Fossilized Footprints Found in New Mexico Track Traveler With Toddler in Tow

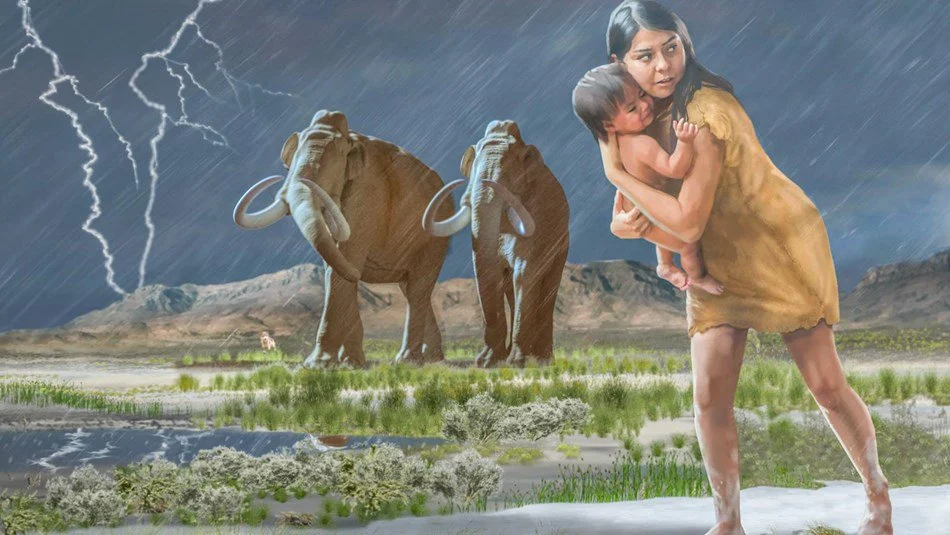

A small woman—or perhaps an adolescent boy—walks quickly across a landscape where giant beasts roam. The person holds a toddler on their hip, and their feet slip in the mud as they hurry along for nearly a mile, perhaps delivering the child to a safe destination before returning home alone.

Despite the fact that this journey took place more than 10,000 years ago, a new paper published in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews manages to sketch out what it might have looked and felt like in remarkable detail.

Evidence of the journey comes from fossilized footprints and other evidence discovered in New Mexico’s White Sands National Park in 2018, reports Albuquerque TV station KRQE.

Toward the end of the late Pleistocene epoch—between 11,550 and 13,000 years ago—humans and animals left hundreds of thousands of tracks in the mud along the shore of what was once Lake Otero.

The new paper investigates one specific set of tracks, noting details in the footprints’ shapes that reveal how the traveler’s weight shifted as they moved the child from one hip to the other.

“We can see the evidence of the carry in the shape of the tracks,” write study co-authors Matthew Robert Bennett and Sally Christine Reynolds, both of Bournemouth University in England, for the Conversation.

“They are broader due to the load, more varied in morphology often with a characteristic ‘banana shape’–something that is caused by outward rotation of the foot.”

At some points along the journey, the toddler’s footprints appear as well, most likely because the walker set the child down to rest or adjust their position. For most of the trip, the older caretaker carried the child at a speed of around 3.8 miles per hour—an impressive pace considering the muddy conditions.

“Each track tells a story: a slip here, a stretch there to avoid a puddle,” explain Bennett and Reynolds. “The ground was wet and slick with mud and they were walking at speed, which would have been exhausting.”

On the return trip, the adult or adolescent followed the same course in reverse, this time without the child. The researchers theorize that this reflects a social network in which the person knew that they were carrying the child to a safe destination.

“Was the child sick?” they ask. “Or was it being returned to its mother? Did a rainstorm quickly come in catching a mother and child off guard? We have no way of knowing and it is easy to give way to speculation for which we have little evidence.”

The fossilized footprints show that at least two large animals crossed the human tracks between the outbound and return trips. Prints left by a sloth suggest the animal was aware of the humans who had passed the same way before it.

As the sloth approached the trackway, it reared up on its hind legs to sniff for danger before moving forward. A mammoth who also walked across the tracks, meanwhile, shows no sign of having noticed the humans’ presence.

White Sands National Park contains the largest collection of Ice Age human and animal tracks in the world. As Alamogordo Daily News reports, scientists first found fossilized footprints at the park more than 60 years ago. But researchers only started examining the tracks intensively in the past decade, when the threat of erosion became readily apparent.

The international team of scientists behind the new paper has found evidence of numerous kinds of human and animal activity. Tracks testify to children playing in puddles formed by giant sloth tracks and jumping between mammoth tracks, as well as offering signs of human hunting practices.

Researchers and National Park Service officials say the newest findings are remarkable partly for the way they allow modern humans to relate to their ancient forebears.

“I am so pleased to highlight this wonderful story that crosses millennia,” says Marie Sauter, superintendent of White Sands National Park, in a statement. “Seeing a child’s footprints thousands of years old reminds us why taking care of these special places is so important.”