5,000-Year-Old Tavern With Food Still Inside Discovered in Iraq

Archaeologists have unearthed the remains of an ancient tavern that’s nearly 5,000 years old in southern Iraq, the University of Pennsylvania announced last week.

The find offers insight into the lives of everyday people who lived in a non-elite urban neighborhood in southwest Asia around 2700 B.C.E.

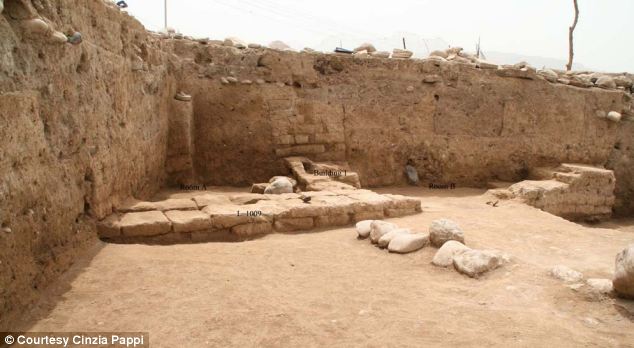

Inside the public eating space—which included an open-air area and a kitchen—researchers with the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Pisa found an oven, a type of clay refrigerator called a zeer, benches and storage containers that still held food.

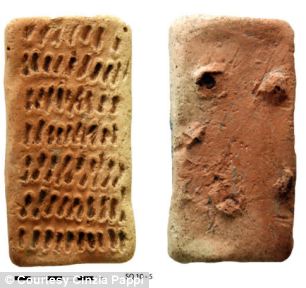

They also found dozens of conical-shaped bowls that contained the remains of fish, reports CNN’s Issy Ronald.

The tavern was discovered at Lagash, a 1,000-acre archaeological site that was a bustling industrial hub with many inhabitants during the Early Dynastic period. Researchers say Lagash was one of the largest and oldest cities in all of southern Mesopotamia.

“The site was of major political, economic and religious importance,” says Holly Pittman, an archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania and the Lagash project director, in a statement from the university.

“However, we also think that Lagash was a significant population center that had ready access to fertile land and people dedicated to intensive craft production.”

Researchers have been conducting the most recent round of Lagash excavations since 2019, but work at the site dates back to the 1930s. Over the past four years, researchers have used an array of high-tech techniques to better understand the site, including capturing drone imagery and conducting magnetometry analysis.

They’ve also collected and studied sediment samples from as deep as 80 feet below the surface to understand the site’s geological and geophysical evolution over the years.

“It’s not like old-time archaeology in Iraq,” says Zaid Alrawi, project manager for the Lagash project at the Penn Museum, in the statement.

“We’re not going after big mounds expecting to find an old temple. We use our techniques and then, based on scientific priority, go after what we think will yield important information to close knowledge gaps in the field.”

To investigate the ancient tavern just 19 inches below the surface, the archaeologists used a technique that involves excavating thin horizontal sections one by one. Discovering the tavern suggests that the society at Lagash included a middle class, in addition to enslaved individuals and elites.

“The fact that you have a public gathering place where people can sit down and have a pint and have their fish stew, they’re not laboring under the tyranny of kings,” says Reed Goodman, an archaeologist at the University of Pennsylvania, to CNN. “Right there, there is already something that is giving us a much more colorful history of the city.”

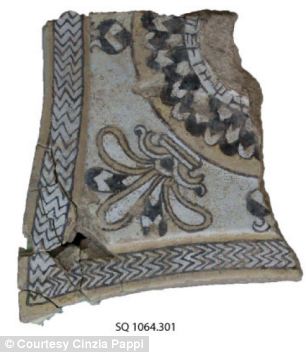

The researchers’ other discoveries at the site include an area where the city’s ancient inhabitants once made pottery, complete with six ceramic kilns, benches and a table. They also found a domestic dwelling that contained a toilet and a kitchen.

“As you excavate, you analyze and create a story that we hope gets closer and closer to the reality of the past,” says Alrawi in the statement.