Well-Preserved Iron Age Butter Found At The Bottom Of Lake In Scotland

Now, the wooden butter dish remains one of the most evocative items left behind by Scotland’s ancient water dwellers who made their homes on Loch Tay.

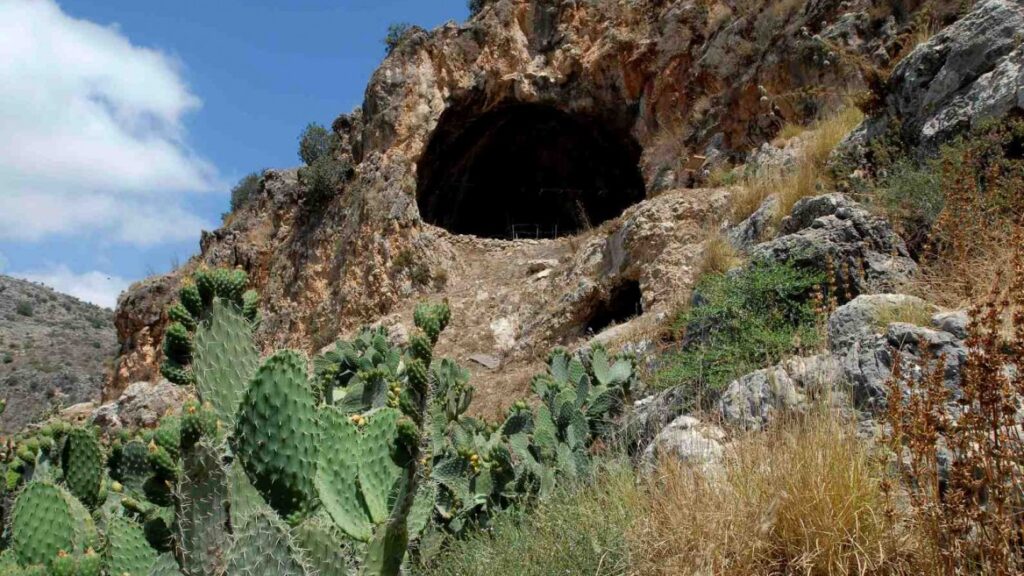

The dish was recovered during earlier excavations on the loch where at least 17 crannogs, or Iron Age wooden houses, were once dotted up and down the water.

Built from alder with a life span of around 20 years, the structures simply collapsed into the loch once they had served their purpose, with an incredible array of objects taken with them.

Most Popular

Among them was the dish which, remarkably, still carried traces of butter made by this Iron Age community.

Rich Hiden, the archaeologist at the Scottish Crannog Centre, said the item had helped to illuminate the everyday life of the crannog dwellers who farmed the surrounding land, and grew barley and ancient wheats such as spelt and emmer, and reared animals.

The crannogs were probably considered high-status sites which offered good security as well as easy access to trading routes along the Tay and into the North Sea.

Mr Hiden said conditions at the bottom of the loch had offered the perfect environment to preserve the butter and the dish.

He said: “Because of the fantastic anaerobic conditions, where there is very light, oxygen or bacteria to break down anything organic, you get this type of sealed environment.

“When they started excavating, they pulled out this square wooden dish, well around three-quarters of a square wooden dish, which had these really nice chisel marks on the sides as well as this grey stuff.”

Liped analysis on this matter found that it was dairy material, with experts believing it likely originated from a cow. Holes in the bottom of the wooden dish further suggest that it was used for the buttering process.

Cream would have been churned until thickened until it splits to form the buttermilk, with a woven cloth – possibly made from nettle fibres – placed in the dish with the clumps of cream and then further pushed through to separate the last of the liquid.

The butter then may have been turned into cheese by adding rennet, which naturally forms in a number of plants, including nettles.

Mr Hiden said: “This dish is so valuable in many ways. To be honest, we would expect people of this time to be eating dairy. In the early Iron Age, they had mastered the technology of smelting iron ore into to’s so mastering the technology of dairy we would expect.

“So while it may not surprise us that they are eating dairy, what is so important about this butter dish is that it helps us to identify what life was like in the crannogs and the skills and the tools that they had

“To me, that is archaeology at its finest. It is using the object itself to unravel the story. The best thing about this butter dish is that is so personal and offers us such a complete snapshot of what was happening here.

He added: “It is not just a piece of wood. You look at it and you start to extrapolate so much. If you start to pull one thread, you look at the tool marks and you see they were using very fine chisels to make this kind of object. They were probably making their own so that gives another aspect as to how life was here.”

It is believed that 20 people and animals lived in a crannog at any one time. Many trees were used to fashion the homes, with the Iron Age residents having a solid knowledge of trees with their houses thatched with reed and bracken.

Hazel was woven into panels to make walls and partitions.

Plans are underway to relocate the Scottish Crannog Centre to a bigger site at Dalerb, with three to four crannogs to be built in the water there.