and other big fish moved on to cooler waters. Meanwhile, anchovies and sardines moved in. These new marine products were caught with nets rather than hooks and lines, as people had been doing with the larger fish. Simply put, it became easier to catch smaller fish, in far greater numbers.

In this way, the greater number of fish that were being caught, with the use of more and more nets, allowed for a greater and greater surplus, which drove the economy. This made Caral the central trading hub, in the first major marketplace in the Americas.

As the mother civilization of the New World, the Caral-Supe society set the stage for Native American civilizations, far and wide. Without even knowing how to make pottery yet, they were already expert herbalists. They chewed coca leaves with lime, to enhance the cocaine. They also painted each other with an aphrodisiac, made from the achiote plant. Then, they engaged in orgiastic religious festivals.

The natives were flute-playing lovers, not blade-wielding fighters. Everything they did was based on cooperation, not competition. This is how they lived in peace, for a millennium, from 2600 BCE to 1600 BCE. However, all good things seem to come to an end.

Unfortunately for the people of Caral, every few decades, earthquakes would routinely break up the mountains. As a consequence of this, rubble would get swept away by torrential rains. This would then wash into the river, and out into the ocean. So, after a couple of centuries, the silt built up and sealed off the flow of water.

This filled the life-giving bays with sand, which prevailing winds then blew inland. Thus, with each passing year, the dunes grew bigger and more menacing on the horizon. In the end, the once fertile fields were all reclaimed, by the inhospitable desert, once more.