A 1,600-year-old basilica re-emerged due to the withdrawal of waters from lake iznik

The 1600-year-old basilica found under Lake Iznik in crystal clear water shows breathtaking aerial images. Archeologists and art historians believe that after an earthquake in 740, the religious structure collapsed during an earthquake in 740, before sinking further into the lake.

The underwater building lies between 1.5 and 2 meters below the sea and can be clearly seen for the first time, as the coronavirus lockdown has resulted in less water pollution.

The local authority recently flew a drone over the site to take stunning images, revealing the basilica’s walls and structure just below the lake’s surface.

In 2014, when it was first found by experts, the Archaeological Institute of America named the basilica one of the top 10 discoveries of the year. It was discovered while photographing the area from the air for an inventory of historic sites and cultural artifacts.

Five years ago the Doğan News Agency reported that the submerged structure was set to become an underwater museum. Experts believe it was built in AD 390, to honor St. Neophytos, who was among the saints and devout Christians martyred during the time of Roman emperors Diocletian and Galerius.

Neophytos was killed by Roman soldiers in A.D. 303, a decade before an official proclamation permanently established religious toleration for Christianity within the Roman Empire, they say.

I thought to myself, ‘How did nobody notice these ruins before?’ said Prof Mustafa Sahin

Uludag University Head of Archaeology Department Prof Mustafa Sahin told the agency in 2015 the church was built in tribute to him, at the place where he was killed.

He said: “We think that the church was built in the 4th century or a later date.

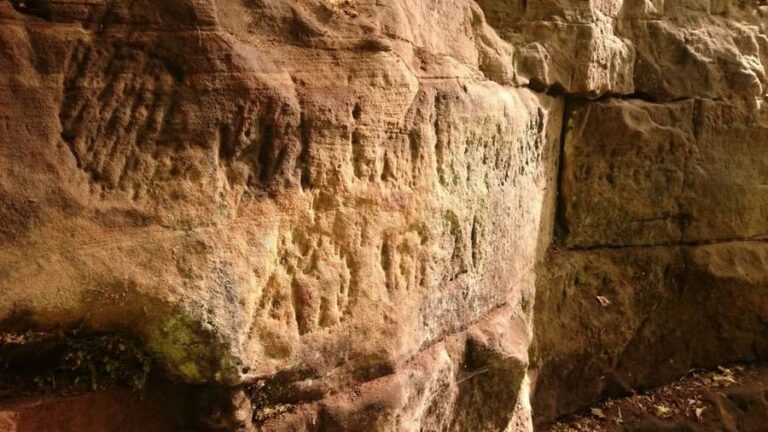

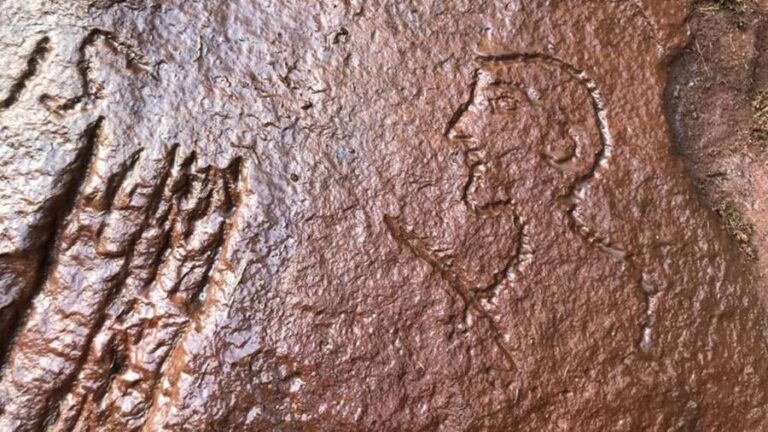

“It is interesting that we have engravings from the Middle Ages depicting this killing. We see Neophytos being killed on the lake coast.” Ancient resources show that Christians definitely stopped by Iznik in the Middle Ages while making their pilgrimage to visit the church.

“Rumour has it that people in Iznik were asking for help from the body of Neophytos when they were in difficulty,” Sahin said.

The researcher told Live Science that he had been carrying out field surveys in Iznik since 2006, and “I hadn’t discovered such a magnificent structure like that.

“When I first saw the images of the lake, I was quite surprised to see a church structure that clearly.”

He also told the Archaeological Institute of America: “I did not believe my eyes when I saw it under the helicopter.

“I thought to myself, ‘How did nobody notice these ruins before?’”

PAGAN TEMPLE?

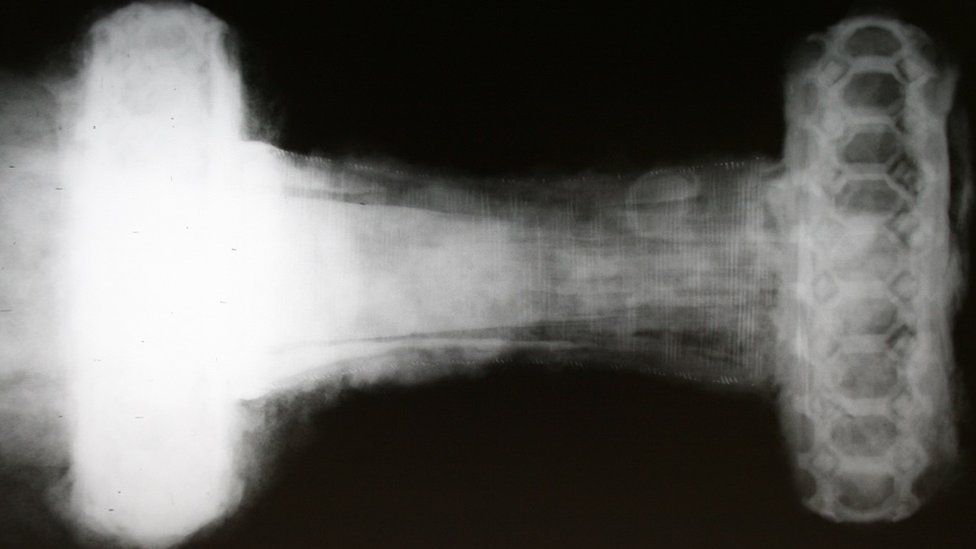

And, there might be a pagan temple beneath the church, reports The Weather Channel. Researchers have uncovered fragments of an ancient lamp and early coins from the reign of the emperor Antoninus Pius – indicating a more historic structure buried under the church.

Sahin said he believed the basilica could have been built on top of a temple to Apollo. The information shows there is a connection with the Roman emperor Commodus – to a similar temple at Iznik, then known as Nicea, outside the city walls.

“Could this temple have been underneath the basilica remains?” Sahin asked of the church, which is to be transformed into an underwater archaeological museum.

The early Byzantine-era basilica has architectural elements from the early period of Christianity and is situated 20 meters from the banks of Lake Iznik in the northwestern Turkish province of Bursa.

Archaeological finds excavated since 2015 include the memorial stamp of the Scottish knights, who were believed to have been among the first foreign visitors to the basilica, reports Daily Sabah.