Inside mysterious woodland cave where Neolithic axe was found

Cornwall is well-known for its rugged sea caves, many of which are steeped in legends or stories of smuggling. But there is a remote cave, hidden in a valley far from the sea that is, perhaps, less well-known despite its intriguing history.

Almost a mile inland from the sea caves at Porthcothan Bay, lost in the dense foliage on the steep hillside of a woodland valley, there is a mysterious cave known locally as ‘Long Vugha’ or ‘The Vugha’.

Its small entrance, surrounded by brambles and moss and just big enough for a person to squeeze through, would be easily missed by anyone who was not searching for it and the vast cave that lies within.Clearly marked on the 1888 Ordnance Survey map as a ‘Fogou’, the name given to Cornwall’s ancient underground dry stone structures, there has been some debate about the age of this cave, and whether it is man-made or natural.

This is compounded by the evidence inside the cave that it has been shaped by tools, and the discovery of a Neolithic axe at the site.

The first mention of the Porthcothan cave in print was in 1754, when William Borlase described the site as a ‘Vugha’ in his book, ‘Antiquities Historical and Monumental of the County of Cornwall’.

Vugha is the Cornish word for cave, and it is thought to be the word from which ‘Fogou’ derived, which could go some way to explaining why it was marked as such in the late 19th century.

The long walk from Porthcothan to the cave crosses a stunning packhorse bridge, built in the first half of the 19 century by a man called Copplestone Cross.Whilst living at the nearby Porthcothan Mill, Copplestone also built Trevethan House, adding onto the existing Trevethan Farm. It is stories of the cave’s association with Trevethan Farm that offers us one of its most intriguing histories.

In Elizabeth Dale’s blog about Copplestone Cross’ packhorse bridge, she includes this quote from John Lloyd Warden Page’s 1897 book ‘The North Coast of Cornwall Its Scenery, Its People, Its Antiquities and Its Legends’:

“We come to Port Cothan a knot of cottages at the head of a cove, the sands of which are wet with the waters of a stream coming down the wild half-wooded valley behind. It is up or rather off this valley that we shall find the principal object of interest about Port Cothan. This is a Smugglers’ cave from which it would appear that the little hamlet was not as innocent in the “good old times” as it is now.”

The difficult clamber through dense woods on the way to the Vugha does not seem to lend itself to smuggling, but it is certainly out of the way.Detailed in the Trevethan family history, Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould’s account of Porthcothan cave in his 1899 ‘A Book of the West’ gives us this description: “About a mile up the glen that forms the channel through which the stream flows into Porth Cothan, is a tiny lateral combe, the steep sides covered with heather and dense clumps and patches of furze.”

At the end of a steep, muddy and overgrown path, rising out of the woods, the entrance to the cave would be easy to overlook.And yet, it has never been forgotten, featuring in Cornwall guides and history books for the past two and a half centuries, and even as a postcard in 1910.

For anyone like myself who gets claustrophobic, the thought of squeezing through the small hole into the darkness is daunting.

Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould’s account continues: “Rather more than half-way down the steep slope of the hill is a hole just large enough to admit of a man entering in a stooping posture. To be strictly accurate, the height is 3ft. 6in. and the width 3ft. But once within, the cave is found to be loftier, and runs for 50 feet due west, the height varying from 7ft.6in. to 8ft.6in., and the width expanding to 8ft.3in.”

Sure enough, as your eyes adjust, looking into the darkness of the cave, it is possible to see just how vast it is.The Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly’s Historic Environment Record describes its measurements as: “about 15m long, 3.0m high, around 2.0m wide at floor level, and smoothly triangular in cross-section.”

At this time of year, it is impossible to access the Vugha without crawling through a large puddle. But having made it through the water, the height of the cave rises quickly and it is possible to stand up.

