Oldest Ever Neanderthal Remains Found, Dating Back 116,000 Years!

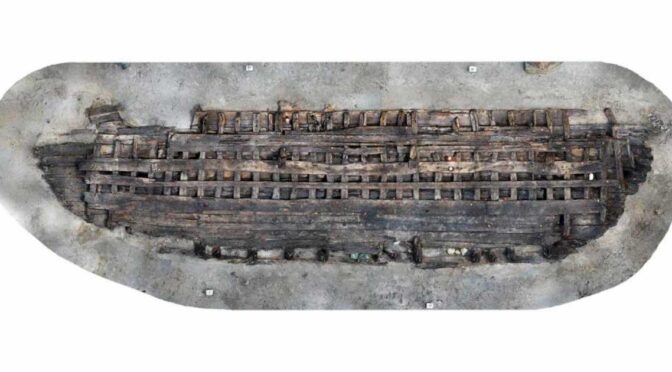

In 2008 a team of archaeological excavators digging in the Stajnia Cave near Mirów in Poland, unearthed deeply-ancient tools among the remains of Neanderthal hunters. This discovery represented the first Neanderthal remains ever discovered in Poland.

However, a recent shift in the scientific molecular clock indicates that these discoveries are not “55,000 years old,” as was believed, but they are in fact “the oldest remains of Neanderthals in Central Europe,” possibly dating back as far as 116,000 years.

Doubling Dates in a Heartbeat

When conducting the fieldwork directed by Mikolaj Urbanowski, the archaeologists at Stajnia Cave located north of the Carpathians in Poland discovered a Neanderthal molar in 2007.

At the time, scientists extracted its mitochondrial DNA and dated it to somewhere between 42 and 52 thousand years old. Now, a new study published in the journal Nature demonstrates how this ancient tooth is much older, twice as old in fact.

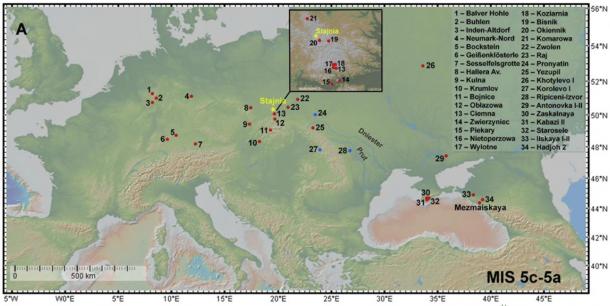

The new research was conducted by a international team of scientists from the University of Wrocław, the Polish Academy of Sciences and the Polish Geological Institute , who together analyzed the Neanderthal DNA gathered from the Stajnia Cave tooth sample, comparing it with DNA samples found in other caves, such as Scladina Cave in Belgium and Hohlenstein-Stadel Cave in Germany.

The Stajnia Cave DNA was found to be more closely related to the North Caucasus population than with that of Western Europe, which according to the researchers was hard evidence of the “mobility of Neanderthals.”

Furthermore, this new DNA research showed that the Stajnia Cave molar was far older than other Central European Neanderthal remains, and having been recovered in a “Micoquian context” it has been re-dated to “approximately 80,000 – 116,000 years old.” Yup, you read that right. These remains could possibly be “116 thousand years old,” which makes it the oldest Neanderthal remains ever discovered in Central Europe.

Descending Ice Giants: Migration Caused by Climate Change

The initial dates given to the Neanderthal molar, and associated remains and tool, was “approximately 52-42 thousand years ago,” but this new study has now proposed that they date back to around 116 thousand years ago.

