Metal Detectorist Milly Hardwick Finds Bronze Age Hoard of Axe Heads

Her metal detector went crazy. Milly Hardwick, the 13-year-old English girl, had discovered ancient treasure. This September, Milly identified a rare archaeological Bronze Age hoard in a field near Royston, on the Hertfordshire/Cambridgeshire border in England.

There, in “Milly’s field” as it should now be called, archaeologists excavated about 200 Bronze Age artifacts. The question now is whether this Bronze Age hoard is a treasure or not? If so, Milly and her dad get rich, quick.

I am uncertain if this is a story of beginners’ luck, or maybe, a sharp reminder that you really do have to be in it, to win it. Young Milly discovered the rare Bronze Age hoard of about 65 axe heads on her third detecting trip with her father.

Now, English archaeologists have excavated about 200 Bronze Age items from surrounding archaeological sites. Together, the artifacts are being treated by authorities as a potential treasure hoard.

Unearthing A Bronze Age Hoard From 1,300 BC

The first Bronze Age hoard that Milly found back in September while on a detecting trip with her father comprised a collection of axe heads dating from about 1,300 BC.

Another group of detectorists, on the same field trip, were scanning close to Milly’s axes when they identified the second potential Bronze Age hoard. BBC reported that the collection of Bronze Age artifacts has now been sent to the British Museum for analysis and accurate dating.

Following UK metal detecting regulations to the line, the group of detectorists reported their discovery to the landowner, who had permitted them to detect on his land. Then together the discovery was reported to the local coroner’s office.

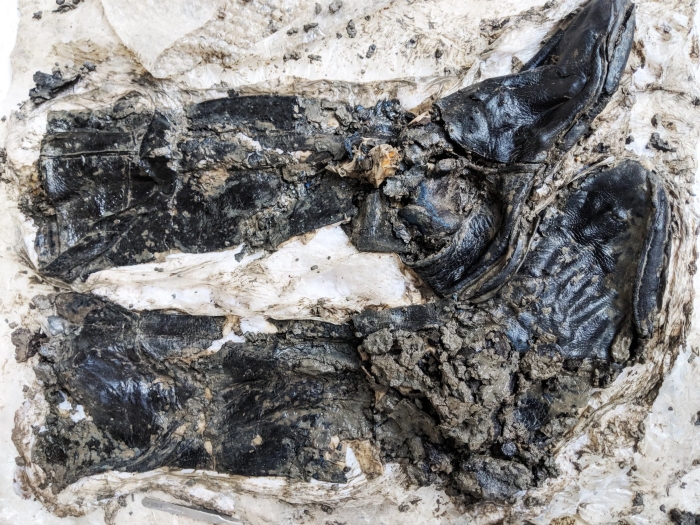

As soon as the very next morning a team of professional archaeologists from Cambridgeshire County Council and Oxford Archaeology East arrived at the site. The following day, both sites were excavated, and the hoards were revealed in all their ancient glory after having spent 3,300 years in the dark!

A Very Exciting Discovery

Royston Crow spoke with Councillor Lorna Dupré, chairwoman of the council’s environment and green investment committee. Dupré said we can “confirm that what we believe to be two Bronze Age hoards containing around 200 items have been found on land near to Royston.”

She added that the find is being treated as “two separate hoards, but related potential treasure cases” as is defined by the 1996 UK Treasure Act.

Dupré said the two hoards were a “very exciting discovery.” What’s special with this collection of Bronze Age hoard artifacts is that such a wide variety of tools and weapons were identified. Archaeologists have already found “socketed axe heads, winged axe heads, cake ingots and blade fragments, all of which are made of copper-alloy.”

In Bronze Age Britain alloys were traditionally made of copper and tin. While this alchemy was practiced as early as 3000 BC, Bronze weapons, tools, and ritual artifacts were not made on a mass scale until much later, in the so-called Bronze Age, between 2,500 BC and 800 AD.

A Treasure or Not? This is The Big Money Question!

Milly Hardwick and her father followed UK treasure discovery protocols by immediately reporting their discovery to their local coroner’s office, albeit they had 14 days to do so. Smithsonian reports that the coroner’s office is now responsible for determining if the discoveries officially qualify as treasure through the English Portable Antiquities Scheme.

After the collection has been assessed and valued, if it is indeed declared a treasure hoard, it’s a hay day for the Hardwicks. At such times, English museums will line up to purchase the collection of artifacts. If this happens, the young metal detectorist says she will split the income with the field’s owner, but not a single mention of old dad getting so much as a halfpenny. Typical teen!