Ancient Aramaic Incantation Describes ‘Devourer’ that Brings ‘Fire’ to Devourer’ that Brings ‘Fire’ to Victims

A 2,800-year-old incantation, written in Aramaic, describes the capture of a creature called the “devourer” said to be able to produce “fire.”

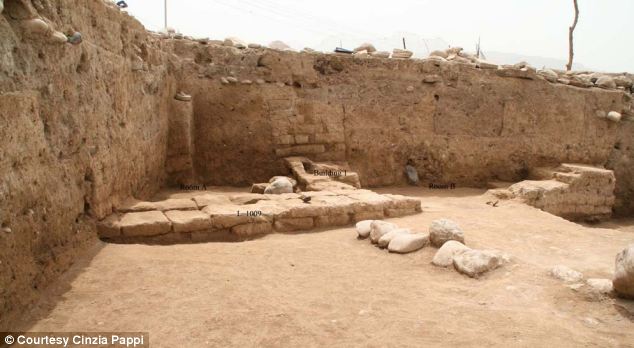

Discovered in August 2022 within a small building, possibly a shrine, at the site of Zincirli (called “Sam’al” in ancient times), in Turkey, the incantation is inscribed on a stone cosmetic container.

Written by a man who practiced magic who is called “Rahim son of Shadadan,” the incantation “describes the seizure of a threatening creature [called] the ‘devourer,'” wrote Madadh Richey and Dennis Pardee in the abstract of a presentation they gave recently at the Society of Biblical Literature annual meeting. That event took place in Denver between Nov 17 and 21.

The blood of the devourer was used to treat someone who appears to have been suffering from the “fire” of the devourer, said Richey, a doctoral student in the Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago.

It’s not clear whether the blood was given to the afflicted person in a potion that could be swallowed or whether it was smeared onto their body, Richey told . [Cracking Codices: 10 of the Most Mysterious Ancient Manuscripts]

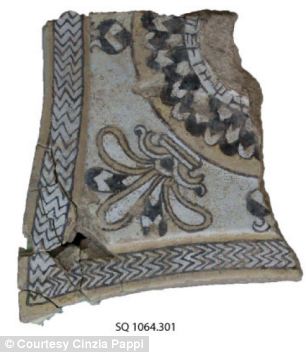

“Accompanying the text are illustrations of various creatures, including what appears to be a centipede, a scorpion and a fish,” wrote Richey and Pardee, who is the Henry Crown professor of Hebrew studies at the University of Chicago, in the abstract. The illustrations are found on both sides of the cosmetic container.

The vessel would have originally stored makeup, and it appears to have been reused for the purpose of writing this incantation, said Virginia Herrmann, who is co-director of the Chicago-Tübingen Expedition to Zincirli, the team that uncovered the incantation.

What is the “devourer?”

The illustrations suggest that the “devourer” may actually be a scorpion or centipede; as such, the “fire” may refer to the pain of the creatures’ sting, Richey .

In fact, scorpions pose a hazard to archaeologists working at the site. “We always have to check our shoes and bags for scorpions on the excavation, even though most of the local scorpions do not have a very dangerous venom,” said Herrmann, noting that shortly after the incantation was removed from the site, “one of our local workers was stung by a scorpion that had crawled onto his backpack that was sitting on the ground,” and the archaeological team rushed to apply first aid.

Long life

Analysis of the incantation’s writing indicates that it was inscribed sometime between 850 B.C. and 800 B.C., said Richey, adding that this makes the inscription the oldest Aramaic incantation ever found. However, the small building where the incantation was found appears to date to more than a century later, to the late eighth or seventh century B.C., Herrmann .

This suggests that the incantation was considered important enough that it was kept long after Rahim would have inscribed it, Herrmann said. [5 Ancient Languages Yet to Be Deciphered]

The incantation “had a significance that long outlived its original owner,” Herrmann said. It was not the only artifact found in the small building that was kept long after it was created, she said, noting that a “statuette base of a crouching lion made of polished black stone with red inlaid eyes” was also discovered there.

That lion figure appears to have been made in the 10th or ninth century B.C. The statuette base may have “once supported a metal figurine of a striding deity,” Herrmann added.

Sam’al, where the building is located, was the capital of a small Aramaean kingdom that flourished between roughly 900 B.C. and 720 B.C., said Herrmann, noting that the city was seized by the Assyrians around 720 B.C.