Burned 3,000-Year-Old Settlement Frozen in Time May Have Been Torched by Raiding Party

Archaeologists believe that an raiding party torched a village of the Bronze Age on stilts well preserved in the silt of the river, which fell into about 3000 years ago.

Many findings at the site just east of Peters-borough, England, including palisades made of new wood, indicate that a little while before they burned, people had lived there.

The site is at 120 km (74.5 miles) north of Must Farm in a quarry. An archeologist found out in 1999 when he saw wooden stakes or palisades sticking out of the mud and silt that protects them and many other artifacts. Scorching and charring wood also contributed to preserving some of the material.

A website on this site and excavations says: “At some point after the palisade, a fire was created in the area causing the platform to fall into the river underneath which immediately extinguished the flames.

As the material lay on the riverbed it was covered with layers of non-porous silt which helped to preserve everything from wooden utensils to clothing. It is this degree of preservation which makes the site fascinating and gives us hundreds of insights into life during the Bronze Age.”

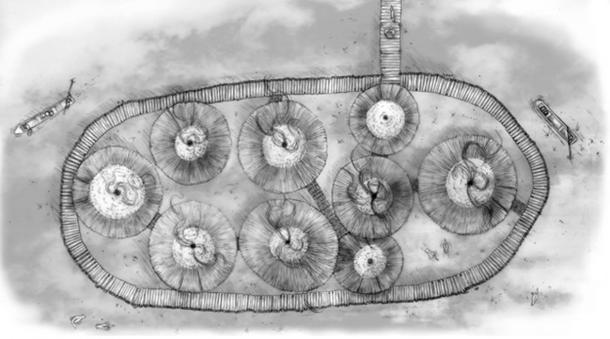

Along with its nine log boats, nine roundhouses and other main objects, the entire site is amazing, two of the most interesting finds were textiles and vitrified food.

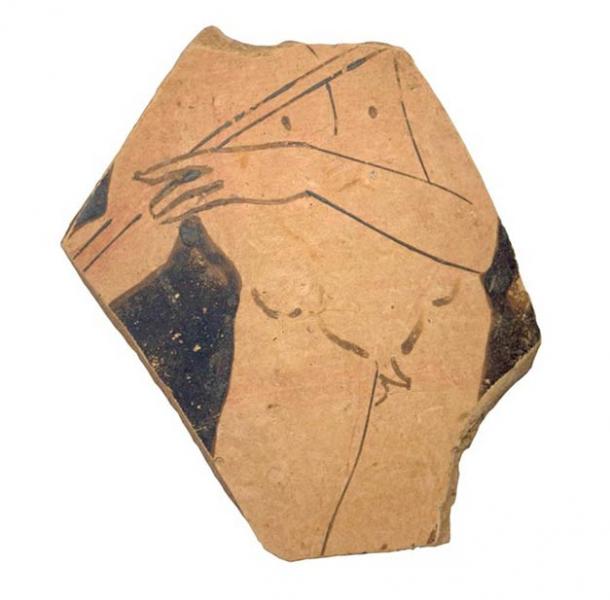

Also, beads, likely from the Balkans and the Middle East, showed there was long-distance trade in Britain, where the Bronze Age began about 4,000 to 4,500 years ago.

The purpose of the textiles has not been discovered because there are no telltale clues such as cuffs to say whether it was used for clothing or other purposes.

However, one of the team members, Susanna Harris of Glasgow University, said they have found fine linen with thread counts of 30 per centimeter, as fine as any cloth known from Europe of the time. “I counted them several times, thinking ‘This can’t be right,’” Harris told

Archaeologists working on Must Farm revealed some of their findings to the media this week. Now they intend to retreat into the laboratory to more closely examine and analyze the many artifacts they have discovered at this site.

It’s the best Bronze Age settlement ever found in the United Kingdom,” said Mark Knight, project manager with the Cambridge Archaeological Unit, a private company that is in charge of the excavations. “We may have to wait a hundred years before we find an equivalent.”

The archaeologists say the roundhouses were about 8 meters (26.25 feet) in diameter. They were built above the water as a defense and to facilitate trade on the river, which led to the North Sea and other farms in the area.

