Viking Ring Found in Polish Stronghold is Actually Rare Christian Artifact

What was thought to be a Viking ring has turned out to be something else entirely. Even highly-trained professionals sometimes see what they expect to see, instead of what’s actually there, at least for a little while.

That’s what the Science in Poland website reported in November, when talking about an unusual historical find. The find in question was a medieval ring that dates from the ninth or tenth century.

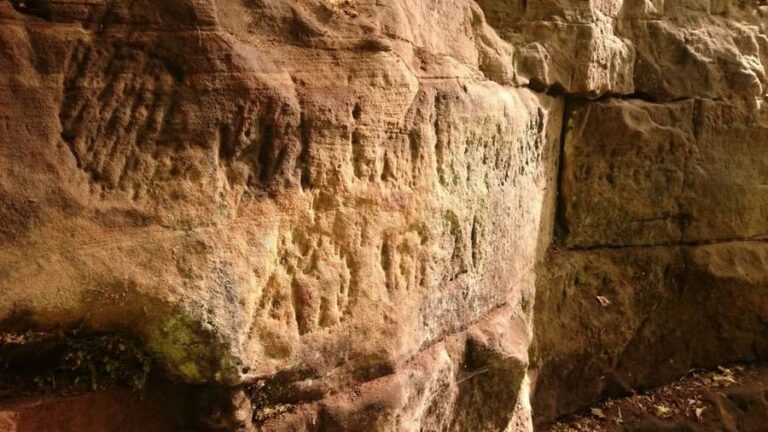

The ring was originally found in 2003 by Mirosław and Małgorzata Andrałojć together with archaeologist Mariusz Tuszyński, who at the time was head of research work in Grzybowo.

It was found using a metal detector, and was located in a stronghold in Grzybowo, Poland, near a spot where archaeologists had already found a sizable quantity of medieval coins.

When it was first discovered, the team thought it was of Viking make, because it was covered with a tight, dense, weave depicting animals.

Archaeologist Miroslaw Andralojc said that the design first led them to believe it was a Scandinavian object, but after doing a more complete analysis, they realized that the design was more consistent with similar objects from the Carolingians of Western Europe.

He speculated that it may have been made in the Eastern Alps, where Christianity was already well-established by the eighth century. Hence the surprise that occured when they realized they most likely had a Christian artifact on their hands instead of pagan Viking one.

The ring was made of lead brass, which the wealthy of the era valued because it had more of a true golden color than metals like bronze, which means that the ring probably belonged to a person of high status. It was also interesting for its shape; the ring’s interior wasn’t truly round.

Instead, it was shaped in a way that it conformed better to the shape of a human finger and would be less likely to slide off by accident. In order to put it on or take it off, it would have to be rotated 45 degrees one direction or the other, which was the only way it would move freely on or off.

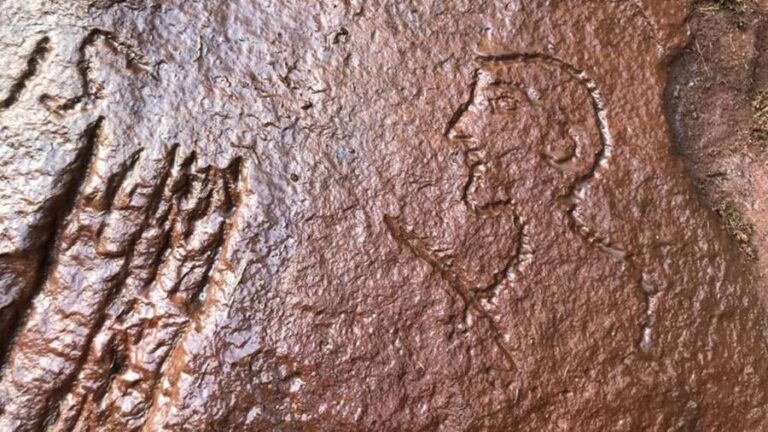

The exterior design of the jewelry showed overlapping images of birds, and a crown wound with flowers. The floral winding was in the shape of a medallion, which, in turn, shows the figure of an animal lying down. A similar design had previously been found on a Carolingian brooch held by the British Museum.

Andralojc stated that his team believes the design to show the Agnus Dei, the Lamb of God, surrounded by peacocks. This would be Christian symbolism, since peacocks were considered a symbol of resurrection. Researchers have also seen similar styles of decorative weave on decorative candlesticks at an Abbey in Upper Austria.

The discovery of the “Viking” Christina ring does raise real questions about how it got where it was found. The stronghold existed from the 920s until the middle of the eleventh century, which does encompass the period during which the ring was made, but how did it end up so far from home?

As yet, the researchers have no clear theory about whether the ring was loot, a gift, or proof that the owner belonged to a Christian community.

The Carolingian dynasty or empire was a group of rulers who eventually became the kings of the Franks around 750 AD and ruled for about 150 years. The most generally well-known member of this dynasty was Charlemagne.

They dynasty is thought to have been founded by Arnulf, Bishop of Metz, early in the seventh century, and during its peak, leaders of this dynasty ruled over much of Central and Western Europe, Before coming into its full power,, the early members of the dynasty held the mayoralty of the palace of Austrasia, which covered what is now the Northeastern part of France, Belgium, and central Germany.

Charlemagne became King of the Franks in 768, and was anointed Emperor by Pope Leo III in 800 AD. Making Charlemagne Emperor was a win-win for both the dynasty and the Catholic Church, the Church legitimized the Empire’s rule, and the Empire offered help to the Church in terms of military support.