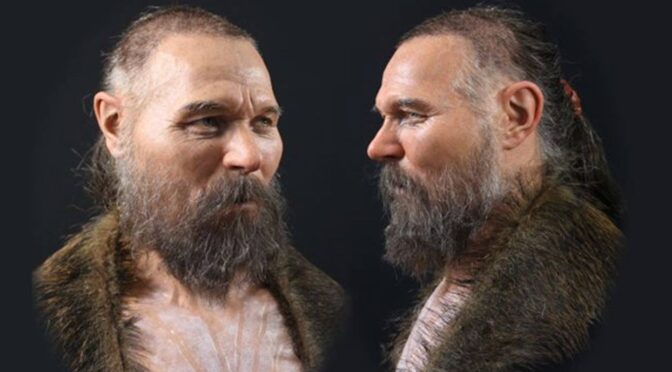

This is What a Man from the Tomb of Sunken Skulls Looked Like

When archaeologists were excavating a dry prehistoric lake bed in Motala, Sweden in 2009, they stumbled upon one of the most peculiar archaeological discoveries the nation had seen – the so-called ‘Tomb of the Sunken Skulls’, a collection of skulls dating back 8,000 years, which had been mounted on stakes. Now one of these skulls has been reconstructed to reveal the image of a man who met his fate at the gruesome archaeological site.

The Tomb of the Sunken Skulls

The Tomb of the Sunken Skulls is located on the eastern shore of Lake Vättern in the south eastern corner of Sweden. In 2009, a new railway line was to be built over a site known as Kanaljorden, where there once was a shallow lake.

Before construction could commence, however, an excavation had to be conducted on the dry riverbed to determine if anything archaeologically important was buried beneath it. What the archaeologists found was a mysterious site dated back to Sweden’s Mesolithic period.

Archaeologists were understandably surprised when they uncovered the skulls and skull fragments of up to 11 individuals, including men, women, children, and even infants.

Two of the human skulls –one fully intact and the other broken in half – were pierced with wooden stakes that protruded at the base of the cranium, while several others also showed signs that they had been treated in such a manner. Almost all of the adult skulls were jawless

The man behind the reconstruction is the forensic artist Oscar Nilsson, who has revealed the images of several other ancient people over the years. He explained the reasons behind many of his choices in reconstructing this man’s appearance.

For example, his wardrobe was based on faunal remains within the grave, “He wears the skin from a wild boar. We can see from how the human skulls and animal jaws were found that they clearly meant a big deal in their cultural and religious beliefs” Nilsson said.

The chalk design on the man’s chest, on the other hand, reflects the artist’s beliefs “It’s a reminder we cannot understand their aesthetic taste , just observe it,” he told LiveScience. “We have no reason to believe these people were less interested in their looks, and to express their individuality, than we are today.”

Rare Mesolithic Finds

The head of excavation for the Swedish heritage foundation Stiftelsen Kulturmiljövård Mälardalen, Fredrik Hallgren, said the skulls are the only known examples from the Mesolithic era . Hallgren also explained that most examples of this practice pertain to the historic period, in which colonial representatives mounted the skulls of murdered natives on wooden stakes.

Another interesting find was a female skull with another woman’s temporal bone stuffed inside it. Hallgren wonders whether the two women were close relatives, perhaps mother and daughter. The truth, however, will only be known through DNA analysis .

In addition to the skulls, archaeologists also found bones from other parts of the body, numerous animal bones, and tools made of stone, antler, and bone. The more noteworthy finds include a decorated pickaxe made from antler, bone points studded with flint, and animal remains that probably had a symbolic value to the people who used them.

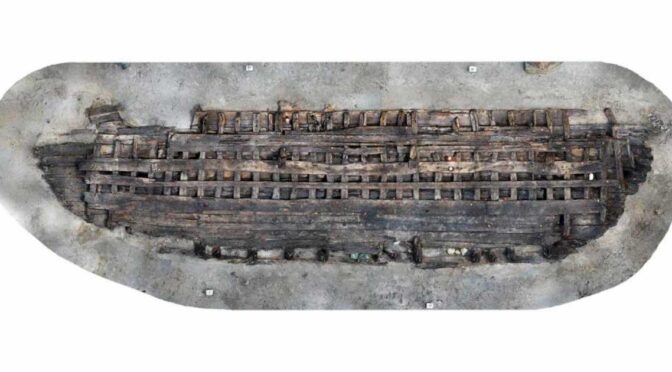

The artifacts were found to be laid out on a large stone packing, which is a type of mass grave encased in stone. This grave was built at the bottom of the shallow lake.

What Happened at the Tomb of the Sunken Skulls?

One plausible explanation for this curious site is that it was a ritual site which was used for secondary burials. According to this explanation, after the bodies of the dead decomposed, their bones were removed from their graves to be reinterred. Part of the ritual would have involved the display of the skulls, which is the function of the wooden stakes that were found protruding from the skulls found at Kanaljorden.

The pointed end of the stake was probably stuck into the ground, or perhaps into a bed of embers, as some of the skulls have slight traces of burning. After the ritual was complete, the remains were buried under the shallow lake (hence the name ‘Tomb of Sunken Skulls’). According to Hallgren, there is at least one other Mesolithic site in Sweden that bears traces of this tradition.

Another suggestion is that the skulls belonged to enemies killed in combat. According to this hypothesis, skulls were mounted on wooden stakes and brought back by warriors as war trophies . Scientific analysis would be able to help archaeologists gain a greater understanding of these remains.

Isotope analysis, for instance, would reveal whether the dead were from the local area or a distant place, while DNA analysis could inform whether the dead were related or not. So far, the researchers have obtained DNA data from six of the nine skulls and determined the skin , hair, and eye color of those individuals.

Based on isotope analysis, it seems that fish was an important part of the diet of the people buried at Kanaljorden. In addition, big forest game, such as red deer and elk, were hunted, based on the animal remains found at the site. Thus, it has been speculated that the society responsible for the burials at Kanaljorden were a nomadic people, and that the site was a sacred meeting spot.

For the most part of the year, the hunter-gatherers would be living in the surrounding areas, but they gathered at the rapids of the nearby river Motala for communal fishing of spawning fish. It is perhaps during this time of the year that marriages, feasting, and funerary rites were performed.