Holding Cell for Gladiators, Doomed Prisoners Found at Roman Amphitheater in England

Archaeologists say that the amphitheater in Richborough, Kent, could hold up to 5,000 spectators who cheered on charging gladiators and roaring wild animals in epic fights.

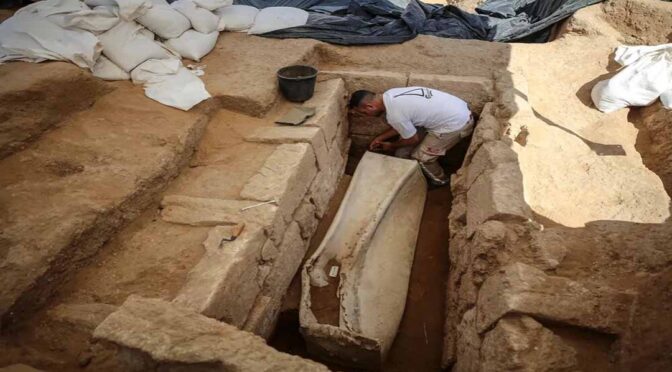

Today, the Roman-era amphitheater in Richborough, Kent, blends into the landscape. But it was once the site of violent gladiatorial combat, and archaeologists with English Heritage have just come across a holding cell, called a “carcer,” where gladiators waited to fight.

“The discoveries we’ve made during the excavation at Richborough are startling and exciting, and dramatically transform our understanding of the structure of the amphitheater and the nature of adjacent settlement in the town,” said Paul Pattison, English Heritage senior properties historian.

Researchers have known about the amphitheatre since 1849 when Victorian archaeologists discovered it. But the most recent examination of the site revealed a cell within the arena.

With walls more than six feet tall, the cell once held “those who entered the arena to meet their fate, whether wild animals, criminals, or gladiators,” according to English Heritage.

Though much is unknown about the amphitheater, its chalk and turf construction suggests it was built around the 1st century when Romans first invaded Britain. At its peak, it would have been an impressive sight: Archeologists found surprising traces of “vivid” red and blue paints on its interior walls.

“The evidence of painted decoration we have found on the arena wall, a unique find so far in amphitheaters in Britain, is remarkable, and a wonderful reminder that aspects of Roman culture abroad were also a feature of life in Roman Britain,” explained Tony Wilmott, senior archaeologist at Historic England.

Wilmott noted that the amphitheater could probably hold about 5,000 spectators, who — just like in Rome — descended to watch bloody gladiator fights. Sometimes, these fights pitted gladiators against each other. Other times, in especially violent battles called venationes, prisoners or gladiators fought against wild animals like lions and bears.

The mere existence of the amphitheater speaks to Richborough’s important place in the Roman Empire. Then called Rutupiae or Portus Ritupis, the settlement likely existed from the 1st to the 4th century, or as long as the Romans occupied Britain. It was said to be renowned throughout the empire for the quality of its oysters.

“As Richborough is coastal, it would have provided a connection between what was at the time called Britannia and the rest of the Roman Empire,” explained Pattison, noting that Richborough would have been unique and diverse.

“Because of that, all sorts of Romans who came from all corners of the Empire would have passed through and lived in the settlement.”

Alongside the carcer, archeologists found several artifacts that help paint a picture of life in Roman-era Richborough. They found coins, pottery, the bones of butchered animals, and jewelry.

Remarkably, archeologists also found the carefully buried skeleton of what appeared to be a pet cat.

Dubbed “Maxipus” by archeologists — after Russell Crowe’s character in The Gladiator — the cat was found buried just outside the amphitheater walls. It may have had nothing to do with the amphitheater itself but “appeared purposefully buried on the edge of a ditch,” according to English Heritage.

In addition, the most recent excavation also uncovered the puzzling remnants of two “badly burnt” and “bright orange” rectangular areas just outside the amphitheater.

“It is not yet known what function these buildings fulfilled,” noted English Heritage, “but it is possible they stood on each side of an entrance leading up to the seating bank of the arena.”

The fire that destroyed the structures, the organization said, “must have been dramatic.”

Now, Richborough’s amphitheater exists only as a circular field covered in grass. But, as the existence of the holding cell suggests, this part of the world once rang with thousands of screaming spectators, roaring animals, and charging gladiators.

English Heritage is hopeful to share it with the world. Following the end of their excavation, the on-site museum in Richborough will undergo a “major refurbishment and re-presentation.” It will open to the public in summer 2022.