Ancient DNA reveals that the Biblical Philistines originated in Europe.

A team of scientists from Germany, the United States and Korea has sequenced and analyzed DNA of 10 Bronze and Iron Age individuals from the ancient Mediterranean port city of Ashkelon, identified as ‘Philistine’ during the Iron Age.

The researchers found that a European derived ancestry was introduced in Ashkelon around the time of the Philistines’ estimated arrival, suggesting that their ancestors migrated across the Mediterranean, reaching Ashkelon by the early Iron Age.

This European genetic component was subsequently diluted by the Levantine gene pool over the succeeding centuries, suggesting intensive admixture between locals and migrants.

The Philistines are famous for their appearance in the Hebrew Bible as the enemies of the Israelites. However, ancient texts tell little about the Philistine origins other than a later memory that they came from ‘Caphtor,’ a Bronze Age name for Crete (Amos 9:7).

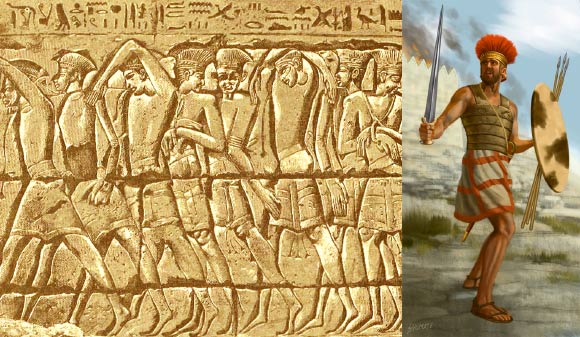

More than a century ago, egyptologists proposed that a group called the Peleset in texts of the late 12th century BCE were the same as the Biblical Philistines.

The Egyptians claimed that the Peleset traveled from ‘the islands,’ attacking what is today Cyprus and the Turkish and Syrian coasts, finally attempting to invade Egypt. These hieroglyphic inscriptions were the first indication that the search for the origins of the Philistines should be focused in the late 2nd millennium BCE.

“We found substantial changes in ways of life during the 12th century BCE which we connect to the arrival of the Philistines,” said Professor Daniel Master, an archeologist with the Wheaton Archaeology Museum and director of the Harvard Semitic Museum’s Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon, and colleagues.

“Many scholars, however, argued that these cultural changes were merely the result of trade or a local imitation of foreign styles and not the result of a substantial movement of people.”

“Our new study represents the culmination of more than 30 years of archaeological work and genetic research, concluding that the advent of the Philistines in the southern Levant involved a movement of people from the west during the Bronze to Iron Age transition.”

The researchers successfully recovered genomic data from the remains of 10 individuals who lived in Ashkelon during the Bronze and Iron Age.

They then compared DNA of the Bronze and Iron Age people of Ashkelon to determine how they were related.

They found that individuals across all time periods derived most of their ancestry from the local Levantine gene pool, but that individuals who lived in early Iron Age Ashkelon had a European derived ancestral component that was not present in their Bronze Age predecessors.

“This genetic distinction is due to European-related gene flow introduced in Ashkelon during either the end of the Bronze Age or the beginning of the Iron Age,” said Dr. Michal Feldman, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

“This timing is in accord with estimates of the Philistines arrival to the coast of the Levant, based on archaeological and textual records.”

“While our modeling suggests a southern European gene pool as a plausible source, future sampling could identify more precisely the populations introducing the European-related component to Ashkelon.”

In analyzing later Iron Age individuals from Ashkelon, the researchers found that the European related component could no longer be traced.

“Within no more than two centuries, this genetic footprint introduced during the early Iron Age is no longer detectable and seems to be diluted by a local Levantine related gene pool,” said Dr. Choongwon Jeong, also from the Max Planck Institute of the Science of Human History.

“While, according to ancient texts, the people of Ashkelon in the first millennium BCE remained ‘Philistines’ to their neighbors, the distinctiveness of their genetic makeup was no longer clear, perhaps due to intermarriage with Levantine groups around them,” Professor Master said.

“These data begin to fill a temporal gap in the genetic map of the southern Levant.

At the same time, by the zoomed-in comparative analysis of the Ashkelon genetic time transect, we find that the unique cultural features in the early Iron Age are mirrored by a distinct genetic composition of the early Iron Age people,” said Dr. Johannes Krause, also from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.