The World’s Smallest Elephants Led Unusually Long Lives

Ancient elephants that would have been born the size of a puppy lived for decades more than previously thought. Researchers studying an ancient miniature elephant that lived on Mediterranean islands found it could have lived for over 68 years, which is unusually long for a mammal of its size. The smallest-ever elephant took a leisurely approach to growing up, with a drawn-out development lasting up to 15 years.

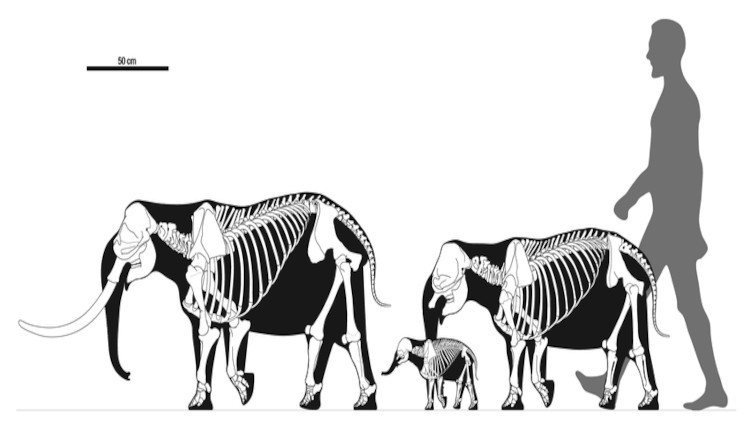

Though it was barely a meter tall, a team of European scientists found that Palaeoloxodon Falconeri grew much more slowly than its modern relatives, with modern African bush elephants entering adulthood four years earlier than their extinct relatives despite being much bigger.

Their findings contradict previous studies which suggest P. Falconeri would only have lived for 26 years, suggesting that the species would have lived for at least seven decades, and perhaps even longer.

Professor Meike Köhler, the paper’s lead author, says, ‘Traditionally this species had been considered to have a rapid development, reaching sexual maturity early and having a short life. Our work reveals that the life history of this elephant was much slower.

‘Organisms that grow at slower rates have fewer errors in biosynthesis which leads to an extended lifespan.’

Dr Victoria Herridge, who researches fossil elephants at the Museum and co-wrote the paper, says, ‘It’s hard to know why these elephants grew so slowly. There is an idea that the islands had limited resources and predators, so on the one hand food is scarce, but on the other, there is very low mortality.

‘This would allow for a slower investment in growth over a longer period, but without paying the price that smaller individuals pay on the mainland, such as a death in the jaws of a predator. However, the reasoning behind that is still debated.

‘There’s a lot we don’t know about this species, but its slower growth shifts our thinking a little bit on how these elephants evolved.’

Bigger is better

It’s been known for some time that when it comes to mammals and birds, larger animals live longer. While some shrews live for little more than a year, mammals at the other end of the weight spectrum can live for centuries.

The bowhead whale, which can grow up to 18 meters long or about the length of a bowling alley, has been estimated to have been over for over 200 years. Some bowheads have lived so long that they still contain Victorian harpoons used to try and kill them over a century ago.

While the relationship between size and lifespan generally holds across mammals and birds, lifestyle can have an impact. For instance, flying animals generally live longer than their ground-dwelling relatives, with small bats living for much longer than rats and shrews of a similar size.

However, there are a few notable exceptions. Naked mole rats can live for around 30 years, while humans have used technological innovations and medicine to allow us to live for longer too. Previously, it had been thought that the miniature elephants fitted well with the overall pattern.

After diverging from the largest elephant to ever live, the straight-tusked elephant, it was thought that P. Falconeri would have shortened its lifespan as it dwarfed over the millennia it was isolated on what is now the island of Sicily.

‘Palaeoloxodon Falconeri is the smallest elephant ever to have existed, living on both Malta and Sicily,’ says Victoria. ‘At the time, we didn’t know if the area was one large island or an archipelago in the Mediterranean.

‘They are remarkable animals. They were around a meter tall, which is about the same size as a newborn African elephant but they were adults. As babies, they would only have been the size of a puppy.’

While little is known about the species’ life, it is assumed to have grown smaller through a process of miniaturization which is common to many island species due to a lack of resources, predators and competitor species. Looking at the overall trend in life history for mammals, it was estimated that an elephant of this size would live for at least 26 years.

The new study analyzed the growth of teeth, bones and tusks from Spingallo Cave, near Siracusa in southeast Sicily, to provide a more accurate estimate, which shows the species is an exception to the rule.

Professor Antonietta Rossa, from the University of Catania, Sicily, where the fossils are housed and coauthor of the study, says, ‘Spinagallo Cave is outstanding for the number of remains. This abundance of bones provides enough material for analyzing specimens of different ages and growth stages.’

Good things come to those who wait

The researchers found that across the different types of remains studied, P. Falconeri grew very slowly. Though elephants are generally already slow-growing, this species was even more so. While most species grow rapidly as an infant before slowing down after reaching adulthood, the Sicilian elephants grew at a fairly constant rate throughout their entire lives.

Even the oldest specimens grew only two millimeters a year more slowly than the youngest, while the difference for African bush elephants is around a centimeter a year.

However, this slow growth was compensated for by a much longer developmental period, with some bones not showing signs of adulthood even by the age of 22. The age of sexual maturity was similarly delayed, with all evidence pointing towards 15 years in P. Falconeri, compared with 12 years in living African elephants.

‘Given the later age of sexual maturity, their gestation period may also have been longer or similar to large African elephants,’ says Victoria. ‘And of course, those newborns would also take a long time to grow up, leading to long generation times.’

Researchers have suggested that this long period of development could have resulted from a lack of predators in Sicily. This would allow the elephant to grow more slowly as there was little danger of infants being hunted.

As it was less likely to die, this meant that there was less evolutionary pressure for P. Falconeri to grow up fast and reproduce. As a result, selection pressures instead drove it to grow slowly, allowing more time for learning and development over decades rather than years.

However, this slow development would have put it at a disadvantage when it came to sudden changes. Longer development means that evolution acts more slowly, requiring many generations to make significant changes.

‘By taking the inferred age of sexual maturity we can see their gestation period may have been similar to large African elephants,’ Victoria says.

‘Even though it’s a lot smaller than a full-sized elephant, it’s behaving like a very large animal in terms of its generation time which makes it more vulnerable to extinction.

‘Island populations are already vulnerable to extinction because they are often unique and not very numerous so it all adds up.’

The period in which P. Falconeri lived was one of dramatic environmental and climatic change, with Sicily changing tectonic activity and sea level. This could have put even more pressure on the elephant’s limited resources and may have led to its extinction around 400,000 years ago.