World’s Oldest Wine Found – Imbued with a Cremated Roman Aristocrat!

An extraordinary discovery was made in a Roman tomb in Carmona, Spain. Among the skeletal remains of six individuals, researchers found a glass funerary urn containing a reddish liquid. At over 2,000 years old, this liquid has been identified as the oldest liquid wine ever discovered, tracing its origins back to Roman Andalusia.

The identification process, led by Professor José Rafael Ruiz Arrebola from the University of Córdoba, revealed groundbreaking insights into ancient Roman funerary practices, not to mention wine preservation!

Identification of the Oldest Wine

The research team initially suspected the liquid might have been wine but needed to confirm this through rigorous chemical analysis. Conducted at the University of Córdoba’s Central Research Support Service (SCAI), the analysis, just published by the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, focused on various factors, including pH levels, absence of organic matter, and the presence of mineral salts and specific chemical compounds. Comparing these results with modern wines from Montilla-Moriles, Jerez, and Sanlúcar provided the first clues, reports The Guardian.

The definitive identification hinged on detecting polyphenols, biomarkers present in all wines. Using advanced techniques, the team identified seven specific polyphenols also found in contemporary wines from the same region.

The absence of syringic acid, a polyphenol found in red wines, indicated that the ancient wine was white. However, the researchers noted that the absence might also be due to degradation over time.

The Tomb and Its Inhabitants

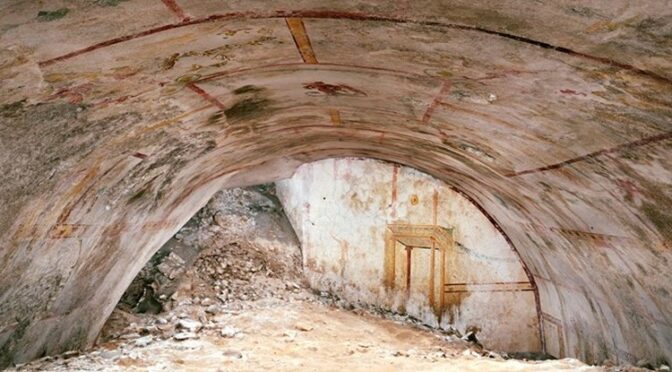

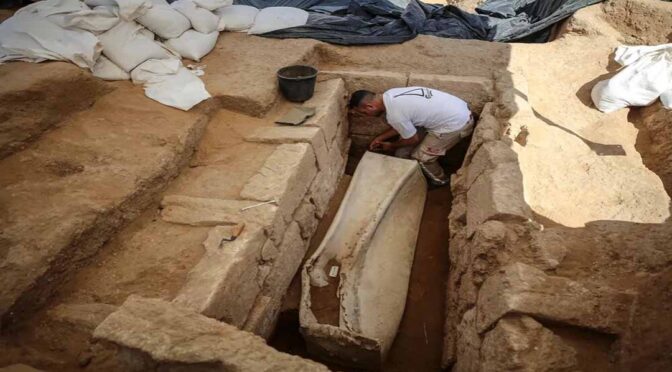

The tomb, a circular mausoleum, likely belonged to a wealthy family and was situated along the road connecting Carmo with Hispalis (modern Seville). The skeletal remains found within belonged to two men and two women, along with two others whose identities remain unknown.

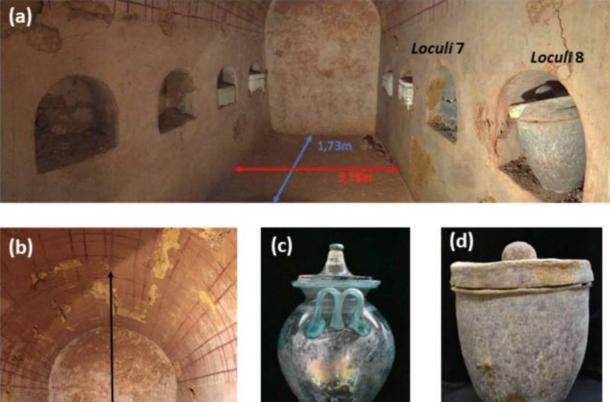

The preserved wine was found in the urn with one of the men’s cremated bone remains, highlighting a significant gender distinction in Roman funerary customs. Popsci explains that interring bones in an urn filled with wine was a popular burial ritual among the Roman elite.

In ancient Rome, women were generally prohibited from consuming wine, a practice reflected in the contents of the funerary urns. While the man’s urn contained wine, a gold ring, and bone fragments, the woman’s urn held amber jewels, a perfume bottle with patchouli scent, and remnants of silk fabric. These differences underscore the gender-specific rituals and societal norms of the time.

Insights into Roman Funerary Practices

The discovery of this ancient wine provides a rare glimpse into Roman funerary rituals and also sheds light on cultural and social aspects of ancient Rome. The inclusion of wine in the man’s urn suggests it played a symbolic role in his journey to the afterlife.

The exceptional preservation of the tomb was due to the sealed environment preventing contamination which has ensured the wine remained intact for millennia.

The identification of the wine’s origin, though challenging due to the lack of contemporary samples, was aided by the analysis of mineral salts in the liquid.

These salts were consistent with those found in modern white wines from the former province of Baetica, particularly the Montilla-Moriles region. This connection highlights the long-standing wine-making tradition in Andalusia and its historical significance.

The discovery of the world’s oldest wine still in liquid form in Carmona offers a tangible link to the past, providing insights into the lives and customs of the ancient Roman era.