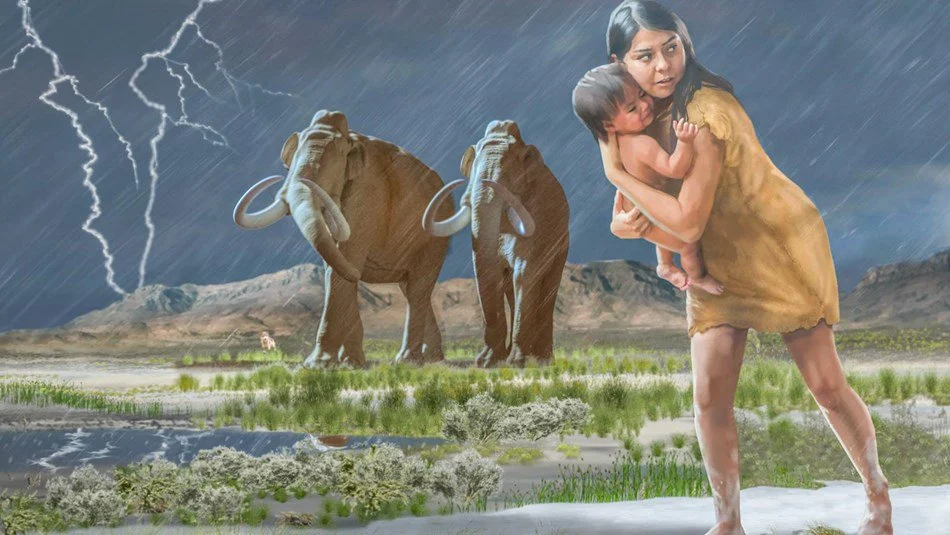

At this time, according to an article on PHYS, the climate changed abruptly and caused the Central-Eastern European environment to shift from forested, to open steppe and taiga habitat. These changes also caused the southward dispersal of Arctic wooly mammoths and wooly rhinos .

During this time of great ecological shifts, known to geologists as the “Micoquian,” bifacial stone tools emerged in Central-Eastern Europe across eastern France, Poland and the Caucasus.

These tools were slowly developed until the demise of the Neanderthals. Professor Mateja Hajdinjak, a post-doctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and co-author of the paper published in Nature, said the team used “the molecular genetic clock” to place the fossilized tooth at the beginning of the Last Glacial , when the site could have been “a logistical location settled during forays into the Krakow-Czestochowa Upland.”

A Thrilling Breakthrough: The Oldest Neanderthal Remains in Central Europe

Scientists generally tend to be ultra-careful when describing any emotional responses to big discoveries, and rightfully so, for there should be no room for such subjective vagaries in logical processes.

But on this occasion, Wioletta Nowaczewska of Wroclaw University, a co-author of the paper, said the team were “thrilled” when the results of their genetic analysis revealed the tooth was “at least 80,000 years old” and maybe even 116,000 years old.

Exemplifying how rare this Neanderthal molar discovered in Poland is within a European context, a July 2016 paper published in Science Daily by a team of scientists from the University of Cologne explains that in Germany there are only “four known settlement sites for the time period between 110,000 to 70,000 years ago.”

Meanwhile, there are “ninety-four” sites dated between 70,000 to 43,000 years ago, with most dating to the later date around the time the Neanderthals disappeared.

The Molecular Clock and Archaeological Paradigm Shifts

Precisely why the Neanderthal species died out is still unclear and it continues to be a hot topic for debate within the scientific community who are currently split between several contrasting models demonstrating how their extinction came about.

In the last decade several papers from leading institutions have claimed: low genetic diversity , decreases in fertility , the rise of Homo sapiens and the current favorite is climate change. All of these, and more, have all been blamed for having bought about the demise of the Neanderthals.

At a molecular level, the tools and human remains discovered in Stajnia Cave are very similar to those discovered at sites in Germany, Crimea, Northern Caucasus and Altai.

This is presented in the new study as further evidence of “increasing mobility” among Neanderthal groups who hunted across the Northern and Eastern European plains, stalking slow moving “cold adapted migratory animals,” according to the scientists.

Thanks to the shift in the molecular clock, this increased mobility has now been identified as having occurred around 100,000 years ago, which is double the previously accepted dates of occupation at Stajnia Cave. What else could the molecular clock technique reveal about our ancient origins?