Scientists Begin Unveiling the Secrets of the Mummies in the Alexandria ‘Dark Sarcophagus’

The massives stone coffin found in July contains a woman and two men, including one who survived brain surgery

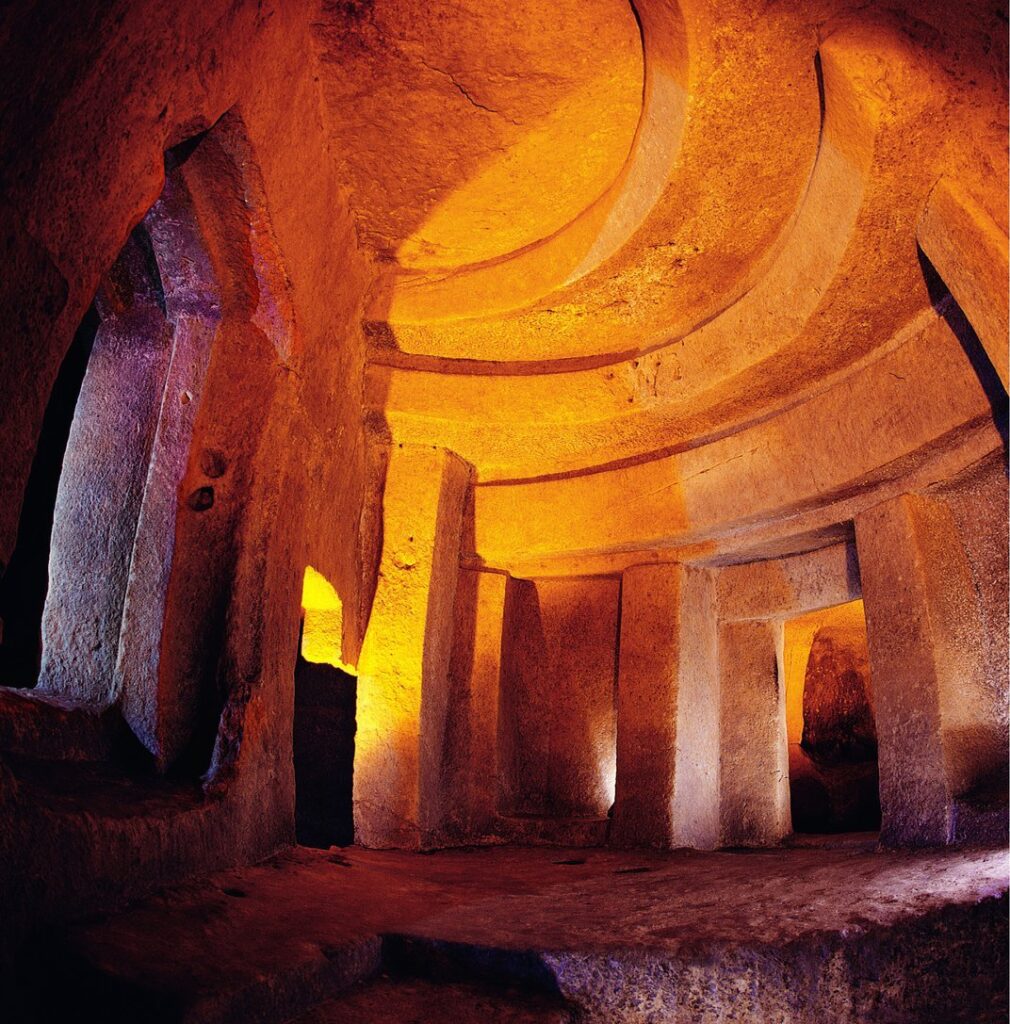

In , archaeologists in Egypt revealed that they had found something creepily interesting in the city of Alexandria: a massive 30-ton, black granite sarcophagus.

