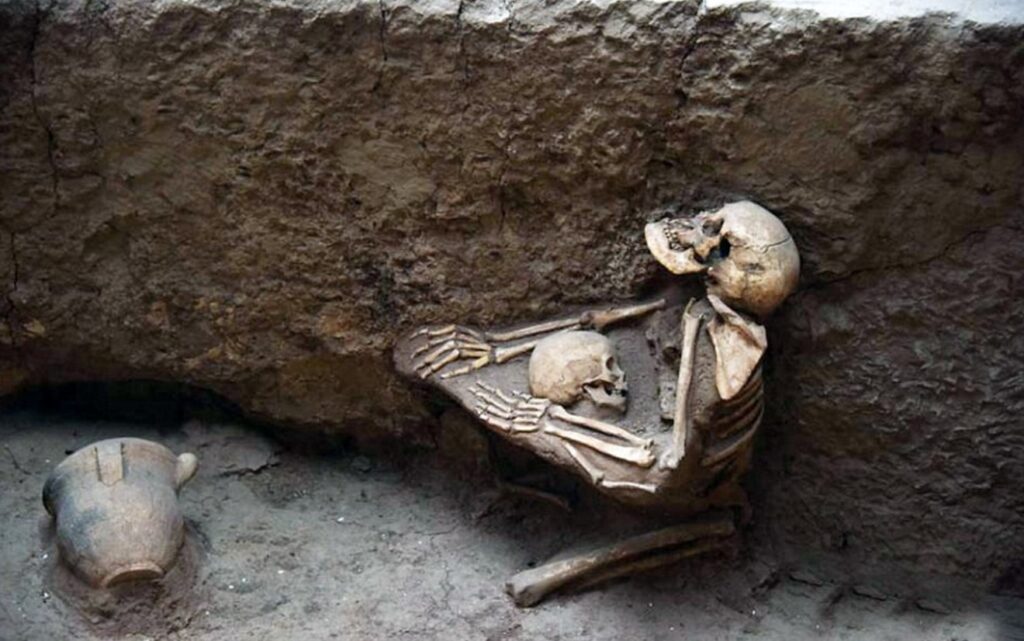

4,000-year-old skeletons of a mother and her child embrace

Victims of an ancient earthquake that had once struck the Chinese community of Lajia are now on display at the Lajia Ruins Museum.

The ruins of Lajia are in Qinghai Province in Northwest China, near the Upper Yellow River. China People’s Daily has said that the site is bringing people to tears; victims are shown to be huddling together in what were their final moments. One display shows women embracing their children in an attempt to protect them.

This scene is reminiscent of the victims of the Roman city Pompeii, which was destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD.

One difference is that the Pompeiian people are shown with such humanity because they have been preserved by volcanic ash and mud, while the skeletal remains at Lajia inspire horror.

An earthquake shook the ground around them, triggering a mudslide that came down and demolished a Bronze Age building that the people had taken cover in.

The building was a family home that the people ran into thinking they would be safe. On one of the walls preserved for all of the eternity is a woman embracing her child, her skull looking upwards as she caresses the child in her arms.

The remains of two children clinging to an adult lie against another wall. Upstairs, you will find another woman and child in almost the same position as the first two. These people are from the Bronze Age Qijia culture, their remains date back to around 2,000 BC, making them 4,000 years old.

Earlier this year the remains of a child clinging to his mother were displayed in Pompeii. There are no skeletons in Pompeii – the ancient mud and ash saw to that.

Pompeii was destroyed by a pyroclastic flow: an extremely fast-moving cloud of rock and hot gas that can move at speeds of 450 miles an hour. Given these speeds, it is instantaneous death for those that chose to ignore the warnings given by Vesuvius.

It hugs the ground while it moves and spreads laterally, consisting of two parts: a hot ash plume that hovers above and the basal flow that consists of heavy rocks.

The ash plume incinerates anything it touches while the basal flow destroys anything in its path. Herculaneum was also devastated when Vesuvius exploded.

It is unknown how many died when Vesuvius exploded but it is estimated to be between 10,000 and 25,000. Many victims perished at the city port while trying to take cover in warehouses that were near the dock.

Others tried to get to the last remaining boats while others ran for their homes, most likely then praying to their household gods.

The mother and child were discovered in what archaeologists call the House of the Golden Bracelet. The home of a wealthy family, the walls covered in frescoes and also contained a large garden. It was all carbonized when the 300 degree cloud hit.

“Even though it happened 2000 years ago, it could be a boy, a mother, or a family,” said Stefania Giudice of Naples National Archaeological Museum. “It’s not just archaeology; it’s human archaeology.”

Now branded as the “Pompeii of the East,” the poor town of Lajia is now one of the most important archaeology sites in China.

Mirrors, oracle bones, and stone knives are just a few of the artifacts found at the site.

The victims of Lajia were first found in 2000 in a loess cave, one of many in the settlement that consisted of caves and houses.