50,000-Year-Old Tiara Made from Woolly Mammoth Ivory Found in Denisova Cave

Archaeologists recently discovered the remains of an ancient tiara that was worn by a man. The question now is whether the head crown was meant to mark its wearer’s royalty — or simply hold back his hair.

The ivory tiara turned up this summer in the Denisova Cave in the Altai mountains of Siberia. The artifact, made from the tusks of the now-extinct woolly mammoth, is between 35,000 and 50,000 years old — likely the oldest one found in the North Eurasia area to date.

The findings, first reported by The Siberian Times, haven’t yet been published in a scientific journal, but the authors plan to submit their report for publication next year.

Tiaras or headbands “made from bone, antler or mammoth tusks are one of the rarest types of personal ornaments known in the Upper Paleolithic of Northern Eurasia,” said Alexander Fedorchenko, a junior researcher at the Department of Stone Age Archaeology at the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

The Upper Paleolithic, or the end years of the Stone Age, began about 40,000 years ago. In addition to mammoth ivory, the items found in the cave from this time period were made up of a variety of raw materials, like soft stones, tubular bones of animals and birds, mammal teeth and shells from freshwater clams and ostrich eggs, Fedorchenko told Live Science.

“On the one hand, we were very surprised to find this unique diadem,” Fedorchenko said. “On the other hand — when you work at Denisova Cave, you need to be ready for any, even the loudest, scientific discoveries.”

The Denisova cave is famous for first revealing the remains of an extinct human lineage called the Denisovans. The tiara turned up in the same layer of the southern chamber of the cave where those first remains, such as a 40,000-year-old adult tooth was found.

Even though no other remains from other human lineages have been excavated in that layer of the Southern Chamber, Fedorchenko said they can only guess if the head piece belonged to a Denisovan.

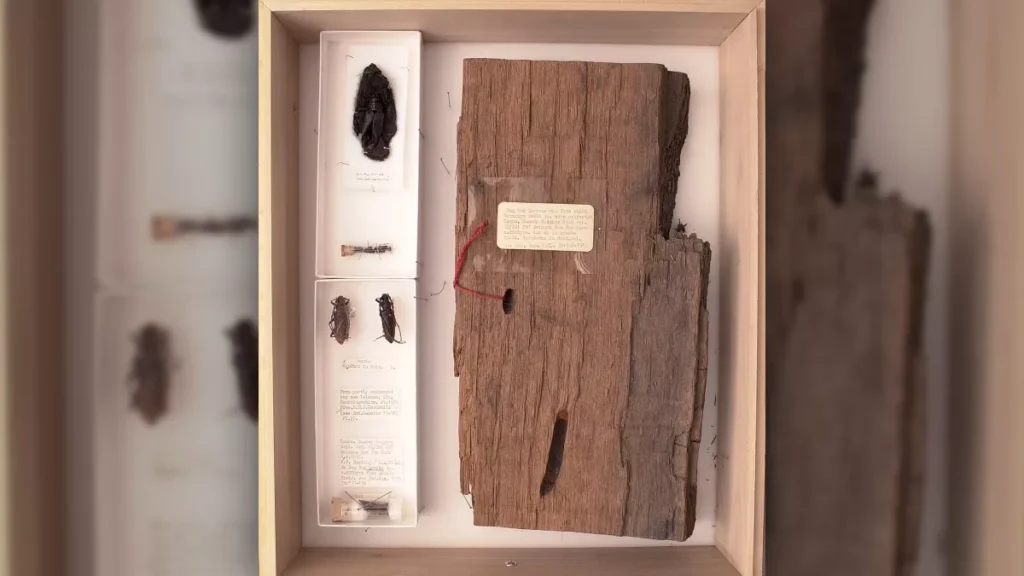

Making of a tiara

The Paleolithic dwellers of the cave would have needed to take several steps to craft this diadem, Fedorchenko said. After freeing the mammoth tusks, they likely cut them into thin pieces and soaked them in water so that they could be bent into shape. They then processed them by shaping, scraping, cutting, grinding, drilling and polishing the ivory, Fedorchenko said.

If it’s anything like other tiaras from this time period found in the East European Plain and Eastern Siberia, it most likely had drilled holes at the end to attach it to the head with some sort of cord or strap, he added. Indeed, the largest fragment they found — one of three that together made up a third of the full piece — had half a hole on one side.

Though not seen on this fragment, the outsides of such tiaras are also often decorated with engravings or “complex ornaments,” Fedorchenko said.

Typically, tiara remains come in several pieces, making it difficult for scientists to know for sure if they came from an actual tiara, Fedorchenko said. However, in this case, “we can judge relatively confidently” that the new find is a tiara.

First of all, the length of the biggest fragment — 5.9 inches (15 centimeters) — is too long to be a bracelet. Second, the tiara has a bend that’s shaped to fit the temple of an adult man.

“If we assume that the part of the tiara that was not found so far continued to bend at the same angle as the preserved one, the dimensions of this product would be very suitable for a man with a relatively large head,” Fedorchenko said.

Finally, when they observed the find under a microscope, they found “use-wear traces” such as scratches, microscopic traces of damage, abrasion marks and polishing that would have happened because of contact with organic material, like skin.

They don’t know if this diadem was a mark of something “special,” like royalty, or just an everyday headband to keep the hair back. But most diadems that are found at archaeological sites in Siberia and Europe are often marked with lines, dots and zigzags, which “indicate the special role of these objects in the culture of Upper Palaeolithic people,” Fedorchenko said.

Perhaps, it could have also been a mark of a family or tribe, Fedorchenko said.

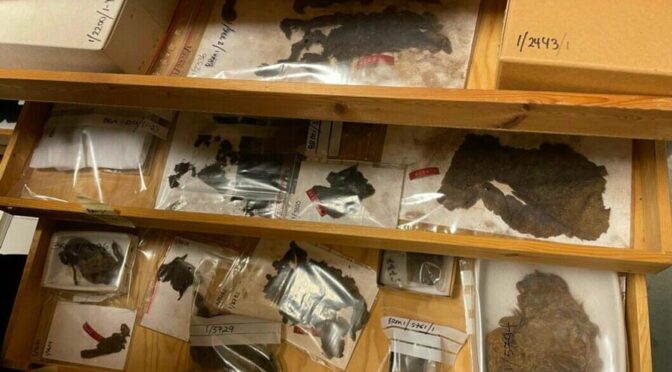

This year, the team also found other interesting artifacts in the Denisova Cave, such as an ivory ring, a bone needle and beads. “Together with the diadem, these new artifacts will allow us to more completely reconstruct the peculiarities of the life of the Upper Paleolithic inhabitants of the Denisova Cave,” he said.