Discovered on a building site, it was the largest stone coffin ever found in the city. Internet speculation ran wild, with people suggesting it was cursed, that opening it could lead to the end of the world, or that the massive 8.5-by-5-foot tomb contained a super-mummy.

Many were disappointed that when the coffin was opened it revealed three normal human bodies floating in a soup of red sewage (though it did spark a petition asking Egyptian authorities to let people drink the red liquid from the dark sarcophagus in order to “assume its powers”).

Now that the hoopla has died down, researchers have revealed the initial results of their scientific analysis. While it’s not as exciting as finding Alexander the Great, the residents of the tomb still offer interesting insights.

Nevine El-Aref at Ahram Online reports that a team of researchers led by Zeinab Hashish, director of the Department of Skeleton Remains Studies at the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities, analyzed the skulls, pelvises and other bones.

The bodies include one woman and two men who appear to have been deposited at different times and stacked on top of one another. The fact that a woman is included in the burial overturns an earlier hypothesis that the tomb’s inhabitants were soldiers.

The age for the woman was between 20 and 25; for one of the men, between 35 and 39; and the other man, between 40 and 44. That last skeleton has a hole in its skull, which healed long before the man died.

“This means that the cavity might be a result of a trepanation,” Hashish tells El-Aref. “This surgery is the oldest surgical intervention ever known since pre-history, but was rare in Egypt,” Hashish adds in a statement.

The remains are believed to date either to Egypt’s Ptolemaic period, 332 to 30 B.C., when it was ruled by a Greek dynasty, or the Roman period, when it was under the control of that empire, from 30 B.C. to 642 A.D.

Trepanation was a surgical procedure practiced throughout the ancient world, from South America to Africa and Asia, and it continued being practiced into the 16th century in some places.

The surgery involved cutting a hole into the skull for religious reasons or as a medical intervention—to relieve headaches, swelling of the brain and hypertension. There are only a handful of examples from Egypt, which makes this find special, although it’s impossible to know why this particular person received the treatment.

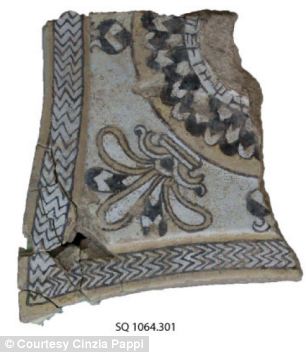

Bones weren’t the only item found in the coffin. Researchers also found a small gold artifact and three thin sheets of gold, each square embossed with an image.

Owen Jarus at LiveScience reports that one of the images may represent the seed pod of an opium poppy inside a shrine, which may have associations with death, sleep and rebirth. Another shows an unhooded snake with its mouth open, which could be a symbol of the goddess Isis and represent rebirth.

“As a rule of thumb, it would seem that snake jewelry was primarily a female thing,” Jack Ogden, the president of the Society of Jewellery Historians tells Jarus. “But I am not sure whether one could suggest that the presence of a snake here suggests it was connected with the female occupant of the sarcophagus.”

The third gold panel shows either a palm branch or a stalk of grain, both of which are related to fertility and rebirth.

The Ministry also weighed in on the disgusting red necro-Kool-Aid found in the sarcophagus, confirming that it is likely sewage water that infiltrated the coffin and mixed with decomposed mummy wrappings, though they plan to analyze the stuff more closely to figure out exactly what it’s made of.

The team also plans to continue studying the bones, using DNA tests to figure out whether the people inside the sarcophagus were related to one another. They will also use CT scans to learn more about the bones themselves. Even if those scans are successful, it leaves one big question out there—why were these bodies buried in such a huge, black sarcophagus?

It also seems the danger of the sarcophagus unleashing a curse upon the world has passed, since the coffin has been open for over a month and most of us are still around.

“I was the first to put my whole head inside the sarcophagus… and here I stand before you … I am fine,” Mostafa Waziri, secretary-general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities told reporters after opening it in July. “We’ve opened it and, thank God, the world has not fallen into darkness.”