Baby Buried With Care 10,000 Years Ago Found in Italian Cave

Archaeologists studying a cave in Liguria, Italy, have found the earliest known burial of a female infant in Europe. Surrounded by grave goods, the baby, whom the researchers dubbed “Neve” in honor of a nearby river, was 40 to 50 days old when she died about 10,000 years ago, reports Brian P. Dunleavy for United Press International (UPI).

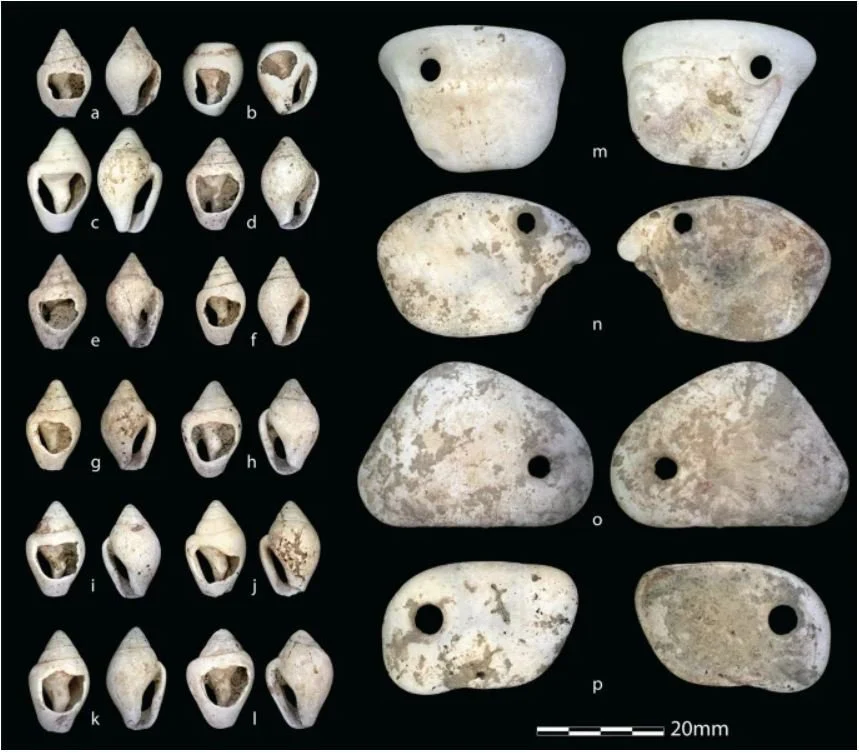

The child’s remains were wrapped in a shroud adorned with more than 60 beads and four pendants, all of which were made out of shells. An eagle-owl talon that may have been a gift was discovered nearby.

As the team argues in the journal Scientific Reports, the burial reflects the infant’s treatment as a full person by an early Mesolithic hunter-gatherer culture, with the items buried alongside her indicating significant emotional investment.

Finding the bones of babies from prehistoric or ancient times is rare because they’re extremely fragile, reports Tom Metcalfe for National Geographic. The new discovery is especially unusual because the remains were preserved well enough to extract DNA. In most cases, infants’ bone DNA has deteriorated too much to determine sex.

Adult burials dated to more than 14,000 years ago are somewhat common archaeological finds. But examples from the early Mesolithic (around 10,000 B.C.E.) are few and far between.

“The number of burials at this time, between about 10,000 and 11,000 years ago, is very, very rare,” lead author Jamie Hodgkins, an archaeologist at the University of Colorado, tells National Geographic. “… [I]t’s in a gap where we don’t have much of anything at all.”

Neve’s grave is located in the Arma Veirana cave in the mountains of Liguria, a region in northwestern Italy. A popular spot for visitors, the site is also a target for thieves. The researchers began studying the cave in 2015 after looters exposed late Ice Age tools there, writes Ian Randall for the Daily Mail.

Signs of activity in the cave date back more than 50,000 years, to a time when its most likely inhabitants would have been Neanderthals. Archaeologists found boar and elk bones that showed signs of butchering, as well as charred animal fat. After digging deeper into the cave in 2017, the team found the infant’s burial site.

“I was excavating in the adjacent square and remember looking over and thinking, ‘That’s a weird bone,’” says study co-author Claudine Gravel-Miguel, an archaeologist at the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University, in a statement.

The team fully excavated the gravesite in 2018. The ornaments buried with Neve were made with care; judging from patterns of wear, they were probably passed down to the child by other members of her community.

“The presence of perforated shells with traces of prolonged use means that these have been worn for a long time by the adults,” study co-author Fabio Negrino, an archaeologist at the University of Genoa, tells Rachel Elbaum of NBC News. “These shells were perhaps sewn to her dress.”

Tests conducted on the infant’s teeth revealed details of her short life. According to the study, carbon and nitrogen analysis found that before she was born, her mother ate a land-based diet. Neve experienced stress in the womb that led her teeth to temporarily stop growing. DNA and protein tests showed that she belonged to a European lineage known as the U5b2b haplogroup.

Researchers compared the find to the remains of two infants buried at Upward Sun River in Alaska some 11,500 years ago and rediscovered in 2013. In both cases, the infant girls appear to have been recognized as people in their own right.

This acknowledgement of personhood may have stemmed from a common ancestral culture, write the authors in the study. Alternatively, it could have arisen independently.

María Martinón-Torres, a paleoanthropologist who was not involved in the study, tells National Geographic that evidence of children’s personhood dates back to the early Homo sapiens and Neanderthal periods.

She adds, “The earliest documented burials in Africa … involve children and a deliberate dedication to the way the body is disposed.”

In a separate statement, Hodgkins says, “Archaeological reports have tended to focus on male stories and roles, and in doing so have left many people out of the narrative. … Without DNA analysis, this highly decorated infant burial could possibly have been assumed male.”