The Ancient Mystery of the Dolmens of the North Caucasus

Scattered around in some previously inaccessible parts of Russia are some mysterious stone structures built by an ancient megalithic civilization that have endured centuries of both veneration and plunder.

If you ever travel to the North-West Caucasus, you might encounter some strange stone structures that look like miniature houses with round holes in their front walls.

These are the dolmens, ancient megalithic monuments that date back to the early Bronze Age, from the middle of the 4th millennium BC to the end of the 2nd millennium BC.

The dolmens are scattered across the region, from Abkhazia to the Taman Peninsula in an area of approximately 12,000 square kilometers (around 4650 square miles), and are known by the locals as “ispun”, meaning the “houses of dwarves”.

Around 3,000 such megalithic monuments are known in the North Caucasus, with more discoveries regularly happening. The area has the largest concentration of dolmens on Earth.

The construction is remarkable, with massive stone plates fit together without the use of mortar or cement, precisely interlocking via specially crafted grooves. Some joints are so tight that a knife blade cannot pass through.

In 2007, an attempt to reconstruct a dolmen using high-precision electric tools with stones from Gelendzhik’s destroyed structures fell short of the precision achieved by Bronze Age builders.

The dolmens usually consist of a chamber with a large roof slab and an access portal formed by projecting blocks from the side walls and the overhanging roof slab. Most dolmens have a square, semi-circular, or oval access porthole in the center of the façade, which is thought to have been used to place offerings or burials inside the chamber.

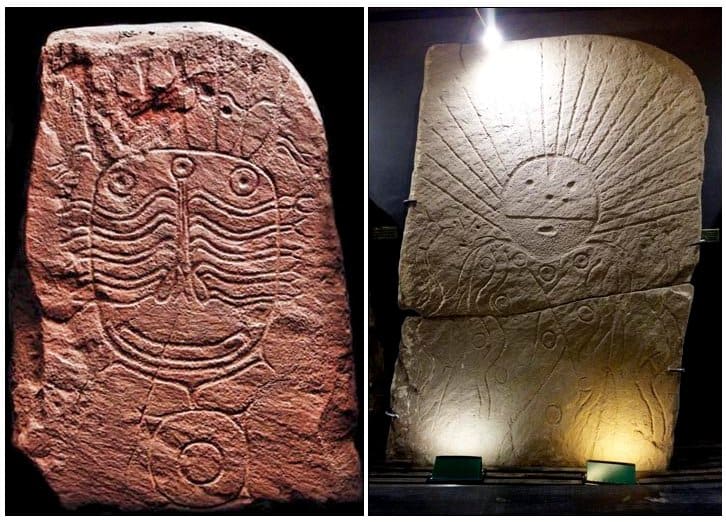

Some dolmens have raised patterns (petroglyphs) on their face slabs, such as vertical and horizontal zigzags, hanging triangles, concentric circles, and some depicting pairs of breasts.

These symbols may have had religious or cultural meanings for the builders, but their exact interpretation is still unknown. The dolmens were mainly constructed from fluidogenic rock masses, such as sandstone or limestone, which were hand-carried from nearby quarries to the construction sites.

The purpose and function of the dolmens are still debated by scholars. Some of the dolmens are aligned with astronomical phenomena, such as solstices or equinoxes, indicating that they may have had an astrological or calendrical function.

Some of them are clustered in groups or rows, suggesting that they may have marked territorial boundaries or sacred landscapes. Some of them contain human remains or offerings, indicating that they may have been used for funerary or ceremonial purposes.

The proponents of the theory that the sites were used for tribal worship or ritual ceremonies point out that some dolmens are located in remote areas or on hilltops, away from settlements or cemeteries, and that some dolmens have no traces of burials at all. They also suggest that the petroglyphs may have represented deities or ancestors that were revered by the Dolmen builders.

The identity and origin of the Dolmen builders are also unclear. Some propose that they were associated with the Klin-Yar community in the North Caucasus, or the Koban culture from the Great Caucasus Range.

Others suggest that they were a separate group of people with their own unique culture and traditions. The dolmens may have been built by different tribes or clans over a long period, reflecting their social and political organization.

The dolmens are an enigmatic and fascinating part mysterious prehistoric civilization that left behind these impressive stone monuments. They are also threatened by natural erosion and vandalism, of the Caucasus heritage, revealing glimpses of looting, and urban development.

Many dolmens have been damaged or destroyed over time, and some have been moved or reconstructed for tourism purposes. Efforts are being made to preserve and protect these ancient structures, which are part of the cultural and historical legacy of the region.