Archeologists of Egypt Discover Pharaoh’s Boat in Perfect Condition

Archeologists of Egypt uncovered a boat claimed to have been “perfectly preserved” by Pharaoh Khufu himself, which led to verified theories of how ancient civilization constructed their wonders.

Probably the most famous and well-known of Egypt’s many ancient landmarks and includes the Great Pyramid of Giza, the Pyramid of Khafre, and the Pyramid of Menkaure, along with their associated pyramid complexes and the Great Sphinx of Giza.

The Great Pyramid of Giza, or the Pyramid of Khufu, is a spectacle of the three still existing pyramids today, who marvel at how a society over 4,500 years ago managed to build such a colossal structure.

But archeologists were able to slowly combine what this ancient civilization looked like and how ingenious and brilliant people have worked together, thanks to a find made more than half a century ago.

Amazon Prime’s “Secrets of Archaeology revealed some of those secrets. The 2014 series explained: “On this plateau, set on the edge of the desert, the story of the pyramids achieved its finest hour.

“It is here that we best appreciate the grandeur and majesty of these constructions, and the organizational skills and methods used to erect them.

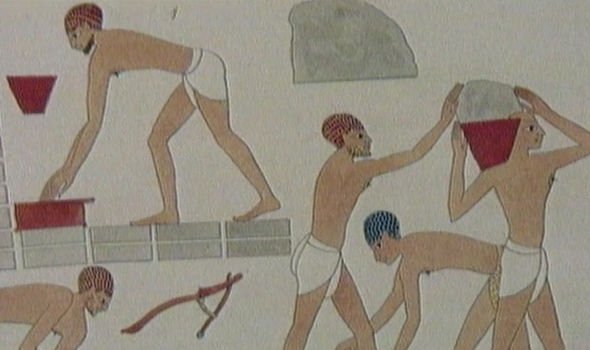

“The workers here were organized into teams that hauled blocks of stones on huge sledges mounted on logs of wood. “Each team was made up of about 1,000 men organized along military lines and led by a master mason and various underlings.

“They were not slaves, they earned a regular wage, bed, and board and it is thanks to their work that these immense structures were ever completed.”

The series continued, explaining the clever tactics used by the ancient society to haul together in the building process. It added: “Even today, such imposing buildings would involve complex engineering problems.

“The Great Pyramid of Cheops, which was the first one to be built in Giza around 2500BC, has a base that covers over 12 acres (48,500 square meters). “More than 2,300,000 blocks of stone were needed to build the base and weighed between two and 200 tonnes each.

“It may sound incredible, but this was once a lush green land, with neither desert nor buildings. “Irrigation canals linked the areas to the Nile, and some of the stones used in buildings were transported on these canals.”

The documentary went on to reveal how evidence of this was discovered more than 50 years ago. It added: “A boat made with cedarwood built almost 5,000 years ago was discovered here in 1954 near the Pyramid of Cheops, still in a perfect state of preservation.

“Archaeologists found it belonged to the pharaoh Cheops himself, 140 feet long, equipped with 12 oars and was probably used by Cheops when he traveled along the Nile. “On those occasions, his subjects could get a glimpse of their Pharaoh and pay homage to him.”

At completion, the Great Pyramid was surfaced with white “casing stones” — slant-faced, but flat-topped, blocks of highly polished white limestone.

However, in 1303, a massive earthquake loosened many of the outer casing stones, which were taken away 50 years later to be used in the building of mosques and fortresses in Cairo.

Many other theories have been proposed regarding the pyramid’s construction techniques, disagreeing on whether the blocks were dragged, lifted, or even rolled into place.

The Greeks believed that slave labor was used, but modern discoveries made at nearby workers’ camps associated with construction at Giza suggest it was built instead of thousands of skilled workers.

Czech archaeologist, Miroslav Verner, claimed that the labor was organized into a hierarchy, consisting of two gangs of 100,000 men, divided into five zaa or phyle of 20,000 men each, which may have been further divided according to the skills of the workers.