5,000-Year-Old Deer Carvings Discovered In A First for Scotland!

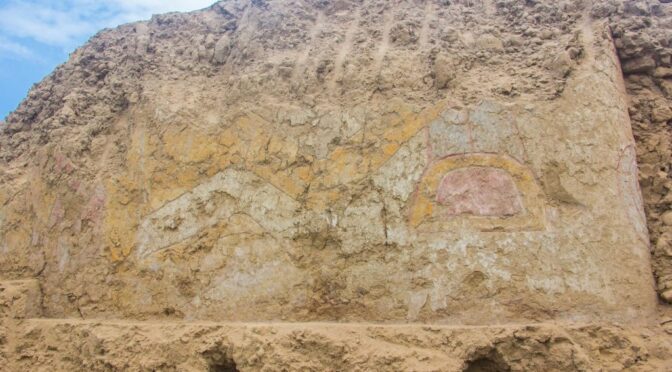

Lost for around 5,000 years, an amateur archaeologist has discovered deer carvings inside Kilmartin Glen’s Dunchraigaig Cairn in the west of Scotland. The Neolithic or Early Bronze Age carvings depict two male red deer with fully-grown antlers.

Two other deer carvings were also found, along with another engraving of an unidentified creature. Dr. Tertia Barnett, Principal Investigator for Scotland’s Rock Art Project at Historic Environment Scotland (HES) explained that until now it was thought that prehistoric animal carvings of this date “didn’t exist in Scotland.”

Questing the Cups, Quizzing the Deer

The carvings were recently discovered inside Dunchraigaig Cairn by Hamish Fenton, an archaeology enthusiast visiting the area, who found the faint marks etched on the capstone of an Early Bronze Age burial cist .

HES explained that the illustrations represent “the first time that animal carvings of this date have been discovered in this area,” which was until now famous for its cup and ring marked stones .

The cairn measures 30 meters (98.4 ft) wide and includes three stone burial chambers, or cists. The deer were discovered carved in the third cist.

In an article published on the HES website, the archaeologists say the cist was “dug directly into the ground, lined with drystone cobbled walls and capped with an unusually large stone over 3.5 m (11.48 ft) long.”

The cairn was erected amidst a deeply-sacred landscape that was until now defined by cup and ring marked stones . The greatest mystery here is “why,” or maybe “how,” these two different art forms came to be used at one location, unlike any seen anywhere else at Neolithic and Early Bronze Age sites in the United Kingdom.

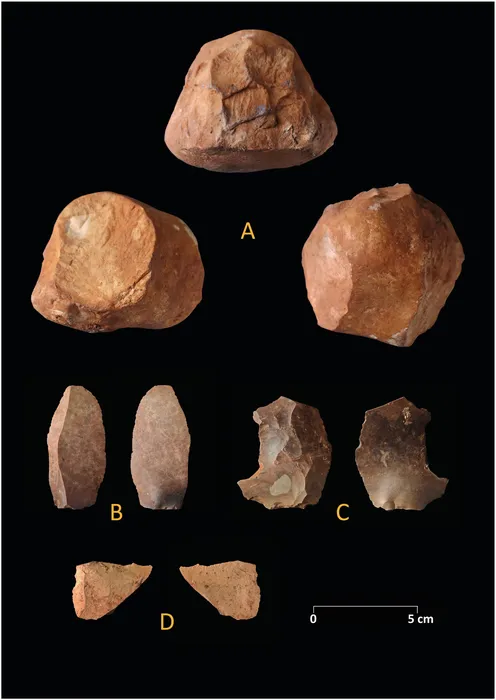

Cup and ring marked stones are composed of a central cup mark surrounded by pecked concentric circles. The original function or purpose of the stones has been a subject of much debate.

Many historians read them like star charts, while others maintain they are local maps. In the north of Scotland, where I am from, we tell folk that the cups were filled with oil and lit so that ships at sea, overland traders and shepherds could have safe passage at night.

You could almost say cup and ring marked stones are “ten a penny” in comparison to the recent extremely rare discovery of deer carvings.

In fact, so unexpected was this set of carvings that their emergence “completely changes the assumption that prehistoric rock art in Britain was mainly geometric and non-figurative,” explained the HES article when discussing the find.

