Unraveling the Mystery of the “Armenian Stonehenge”

The misty and mountainous valleys of the south Caucasus have been host to human activity continuously for thousands of years, but only recently has the Western archaeological world had access to them.

From the cave in which researchers found the world’s oldest shoe and the oldest winemaking facility, to traces of an Urartian city with hundreds of wine-holding vessels buried in the ground, the last four decades have witnessed extraordinary interest from scholars and tourists alike in the smallest republic in the former Soviet Union. None, however, are as quite as tantalizing as the 4.5 hectare archaeological site whose name is as contested as its mysterious origins.

Located in Armenia’s southernmost province, Zorats Karer, or as it is vernacularly known, Karahundj, is a site which has been inhabited numerous times across millennia, from prehistoric to medieval civilizations.

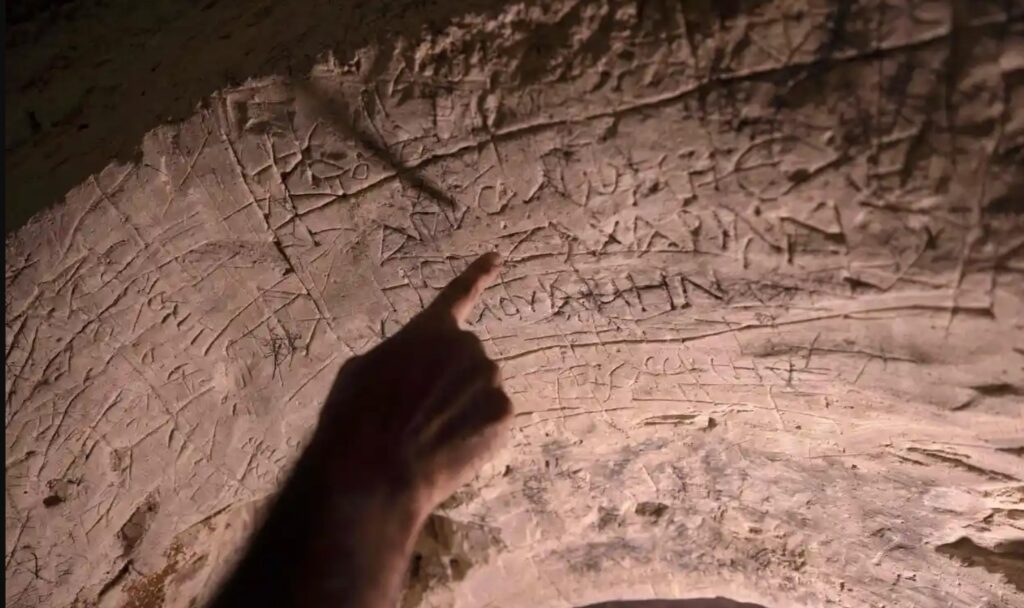

It consists of a prehistoric mausoleum and nearby, over two hundred neighboring large stone monoliths, eighty of which have distinctive, well-polished holes bored near their upper edge.

In recent years, to the dismay of local scientists, the monoliths have garnered the interest of the international community after some pre-emptive research emerged drawing comparisons between the astronomical implications of Zorats Karer and that of the famous Stonehenge monument in England.

Many touristic outlets responded to the comparison by branding Zorats Karer colloquially as the ‘Armenian Stonehenge’ and the resulting debate between the scientific community and popular culture has been a fierce one.

The first scholarly account of Zorats Karer took place in 1935 by ethnographer Stepan Lisitsian, who alleged that it once functioned as a station for holding animals. Later, in the 1950s, Marus Hasratyan discovered a set of 11th to 9th century BCE burial chambers.

But the first investigation which garnered international attention to the complex was that of Soviet archaeologist Onnik Khnkikyan, who claimed in 1984 that the 223 megalithic stones in the complex may have been used, not for animal husbandry, but instead for prehistoric stargazing.

He believed the holes on the stones, which are two inches in diameter and run up to twenty inches deep, may have been used as early telescopes for looking out into the distance or at the sky.

Intrigued by the astronomical implications, the next series of investigations were conducted by an astrophysicist named Elma Parsamian from the Byurakan Astrophysical Observatory, one of the main astronomy centers of the USSR.

She and her colleagues observed the position of the holes according to an astronomical calendar and established that several of them aligned with the sunrise and sunset on the day of the summer solstice.

