Archaeologists in Italy Unearth Marble Bust of Rome’s First Emperor, Augustus

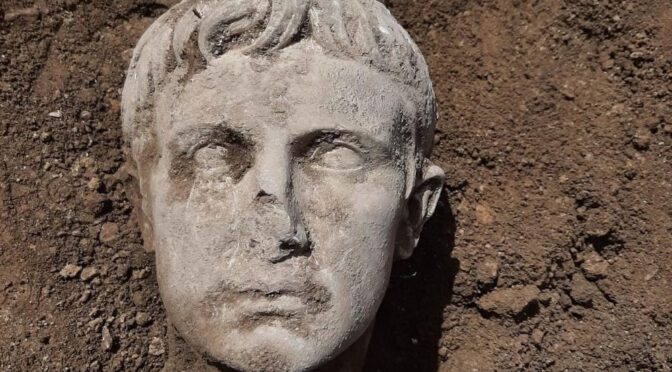

Last week, construction workers conducting renovations in Isernia, a town in south-central Italy, unearthed a long-lost portrait of an ancient ruler: namely, a weathered marble head that dates to the days of the Roman Empire.

Researchers suspect that the marble figure depicts Augustus, who ruled as the first Roman emperor from 27 B.C. to until his death in 14 A.D. The adoptive son of Julius Caesar, Augustus oversaw a period of immense colonization and imperial growth.

Besides a badly damaged nose—and the loss of the rest of its body—the head has remained relatively intact, according to a statement released on Facebook by the local government’s archaeology department.

Scholars discovered the head while renovating Isernia’s historic city walls, parts of which were constructed under imperial Rome, reports Italian news agency ANSA.

As local news station isNews notes, the walls collapsed during previous excavation work; efforts to rebuild them have proven controversial in the small town.

Speaking with isNews, superintendent Dora Catalano and archaeologist Maria Diletta Colombo, both of whom are overseeing the new project, said that some locals had proposed supporting the historic walls with concrete pillars.

“We highlighted that the solution was not feasible, not in the least because the piling would have risked destroying the foundation of the walls and any traces of ancient presence in the area,” the pair explained, per Google Translate.

Instead, the archaeologists—who began work on March 30—are striving to restore the walls in a way that strengthens their structural integrity while preserving their cultural heritage.

“Yes, it is really him, the emperor Augustus, found today during the excavation,” writes the Archaeological Superintendency of Molise in the statement, per a translation by ARTNews’ Claire Selvin. “Because behind the walls of a city [lies] its history, which cannot be pierced with a concrete [pillar].”

Per a separate report from isNews, Mayor Giacomo D’Apollonio announced that the rare artifact will remain in Isernia and eventually go on display in the nearby Museum of Santa Maria Delle Monache.

The find testifies to the Romans’ presence in the ancient colony of Isernia, then known as Aesernia. Throughout the first century B.C., neighboring powers in Italy fought for control of the small town, which was strategically located as a “gateway” for expansion into the peninsula, writes Barbara Fino for local newspaper Il Giornale del Molise.

Roman forces first captured Isernia around 295 B.C. Its previous occupants, the Samnites, a group of powerful tribes from the mountainous south-central Apennine region, retook the city in 90 B.C. after a prolonged siege.

As John Rickard notes for Historyofwar.org, the siege took place during the Social War, a three-year clash between the Roman Republic and its longtime allies, who wanted to be recognized as Roman citizens.

“Most insurrections are people trying to break away from some power—the Confederacy tries to break away from the United States, the American colonies try to break away from the British—and the weird thing about the Social War is the Italians are trying to fight their way into the Roman system,” Mike Duncan, author of The Storm Before the Storm: The Beginning of the End of the Roman Republic, told Smithsonian magazine’s Lorraine Boissoneault in 2017.

“The ultimate consequences of allowing the Italians to become full Roman citizens was nothing. There were no consequences. Rome just became Italy and everybody thrived, and they only did it after this hugely destructive civil war that almost destroyed the republic right then and there.”

Pper Il Giornale del Molise, Roman forces soon recaptured the town and razed most of it to the ground, rebuilding the city as a Roman center.

As isNews reports, researchers identified the newly unearthed head as a portrait of Augustus based on his “swallow-tail” hairstyle: thick strands of hair that are divided and parted in a distinctive “V” or pincer shape.

In general, this portrait tracks closely with the Primaporta style of facial construction. Popularized around 20 B.C., this style became the dominant way of depicting Augustus in official portraits, according to the University of Cambridge. These statues’ smooth features and comma-shaped locks emphasized the ruler’s youth.