Sweden’s Mysterious Shipwrecks Found Full of Medieval Household Goods

When underwater archaeologists discovered the sunken ruins of two medieval-era ships in Sweden’s Baltic Sea coastal waters last spring, they knew it would take some time to find answers explaining what the ships were and where they’d come from.

Those answers have perhaps come more quickly than expected, as the researchers examining the remains of the ships have now determined the ages of the vessels. These ships date to the 14th century, a time when the maritime-oriented Hanseatic League dominated the region commercially and politically.

According to a press release from the Scandinavian archaeological consulting company Arkeologerna, the key factor allowing for the discovery of this information was an analysis of wood samples taken from the wreck.

Dating procedures have revealed that the largest of the two vessels, which has been labeled Varbergskoggen 1, was constructed from wood that was harvested in the year 1346, or 676 years before the present.

The timber used to make the vessel was collected from quite a distance away, having been sourced from forests in the Netherlands, Belgium, and France.

Meanwhile, the second and smaller of the two ships, labeled the Varbergskoggen 2, was built from wood harvested in northern Poland sometime between the years 1355 and 1357.

Needless to say, the archaeologists were quite intrigued to find two ships sunk side by side that had come from entirely different places. It seems they sunk at the same time, victims of what at this time is an unknown event.

Why Did the Ships Sink? The Mystery is Still Open

The two merchant vessels were discovered during the construction of a rail tunnel near Varberg, approximately 120 miles (193 kilometers) north of Copenhagen, Denmark.

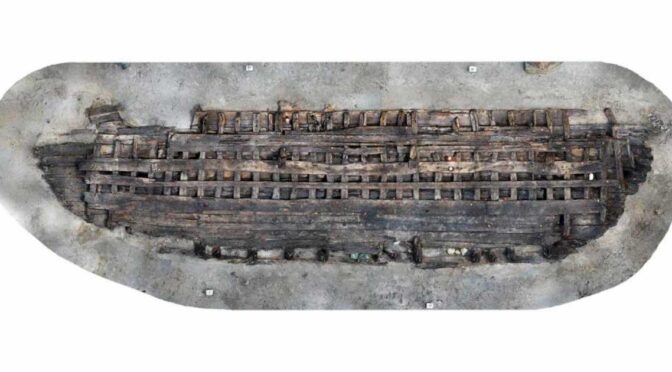

They are a common type of medieval ship known as cogs, which the Estonian Mere Museum website identifies as “large, with a spacious cargo space, and were mostly equipped with one mast and one large square sail.”

The Varbergskoggens 1 and 2 were located only 30 feet (nine meters) apart on the shallow coastal sea bottom, and that is something that archaeologists say almost never occurs. One of the wrecked ships had a nearly intact port site, and as of now is the most complete cog wreck ever found in Swedish waters.

Inside the wrecked ships underwater explorers found significant quantities of household goods. Among these discoveries were wooden spoons, engraved wooden kegs, and pairs of leather shoes.

All the items would have been moved to be sold or traded, and the researchers involved in studying the wrecks are hoping these goods will provide some clues to the ships’ destinations and missions.

Soil samples taken from the wrecked vessel may show what types of food were stored on the vessel. This information could also help researchers pin down the exact location where the ships were before they met their tragic demise.

Up to this point, the Arkeologerna archaeologists have been unable to determine exactly why the two ships sunk from examining their remains. Presumably both ships went down at the same time, if indeed they were traveling together at the time of the disaster.

The primary reasons why medieval ships sank would have been bad weather accompanied by high seas, collisions with other vessels or with submerged rocks along shorelines, flooding and shifting of poorly stored cargo, and possibly attacks by pirates (the latter was unlikely to have occurred in this instance).

In Swedish Waters, Shipwrecks Abound

This is just one of several ancient shipwrecks recovered off the coast of Sweden.

In 2012 in southern Swedish waters explorers found the remains of a 500-year-old ship that had been carrying soldiers and the Danish nobles they were guarding.

In October of this year, archaeologists announced that scuba divers had discovered yet another Swedish shipwreck. Timber samples revealed this to be the wreck of a 17th century warship known as the Äpplet, commissioned for battle by the king of Sweden.

Many of the sunken ships still undiscovered in this region are likely cogs, which adds to the urgency to find the ones that remain. From the 13th through the 17th centuries, the Hanseatic League, which consisted of cities from Scandinavia, Germany, the Netherlands, and Livonia, was active in trade throughout the Baltic Sea region.

Trading ships moved back and forth across the Baltic, connecting Hanseatic cities and settlements, and cogs were frequently the ship of choice for the members of the League.

Were flexible enough to be used as cargo vessels or warships. These sailboats were distinctive in appearance, with their giant square sales and single mast styling. They featured multiple structural anomalies that set them apart from other medieval sailing vessels.

Unfortunately, medieval vessels of this type were seldom preserved for long once they were off the water. That is why the shipwrecks found off the coast of Sweden have generated so much attention among archaeologists and historians who specialize in medieval Scandinavian history.