9,000-yr-old Site near Jerusalem is the “Big Bang” of Prehistory Settlement

A huge 9,000-year-old Neolithic settlement — the largest ever discovered in Israel, say archaeologists — is currently being excavated outside Jerusalem, researchers said in mid 2019.

This site, located near the town of Motza, is the “Big Bang” for prehistory settlement research due to its size and the preservation of its material culture, said Jacob Vardi, co-director of the excavations at Motza on behalf of the Antiquities Authority, according to The Times of Israel.

Among the many important findings is that 9,000 years ago, the people of the settlement practiced religion. “They carried out rituals and honored their deceased ancestors,” Vardi, an archaeologist, told Religion News Service.

Perhaps 3,000 people lived in this settlement near where Jerusalem is today, making it quite a large city for the period that is sometimes called the New Stone Age. The site has “yielded thousands of tools and ornaments, including arrowheads, figurines and jewelry,” said CNN.”

The findings also provide evidence of sophisticated urban planning and farming, which may force experts to rethink the region’s early history, said archeologists involved in the excavation.”

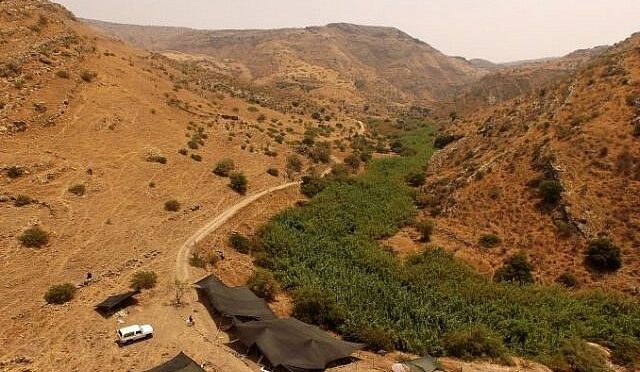

Although the area has long been of archeological interest, Vardi said the sheer scale of the site — which measures between 30 and 40 hectares — only emerged in 2015 during surveys for a proposed highway.

“It’s a game changer, a site that will drastically shift what we know about the Neolithic era,” said Vardi in an interview with The Times of Israel. Already some international scholars are beginning to realize the existence of the site may necessitate revisions to their work, he said.

“So far, it was believed that the Judea area was empty, and that sites of that size existed only on the other bank of the Jordan river, or in the Northern Levant. Instead of an uninhabited area from that period, we have found a complex site, where varied economic means of subsistence existed, and all this only several dozens of centimeters below the surface,” according to Vardi and co-director Dr. Hamoudi Khalaily in an IAA press release.

This site predates the first known settlement in Jerusalem by about 3,500 years. Experts had not thought that people lived in such a concentrated fashion during this time in the region.

