Roman-era altar stone has been discovered under Leicester Cathedral

The base of a Roman-era altar stone has been discovered under Leicester Cathedral, the first Roman altar stone ever found in Leicester.

The area was previously believed to be a garden space in the Roman city, but archaeologists from the University of Leicester Archaeological Service (ULAS) uncovered the remains of a Roman building in the northwest quarter of the site. Inside the cellar of this building was the base of an altar stone.

This was not a plain subterranean storage room. The floor is concrete and the stone walls were painted. The quality of construction materials, the decorative paintwork and the presence of the altar indicates the room was a private shrine or otherwise devoted to religious worship.

The room dates to the 2nd century A.D. and was accessed by an external passageway with timber walls and a flagstone floor. The cellar was demolished and filled deliberately in the late 3rd or early 4th century.

The altar was found toppled face-down into the rubble layer. It was made of local sandstone from a quarry just one mile away and was decorated on three sides.

The back is plain, so it was probably originally placed against a wall. About half of it survives. Archaeologists estimate it would originally have been about two feet tall.

Mathew Morris, who led the dig, said the discovery of the Roman altar – the first to be found in Leicester – was “amazing”.

He added: “For centuries, there has been a tradition that a Roman temple once stood on the site of the present cathedral.

This folktale gained wide acceptance in the late 19th century when a Roman building was discovered during the rebuilding of the church tower.”

“Underground chambers like this have often been linked with fertility and mystery cults and the worship of gods such as Mithras, Cybele, Bacchus, Dionysius and the Egyptian goddess Isis.

Sadly, no evidence of an inscription survived on our altar, but it would have been the primary site for sacrifice and offerings to the gods, and a key part of their religious ceremonies.”

Leicester Cathedral was built in the heart of the medieval city at least as early as the 12th century and likely earlier than that.

The current building mostly dates to the 19th century when the church was extensively restored, but Leicester was a seat of a bishopric from 680 A.D. until the Saxon bishop was chased out of town by invading Danes in 870 A.D., so it’s likely there was a Saxon church predating the Norman cathedral.

As part of an ambitious restoration program complete with construction of a new Heritage Learning Centre, the old churchyard and gardens have been undergoing a comprehensive excavation since October 2021.

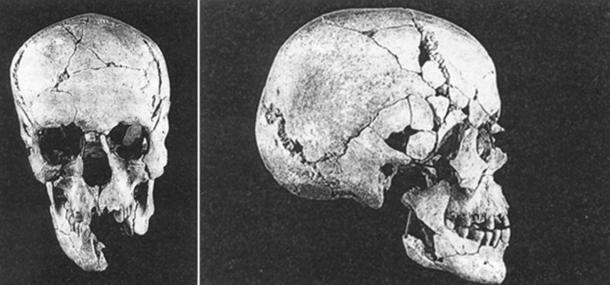

The excavation unearthed more than 1,100 burials dating from the end of the Saxon period in the 11th century to the middle of the 19th.

Radiocarbon dating of the earliest skeletal remains will narrow down the date range, and also confirm that the original parish church of St. Martin’s was founded in the late Saxon period.

The remains are currently undergoing examination that archaeologists hope will shed new light on the lives and deaths of Leicester’s inhabitants over nearly 1,000 years. When the research project is concluded, all of the individuals will be respectfully reinterred by Leicester Cathedral.

Archaeologists have also discovered the remains of a structure believed to be from the Anglo-Saxon period. If the date is confirmed, this will be the first Anglo-Saxon structure ever found in this area of Leicester.

It will expand the known map of Anglo-Saxon occupation of the town after the end of Roman occupation. A silver penny from the period (880-973 A.D.) found near the structure is the first Anglo-Saxon coin found in Leicester in almost two decades.