Archaeologists Have Discovered a Pristine 45,000-Year-Old Cave Painting of a Pig That May Be the Oldest Artwork in the World

Archaeologists believe they have discovered the world’s oldest-known representational artwork: three wild pigs painted deep in a limestone cave on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi at least 45,500 years ago.

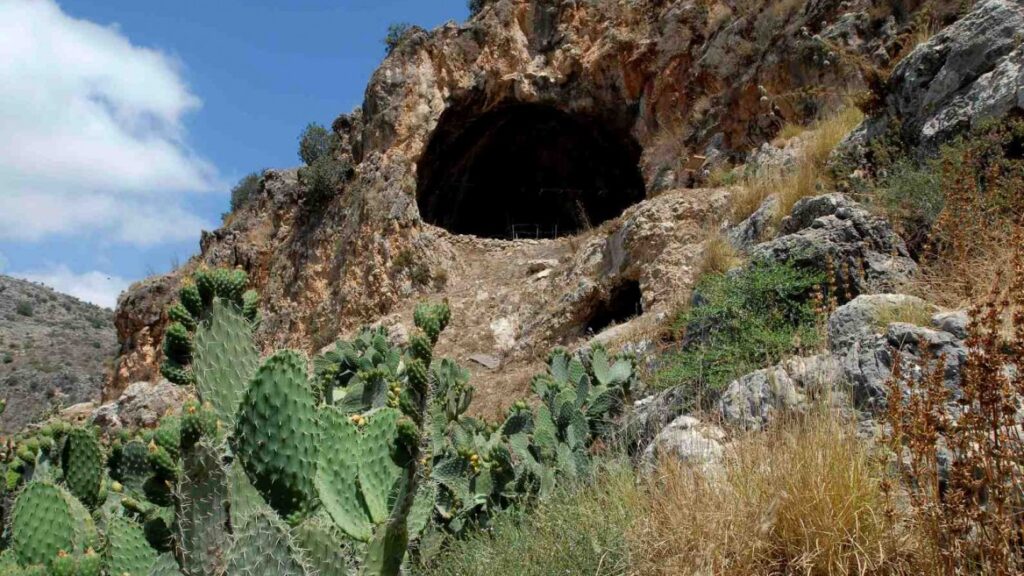

The ancient images, revealed this week in the journal Science Advances, were found in Leang Tedongnge cave. Made with red ochre pigment, the painting appears to depict a group of Sulawesi warty pigs, two of which appear to be fighting. Those two images are badly damaged, but the third, possibly watching the drama unfold, remains in near-pristine condition.

“The world’s oldest surviving representational image of an animal,” the paper noted, the painting “may also constitute the most ancient figurative artwork known to archaeology.”

“I was struck dumb,” Adam Brumm of Griffith University, Australia, the article’s lead author, told NewScientist. “It’s one of the most spectacular and well-preserved figurative animal paintings known from the whole region, and it just immediately blew me away.”

Archaeologist Basran Burhan, a Griffith University PhD student, discovered the cave and its prehistoric paintings in 2022. It’s only accessible during the dry season, via a long trek over mountains through a rough forest path.

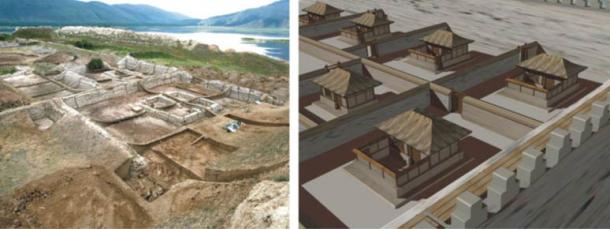

Previously, the oldest-known figurative art was actually from a nearby cave, Leang Bulu’Sipong, discovered by the same team. Announced in late 2022, that 43,900-year-old work depicts eight figures with weapons in hand approaching wild pigs and small native buffaloes. In 2022, the archaeologists also made headlines with the discovery of an animal painting at least 35,700 years old, and hand stencils from some 40,000 years ago.

As for the oldest art in the world, “it depends on what definition of ‘art’ you use,” Griffith University archaeologist Maxime Aubert, one of the paper’s co-authors, told National Geographic.

Some archaeologists believe that red markings found in a South African cave in 2022 represent the world’s first known drawings, created an astonishing 73,000 years ago, and 64,000-year-old Neanderthal cave paintings were discovered in Spain in 2022.

Such discoveries in Indonesia throw into question long-held beliefs that art originated in Europe, where sites like Spain’s El Castillo cave and France’s Chauvet cave feature work from 35,000 to 40,000 years ago.

The newest find “adds further weight to the view that the first modern human rock art traditions probably did not arise in Ice Age Europe as long assumed,” Brumm told Smithsonian magazine.

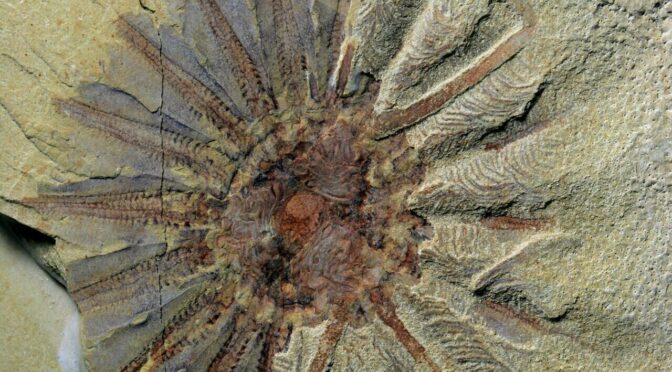

To date the newly found Sulawesi artwork, Brumm’s team applied uranium-series dating—a somewhat controversial technique—to a calcite mineral crust that covered part of the best-preserved of the three pigs.

Created by water dripping down the cave walls, the mineral formation contains uranium. The theory is that, based on how much of that uranium has decayed, scientists can figure out a minimum date for the painting underneath.

Despite the artworks’ advanced age, “the people who made it were fully modern, they were just like us, they had all of the capacity and the tools to do any painting that they liked,” Aubert told Agence France Presse.

But other experts not involved with the study are less certain that homo sapiens necessarily created the images.

“An anatomically modern human is an anatomical definition. It has nothing to do with cognition, intelligence or behavior,” University of Barcelona archaeologist João Zilhão told the New York Times. “There is no evidence about the anatomy of the people who did this stuff.”

Regardless of the species responsible, the paintings provide clues about what life was like in ancient Sulawesi, suggesting the importance of the warty pig to hunter-gatherer society.

“These are small native pigs that are endemic to Sulawesi and are still found on the island, although in ever-dwindling numbers,” Brumm told Smithsonian. “The common portrayal of these warty pigs in the Ice Age rock art also offers hints at the deep symbolic significance and perhaps spiritual value of Sulawesi warty pigs in the ancient hunting culture,”

Another newly discovered pig painting from a nearby cave dated with the same method was found to be 32,000 years old, and more similarly significant finds may be forthcoming.

“We have found and documented many rock art images in Sulawesi that still await scientific dating,” study coauthor Adhi Agus Oktaviana, a PhD student at Griffith, told CNN. “We expect the early rock art of this island to yield even more significant discoveries.”