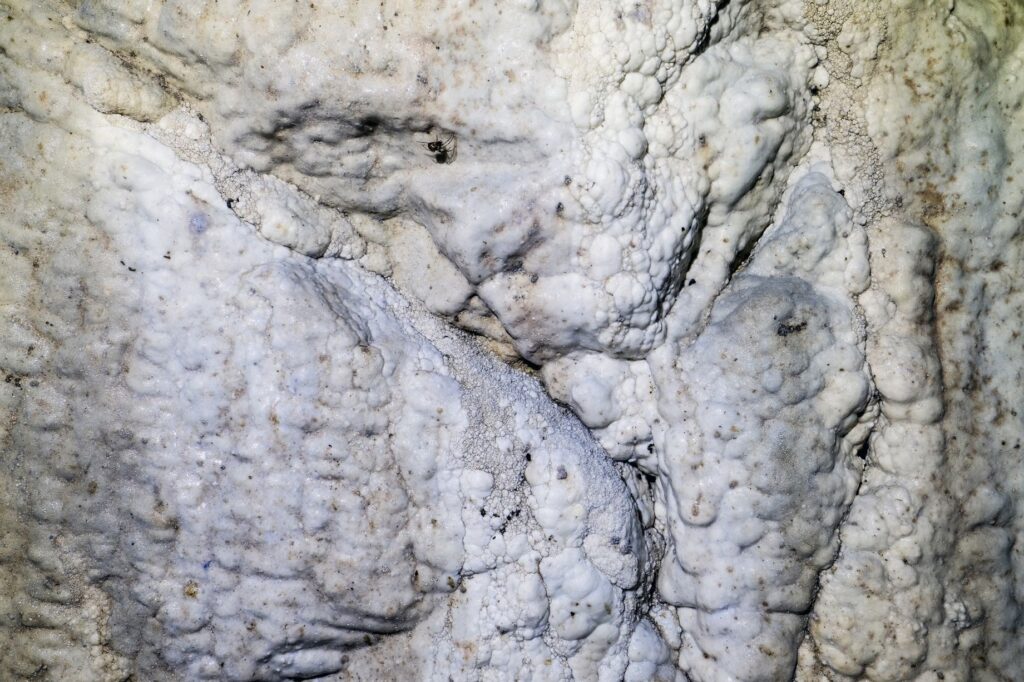

Unsurprisingly, inside the cave it is very dark. But by using long exposures and a flash, it is possible to see the smooth walls that are white in many places with the calcium in the water dripping through the limestone.

This amount of this white layer on the walls, known as travertine, helps to date the cave, as The Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly’s Historic Environment Record explains:“Layers of travertine have been deposited over the roof and walls, and also over the floor in some places, indicating that the cave must be quite ancient, though it is clearly an excavated feature and not a fogou.”

With a long exposure photo and some added light, it is possible to see just how white the walls have become at the rear of the cave.It is here that it is possible to see pick marks in the rock, showing that this natural cave has been extended and shaped by man at some time in the past.The Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly’s Historic Environment Record note that: “Traces of tool marks visible over much of the interior indicate that it has been shaped with sharp metal picks.”However, historian Howard Balmer from Porthcothan wrote a detailed article in Meyn Mamvro on The Vugha in 2003, suggesting that the pick marks were prehistoric, and that the impressive acoustics inside the cave could have been an important attribute for people in that era.This theory sits well with the Neolithic flint axe which was found at this site, and is now on display in the Royal Cornwall Museum in Truro.

Standing at the back of the cave, looking towards the small entrance some 15 metres away, it feels like being inside the belly of a huge whale.Every drip from the ceiling echoes loudly as it splashes on the wet floor.Bats are known to use this cave, although all I saw in the darkness were spiders.It is said that Long Vugha was used by the Home Guard in World War Two. And as a hideout for Royalists escaping from Sir Thomas Fairfax in the 17 century Civil War.The Trevethan family history speculates that, with the cave being on their land, it was most likely family members who were hiding in there in March 1646.

The popular theory of this curious cave’s history is that it was naturally formed, but then enlarged and shaped by man at some point, for some reason.

The Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly’s Historic Environment Record states: “It seems likely that it was originally a much smaller natural cave which has been excavated and enlarged, probably in medieval or post medieval times.”But was smuggling the real purpose for it?

On his visit in the 1800s, Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould noticed: “Immediately within the entrance may be observed notches cut in the rock, into which a beam might be thrust to close the mouth of the cave, which was then filled in with earth and bramble bushes drawn over it, when it would require a very experienced eye to discover it.”

He says that he found an old lady in the village who confirmed this, saying that her father “minded well the time when the Vouggha was filed with casks of spirits right chuck-full.”

Heading back to the opening of the cave, there is a small chamber off to the left. Small enough to squeeze into, but not high enough to stand in, and going back a couple of metres.It seems in the time of Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould’s visit, this chamber went back further, and was a clue to the cave’s secret history:

“At 7 feet from the entrance a lateral gallery branches off to the right, extending at present but 17 feet, and of that a portion of the roof has fallen in. This gallery was much lower than the main one, not being higher than 3 feet, but probably in a portion now choked it rose, at all events in places, to a greater height.

“This side gallery never served for the storage of smuggled goods. It was a passage that originally was carried as far as the little cluster of cottages at Trevethan, whence, so it is said, another passage communicated with the sands of Porth Mear.

“The opening of the underground way is said to have been in a well at Trevethan. But the whole is now choked up. The tunnel was not carried in a straight line. It branched out of the trunk at an acute angle, and was carried in a sweep through the rocks with holes at intervals for the admission of light and air.

“The total length must have been nearly 3500 feet. The passage can in places be just traced by the falling in of the ground above, but it cannot be pursued within.”

So, was The Vugha a natural cave, enlarged by smugglers to become a vast storage space, and connected to the well at Trevethan Farm by a 3500ft tunnel which has since collapsed?Or does its history extend much further into the past, to prehistoric times in Cornwall?The people who know the answer, would have once stood outside the front of this cave and looked at the same view.But for now, their secrets remain inside The Vugha.