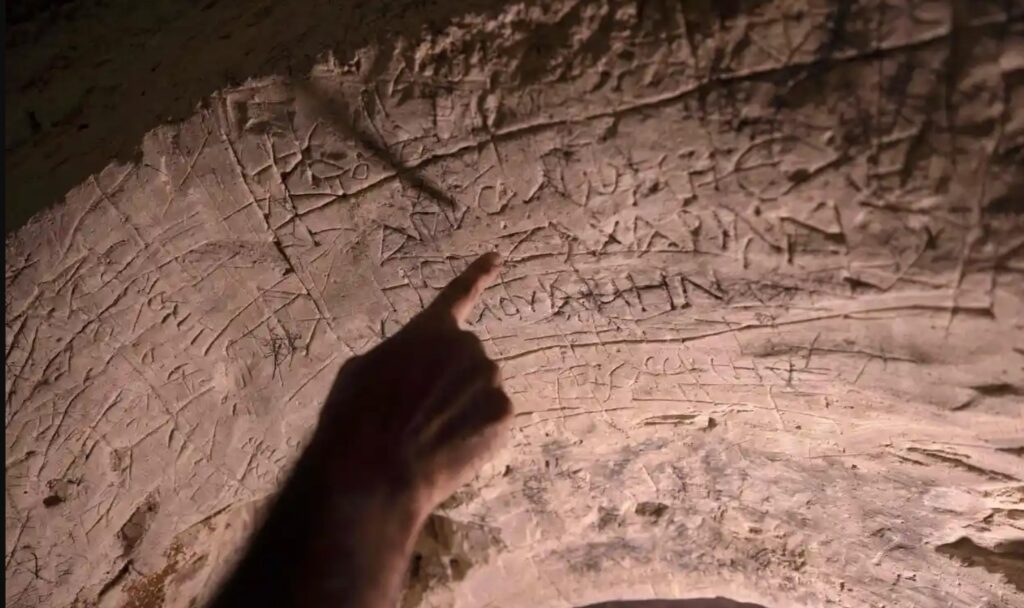

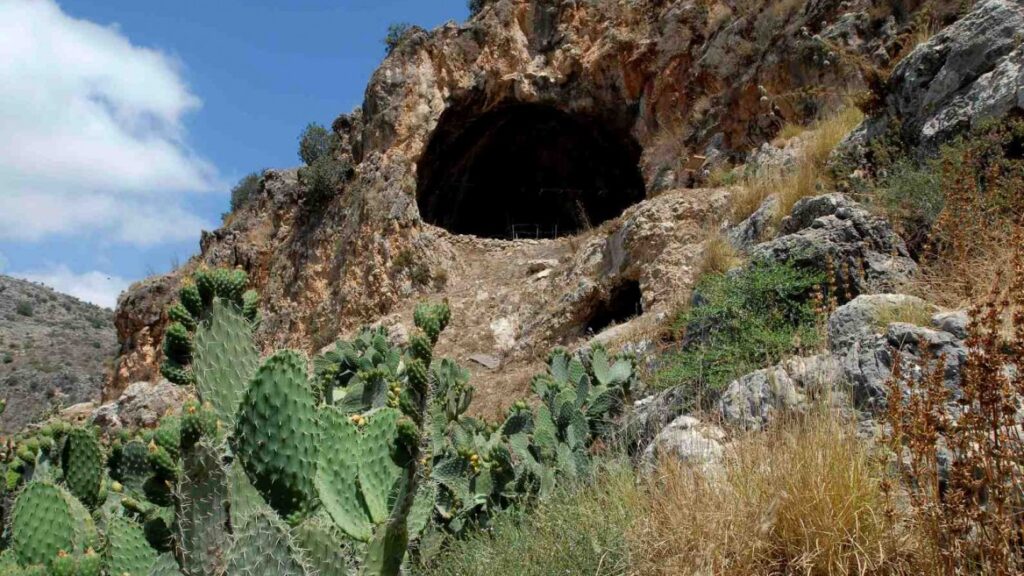

During the 16-month excavation, archaeologists discovered large buildings, separated by well-planned alleys, used for residential and public purposes. Some of the buildings contained plaster remnants.

Pieces of jewelry, including bracelets made of stone and mother of pearl, as well as figurines, locally made flint axes, sickle blades, knives, and thousands of arrowheads were also unearthed, said Religion News.

Vardi said the residents buried their dead with care in designated burial locations and placed “either useful or precious objects, believed to serve the deceased” after they died, inside the graves.

“We have decorated burial sites, with offerings, and we also found statuettes and figurines, which indicate they had some sort of belief, faith, rituals,” Vardi said. “We also found certain installations, special niches that might have played a role in ritual.”

Sheds held a large number of well-preserved legume seeds, something the archaeologists called “astonishing” given how much time has passed.

“This finding is evidence of an intensive practice of agriculture. Moreover, one can conclude from it that the Neolithic Revolution reached its summit at that point: animal bones found on the site show that the settlement’s residents became increasingly specialized in sheep-keeping, while the use of hunting for survival gradually decreased,” the antiquities authority said.