“This was a completely amazing and unexpected find and, to me, discoveries like this are the real treasure of archaeology, helping to reshape our understanding of the past,” highlighted Fenton in the Independent.

Digital Technology Peers 5,000 Years Back in Time

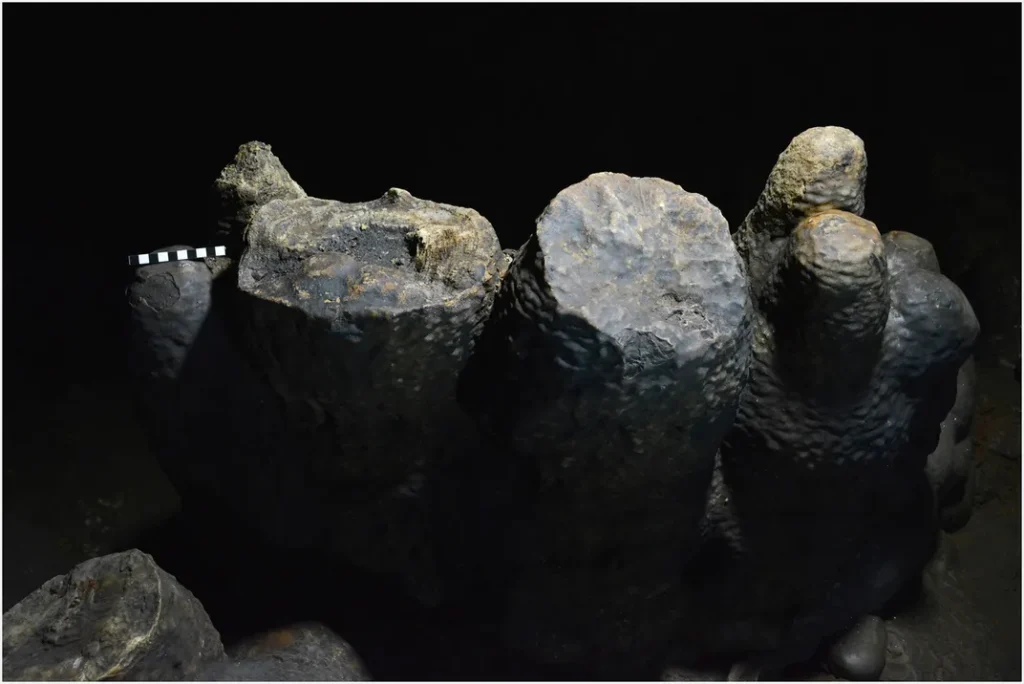

The reason the carved deer have gone unnoticed for 5,000 years is because there is almost nothing for the human eye to see. Hamish suspected the lines might represent something.

His intuition was only ascertained after a structured light scan was carried out by HES digital documentation experts. A detailed 3D model with photographic textures revealed anatomical detail that was way beyond the capabilities of the human eye.

Dr. Barnett has concluded that “ digital technology is becoming increasingly important for archaeology, and particularly for rock art, and is a key to unlocking the hidden secrets of our past.”

As part of Scotland’s Rock Art Project, HES have now recreated “1,000 3D models of prehistoric rock art which are now available online for people to explore.”

Realigning the History of the Kilmartin Valley

What is being regarded as the most remarkable aspect of the carved deer at Dunchraigaig Cairn is the high level of anatomical detail, according to Dr. Barnett. But don’t for a moment think this was achieved because hunters gazed at their prey while it roasted over a glowing cave fire.

The anatomical detail results from the fact that our ancestors were most often up to their elbows in torn animal carcasses. Through repeatedly chopping, carving, slicing and stripping, ancient hunters became highly tuned to how the muscles and bones of deer worked, and this knowledge was projected into their rock art .

HES are most interested in the fact that Neolithic communities in Scotland carved animals as well as cup and ring motifs. While to find both types of art together is relatively common at Scandinavia and Iberia Neolithic sites, until now, none were known of in Britain.

With both types of carvings present at Kilmartin Glen, big questions arise pertaining to the relationship between these distinct types of carving and their significance to the people that created them.