Roman Mosaic Found Under Street of Hvar in Croatia

In the Old Town on the Adriatic island of Hvar, Croatia, a Roman mosaic was unearthed beneath a narrow street. The elaborate geometric mosaic floor dates to the 2nd century A.D. and was part of a luxurious Roman villa Urbana.

The site was uncovered in 1923 to construct a canal for rainfall drainage, and the villa’s remnants were discovered two feet below street level.

To safeguard the findings from water intrusion, they were finally covered with slabs and reburied.

The installation of the water drainage system was not completed after the 1923 excavation and increasing problems with penetration from ambient moisture and rising sea levels threaten the survival of the ancient remains of Roman Pharia in Hvar’s historic Old Town.

Residents would like to see the mosaic remain in situ, covered with plexiglass so it can be protected and enjoyed at the same time, but the sea has risen by a foot and a half since the mosaic was created and the street is no longer dry land.

The new water pipe installation is still happening too, and they will be just a few inches above the mosaic.

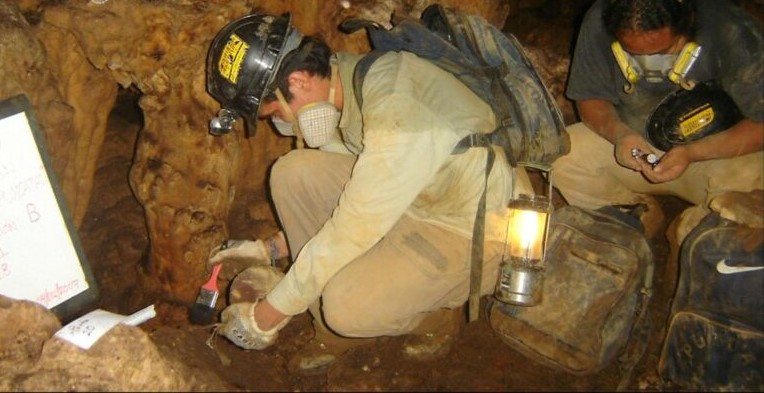

Work on the opening of the mosaic is carried out on behalf of the Old Town Museum by Dr. Sara Popović and archaeologist Andrea Devlahović.

Archaeologists are presently digging 14 additional sites near the mosaic site in search of further fragments from the villa Urbana, other mosaics, and any archaeological evidence that might identify the structure, or at the very least characterize it as a public or private facility. Officials will have a clearer sense of what to do next after the excavations are finished.

The Museum of the Old Town’s archaeologists has recommended raising the mosaic and transporting it to the museum for long-term conservation and future exhibition.

They’ll replace it with a replica that can be walked on without damage. That proposed solution has to be approved by conservators and heritage officials from Split.

The island was conquered by Rome in the 3rd century BC. Pharos became Pharia, the plain was renamed Ager Pharensis.

At the beginning of the 8th century, the island was penetrated by the Slavs, who took the ancient name for the town and island – Hvar.

The name of Hvar Island comes from the ancient names for today’s Stari Grad – Pharos and Pharia. In the Middle Ages, the name was slavicized to Huarra. With the relocation of the diocese, the name also moved and the old seat became Stari Hvar, and then Stari Grad.

The historic town center of Stari Grad and the cultural landscape of the Stari Grad Plain was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2008.