She is also responsible for suggesting the name Karahundj for the site, after a village 40km away by the same name. Prior to her investigations, locals referred to the site as Ghoshun Dash, which meant ‘Army of Stones’ in Turkic.

Folk myth suggests the stones were erected in ancient times to commemorate soldiers killed in war. After the 1930s, locals transitioned to the Armenian translation, Zorats Karer. But Karahundj, Parsamian said, offered a more interesting name because Kar, means stone and hundj, a peculiar suffix which has no meaning in Armenian, sounds remarkably similar to the British ‘henge’.

In recent years, this name has received extreme criticism from scholars and in scientific texts, the name Zorats Karer is used nearly exclusively.

Several years later, a radiophysicist named Paris Herouni performed a series of amateur studies branching off from Parsamian’s, using telescopic methods and the precession laws of Earth. He argued that the site actually dates back to around 5500 BCE., predating its British counterpart by over four thousand years.

He strongly pioneered for a direct comparison to Stonehenge and even went so far as to etymologically trace the name Stonehenge to the word Karahundj, claiming it really had Armenian origins. He was also in correspondence with the leading scholar of the Stonehenge observatory theory, Gerald Hawkins, who approved of his work. His claims were quick to catch on, and other scholars who strongly contest his finding have found them difficult to dispel.

The problem with the “Armenian Stonehenge” label, notes archaeo-astronomer Clive Ruggles in Ancient Astronomy: An Encyclopedia of Cosmologies and Myth, is that analyses that identify Stonehenge as an ancient observatory have today largely been dispelled. As a result, he says, the research drawing comparisons between the two sites is “less than helpful.”

According to Professor Pavel Avetisyan, an archaeologist at the National Academy of Sciences in Armenia, there is no scientific dispute about the monument. “Experts have a clear understanding of the area,” he says, “and believe that it is a multi-layered [multi-use] monument, which requires long-term excavation and study.”

In 2000, he helped lead a team of German researchers from University of Munich in investigating the site. In their findings, they, too, criticized the observatory hypothesis, writing, “… [A]n exact investigation of the place yields other results. [Zora Karer], located on a rocky promontory, was mainly a necropolis from the Middle Bronze Age to the Iron Age. Enormous stone tombs of these periods can be found within the area.” Avetisyan’s team dates the monument to no older than 2000 BCE, after Stonehenge, and also suggested the possibility that the place served as a refuge during times of war in the Hellenistic period.

“The view that the monument is an ancient observatory or that its name is Karahundj is elementary charlatanism, and nothing else. All of that,” says Avetisian, “has nothing to do with science.”

Unfortunately for Avetisyan, dispelling myths about Zorats Karer is difficult when so few resources exist in English to aid the curious Westerner. Richard Ney, an American who moved to Armenia in 1992, founded the Armenian Monuments Awareness Project and authored the first English-language resource to the site from 1997, has witnessed over two decades of back-and-forth.

He believes Karahundj is “caught between two different branches of science with opposing views on how to derive fact. Both are credible,” he says, “and I feel both can be correct, but will never admit it.”

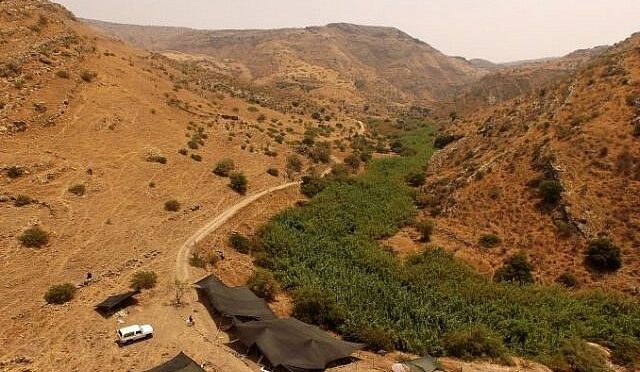

Despite all the controversy and whatever you end up deciding to call it, the monument itself is stunning and located in an area of Armenia well-endowed with natural beauty, making it an attractive journey for many tourists each year.

It’s even become an object of contemporary interest to young urbanites and neo-Pagans from Yerevan, who are known to celebrate certain solstices there. In many ways, Zorats Karer is a testament to the elusive nature of archaeology, and it’s perhaps the case that the mystery is–and will remain–part of its appeal.