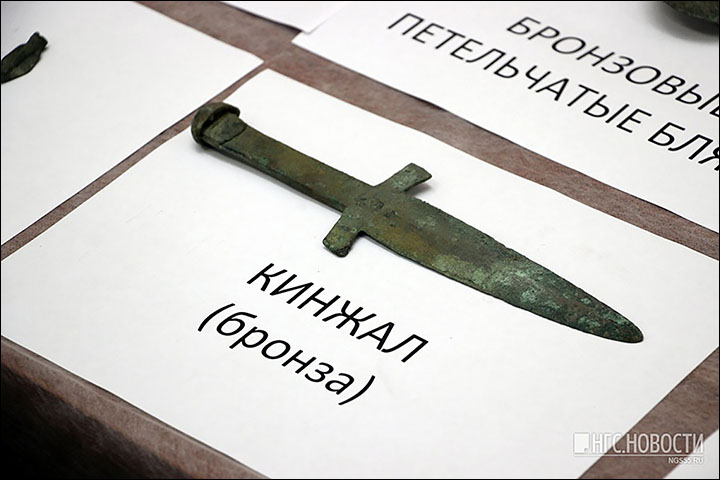

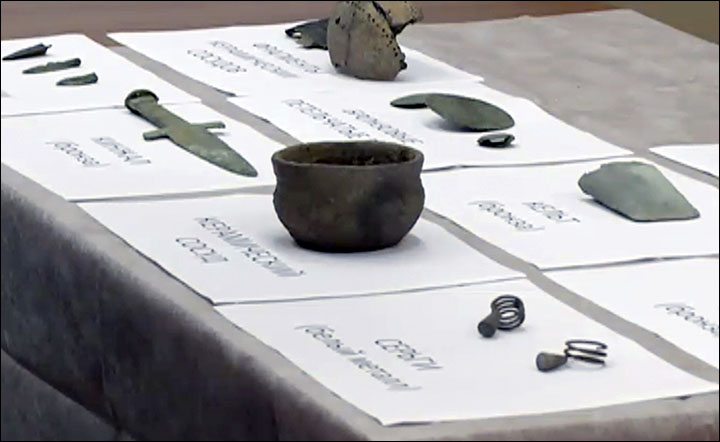

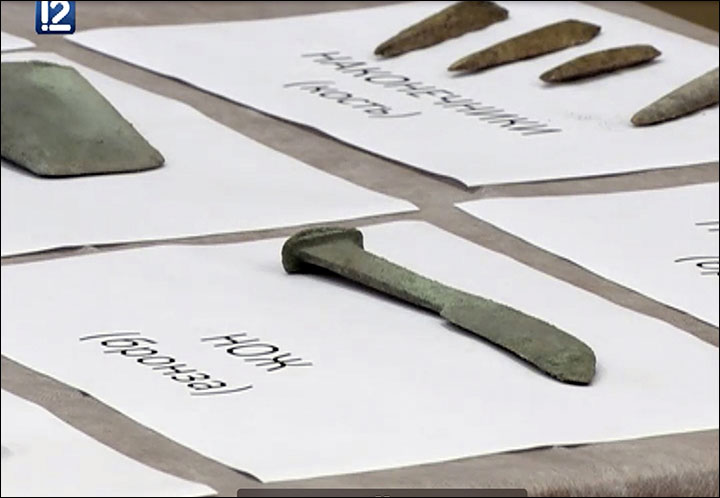

Each house had woodworking tools, including chisels, axes and gouges. They also had sickles to reap grain, spears for hunting and perhaps fighting, and sets of ceramics that contained tiny cups, fine bowls and storage jars.

In the northeast sector of each house were butchered lambs. Dumped into the river were parts of deer and wild pigs. The archaeologists speculate the inhabitants may have had a taboo against butchering wild game indoors.

Several food vessels contain charred, wheat, barley and residues of food that had already been cooked. One bowl of stew had a spoon in its burned crust. Experts hope to get Bronze Age recipes from the prehistoric smorgasbord.

Tree rings from wood used to construct the roundhouses and palisade were from about 1290 to 1250 BC and were all green and undisturbed by insects. That, plus wood chips found there, tell archaeologists it was a new settlement when it burned.

Archaeologist Karl Harrison of Cranfield University has been analyzing the fire damage and scorch marks to determine if the fire started in a house or outside.

If it started inside, it may have been from a cook fire. If the blaze started outside, it might have been a case of arson. “It was rapid, smoke-filled, and incredibly destructive,” he told

The people never returned to the site, which ensured it was well-preserved for modern archaeologists to discover and analyze.