Viking Raids and Long-distance Oceanic Explorations Were All Enabled by Tar

What exactly inspired the 8th century Vikings of Scandinavia to sharpen their farming tools, to build ships and conquer Europe, has long been debated.

However, a new study all but closes the case book on this enduring mystery proving the industrial scale production of tar enabled the waterproofing of longships for long-distance raiding missions around Europe, across the Atlantic in North America and eastwards “Down the Russian rivers towards Islamic lands.”

Andreas Hennius of Uppsala University recently published his new findings in a paper titled Viking Age tar production and outland exploitation which can be read on Cambridge.org. He discovered “output from tar pits in Scandinavia increased dramatically just as Vikings began raiding other parts of Europe.”

The Viking Voyagers

Vikings were ruthless seafaring traders and fierce warriors who launched seaborne attacks on Europe from Scandinavia. By the mid-11th century the Viking’s Nordic empire expanded across vast territories in Britain, Iceland, Greenland and America, and as detailed in an article on History.com they also “raided Italian and Spanish ports and even attacked the walls of Constantinople.”

Hennius told reporters at The Guardian that his new research, which was funded by the Berit Wallenberg Foundation, reveals the tar pits “could produce 300 liters in one production cycle,” which would enable production of more than enough tar to waterproof a large fleet of ships.

“Tar production … developed from a small-scale activity … into large-scale production that relocated to forested outlands during the Viking period,” added Hennius.

Traditionally, archaeologists have proposed that changes in climate boosted agriculture, causing a sharp spike in population, which inspired the Vikings to look for new lands .

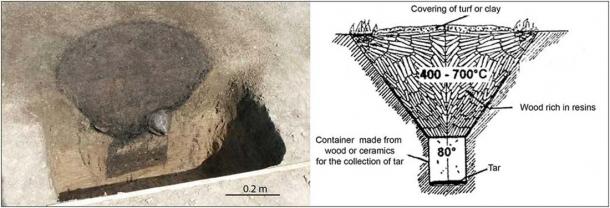

Others maintain local chieftains funded treasure hunting raids to further establish their wealth, dominance and power, but now, Hennius had proved that “tar has been used for millennia to waterproof boats. It was made in pits filled with pine wood, covered with turf and set on fire.

Small domestic tar kilns were found in Sweden in the early 2000s. These dated to between AD100 and 400. But much larger pits were found during road construction and dated to between 680 and 900, when the rise of the Vikings began.”

Tar Trade

The pits were, up to now, thought to have been used for producing charcoal, but Hennius argues that, “These kilns are not associated with any inhabited settlements and were situated closer to forests of pine, which was their key ingredient.”

Vikings then sailed their tar enhanced longships on long distance raids. The research paper also noted that, “This development coincides with Scandinavian society’s intensified marine focus and the introduction of the sail.

This most probably drove the increase in tar production, which was used for protecting wood, impregnating and sealing sails, and as a trade product.”

Viking raiding and trading was not confined to precious objects , metals, stones… and tar. A New York Times article dissing the 2014 Vikings: Life and Legend , exhibition at the British Museum, said “A slave collar from Dublin and an ankle shackle from Mecklenburg in Germany remind us that Vikings were very active slave traders, capturing adults and children in raids, both to sell them or to keep as domestic servants and laborers.”

Driven to Explore and Exploit

What is more, the same article reports eyewitness accounts from Arab travelers that speak of “Vikings transporting slaves down the Russian rivers towards Islamic lands.

And DNA evidence from Iceland suggests that while the males are almost all of Scandinavian origin, there is a significant element of Irish and Scots DNA among the females, most of whom probably arrived as slaves.”

And earlier this year, The Independant published an article about the findings of scholar Birgitta Wallace , an award-winning specialist in Norse archaeology and Viking evidence in the West, who uncovered evidence of the “long lost Viking settlement that featured in sagas passed down over hundreds of year,” on the east coast of Canada.

If Wallace is proved correct, it would be the second Viking settlement to be discovered in North America.

What is special about Andreas Hennius’ ‘tar pit’ discovery is that it is the scaffolding which underpins all of these recent discoveries of Vikings in exotic lands; for the fact is clear, without tar the Vikings wouldn’t have left the coasts of Scandinavia.