Bronze Age time capsule: 3,000-year-old vitrified food found in jars in England

Archaeologists have the opportunity to discover how people in the late Bronze Age lived and what they ate by excavating a dwelling destroyed by fire 3,000 years ago in Cambridgeshire County, England.

Researchers are calling the site a time capsule, as vitrified food—meaning it has become like glass—has been found in jars at the site.

Archaeologists also have found rare small pots and exotic glass beads at the site, which will be studied with a £1.1 million ($1.73 million) research project over a nine-month period. They think it was a settlement of prosperous people.

Another major find at the site came in 2016 when a huge timber wheel was discovered. It is one of the largest Bronze Age wheels to have been unearthed by archaeologists anywhere in the world.

The wheel measures a meter (3.28 ft.) in diameter and 3.5 centimeters (1.38 inches) thick. Archaeologists believe it would have originally had a heavy duty leather tire.

These dimensions and the style of the wheel have lead archaeologists to suggest it was likely part of an ox-pulled cart.

The settlement was buried in the wet fens but is being excavated using earth-moving machinery. Previously in fens (wetlands), archaeological work was done only in shallow areas or near the edges of the fens, says MustFarm.com .

They call it ‘deep space archaeology’ because the remnants of the community are buried so deeply in the mire. MustFarm.com also calls it one of the most important European Bronze Age sites.

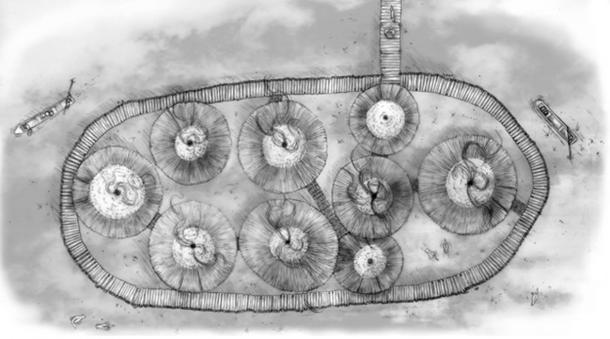

Must Farm in the Flag Fen Basin made news in 2011 when nine well-preserved log boats were unearthed there. The dwelling was encircled by wooden posts until a fire made it collapse in the river.

The fact that it was submerged helped preserve its contents, says Culture24 . Among the findings are decorated tiles made from lime tree bark.

The finds will be put on display at Peterborough Museum and other venues.

“Usually at a Later Bronze Age period site you get pits, post-holes and maybe one or two really exciting metal finds,” said archaeologist David Gibson of the Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

“It’s a fantastic chance to find out how people in the Late Bronze Age lived their daily lives, including how they dressed and what meals they ate.”

His colleague Kasia Gdaniec, the senior archaeologist with Cambridgeshire County Council, said: “We think those living in the settlement were forced to leave everything behind when it caught on fire. An extraordinarily rich range of goods and objects are present in the river deposits, some of which were found during an evaluation in 2006.”

The fact that the dwelling is preserved under water and was abandoned quickly means there could be great finds in the future, said Duncan Wilson of Historic England, comparing it to how the Mary Rose, a Tudor ship that sunk, was salvaged in the 1960s and shed a lot of light on those times.

“This could represent a moment of time from the Late Bronze Age comparable to the connection with the past made by the objects found with the Mary Rose,” he said.

“This site is internationally important and gives a fascinating insight into the lives of our ancestors.”