More than a Dozen Mysterious Prehistoric Tunnels in Cornwall, England, Mystify Researchers

More than a dozen tunnels have been found in Cornwall, England, that are unique in the British Isles. No one knows why Iron Age people created them.

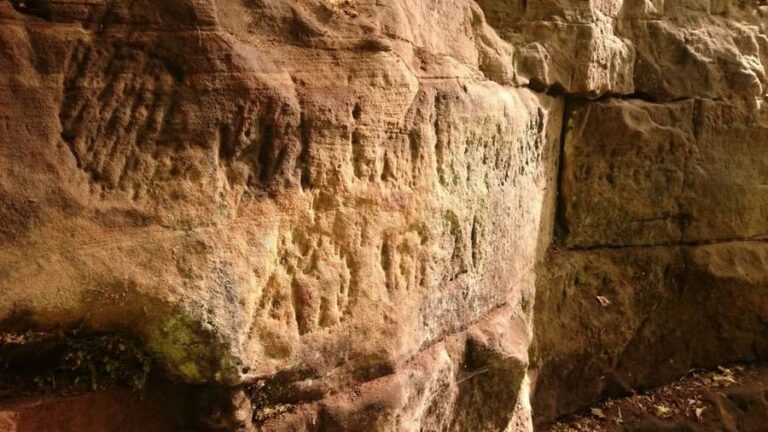

The fact that the ancients supported their tops and sides with stone, suggests that they wanted them to endure, and that they have, for about 2,400 years.

Many of the fogous, as they’re called in Cornish after their word for cave, ogo, were excavated by antiquarians who didn’t keep records, so their purpose is hard to fathom, says a BBC Travel story on the mysterious structures.

The landscape of Cornwall is covered with hundreds of ancient, stone, man-made features, including enclosures, cliff castles, roundhouses, ramparts and forts.

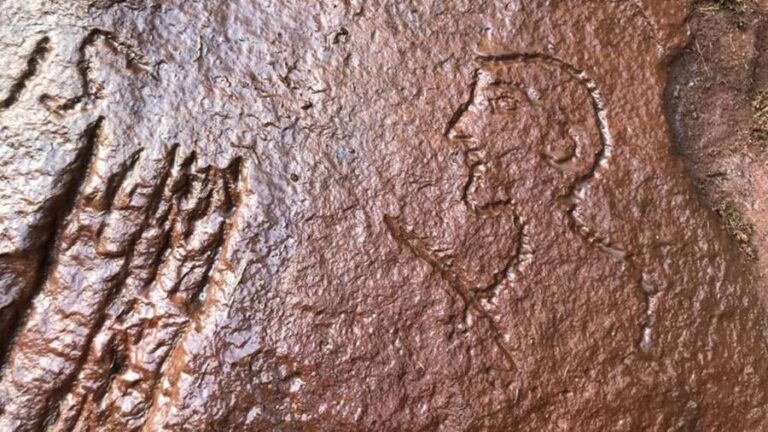

In terms of stone monuments, the Cornwall countryside has barrows, menhirs, dolmens, cairns and of course stone circles. In addition, there are 13 inscribed stones.

“Obviously, all of this monument building did not take place at the same time. Man has been leaving his mark on the surface of the planet for thousands of years and each civilisation has had its own method of honouring their dead and/or their deities,” says the site Cornwall in Focus.

The site says Cornwall has 74 Bronze Age structures, 80 from the Iron Age, 55 from the Neolithic and one from the Mesolithic. In addition, there are nine Roman sites and 24 post-Roman.

The Mesolithic dates from 8000 to 4500 BC, so people have been occupying this southwestern peninsula of Britain for a long, long time.

About 150 generations of people worked the land there. But it’s believed the fogous date to the Iron Age, which lasted from about 700 BC to 43 AD. Though they’re unique, the fogou tunnels of Cornwall are similar to souterrains in Scotland, Ireland, Normandy and Brittany, says the BBC.

The fogous required considerable investment of time and resources “and no one knows why they would have done so,” says the BBC. It’s interesting to note that all 14 of the fogous have been found within the confines of prehistoric settlements.

Because the society was preliterate, there are no written records that explain the enigmatic structures.

“There are only a couple that have been excavated in modern times – and they don’t seem to be structures that really easily give up their secrets,” Susan Greaney, head properties historian of English Heritage, told the BBC.

The mystery of their construction is amplified at Halliggye Fogou, the best-preserved such tunnel in Cornwall. It measures 1.8 meters (5.9 feet) high. The 8.4 -meter-long (27.6 feet) passage narrows at its end in a tunnel 4 meters (13.124 feet) long and .75 meter (2.46 feet) tall.

Another tunnel 27 meters (88.6 feet) long branches off to the left of the main chamber and gets darker the farther in one goes. There is what the BBC calls a “final creep” at the end of this passage that has stone lip upon which one could trip.

“In other words, none of it seemed designed for easy access – a characteristic that’s as emblematic of fogous as it is perplexing,” wrote the BBC’s Amanda Ruggeri.

Some have speculated they were places to hide, though the lintels of many of them are visible on the surface and Ruggeri says they would be forbidding places to stay if one sought refuge.

Still others have speculated they were burial chambers. An antiquarian who entered Halliggye in 1803 wrote that it had funerary urns. But others entered by the hole he made in the roof, and all the urns are gone.

No bones or ashes have been discovered in the six tunnels that modern archaeologists have examined. No remnants of grains have been found, perhaps because the soil is acidic. No ingots from mining have been discovered.

This elimination of storage, mining or burial purposes has led some to speculate that they were perhaps ceremonial or religious structures where people worshiped gods.