A “Made in China” Label Solved The Mystery of an 800-Year-Old Shipwreck

The practice of branding goods with their country of origin has been going on much longer than you might think – and a “Made in China”-style label etched into a 12th century piece of pottery has helped experts accurately date the cargo haul of a mysterious shipwreck.

Discovered in the 1980s by a fisherman in the Java Sea, off the coast of Indonesia, the wreck has been the subject of several studies since then. Archaeologists originally thought the ship set sail in the 13th century, but the new findings have them thinking again.

By analysing these ceramics and the rest of the goods on board – which include elephant tusks for use in medicine and art, and sweet-smelling resin for producing incense and sealing ships – researchers now have a better idea of how the sunken vessel fits in with the broader picture of China’s rich history.

“Initial investigations in the 1990s dated the shipwreck to the mid to late 13th century, but we’ve found evidence that it’s probably a century older than that,” says one of the team, Lisa Niziolek from the Field Museum in Chicago.

“Eight hundred years ago, someone put a label on these ceramics that essentially says ‘Made in China’ – because of the particular place mentioned, we’re able to date this shipwreck better.”

The inscription doesn’t actually say “Made in China”, though the intent is the same: to brand the ceramics with their place of origin. The label states the pots were made in Jianning Fu in the Fujian province of China.

Crucially though, it was renamed Jianning Lu after a Mongolian invasion dated to around 1278. That means the shipwreck may have happened earlier than that, and maybe as early as 1162, based on other tests.

It’s unlikely that ceramics like this would have been stored for very long, according to the researchers, so something carrying the old name would’ve been shipped off for sale pretty soon after it was made.

The team behind the study also looked at other pottery finds from the same era, and consulted with a variety of experts, to try and get a fix on when the ship might have set sail.

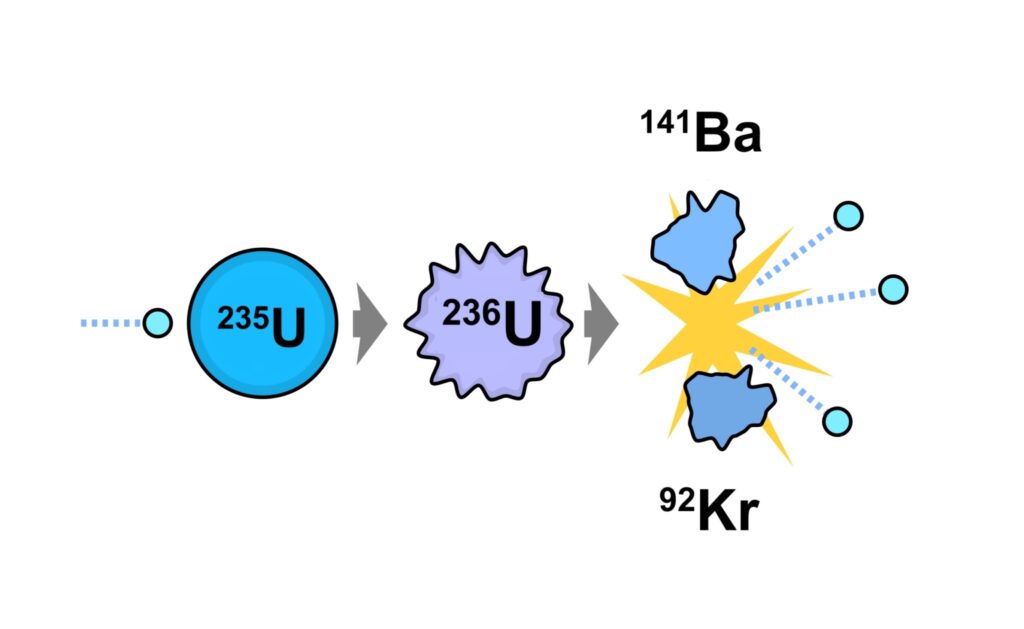

Carbon dating techniques can be applied to the tusks and the resin that were on board the ship, and these were initially used to identify the ship as being around 700-750 years old.

Since that analysis, we’ve got better at carbon dating, which is part of the reason for the re-evaluation. A new accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) test, together with the inscriptions on the the ceramics that we’ve already mentioned, suggests the shipwreck is indeed around 800 years old.

And that makes a big difference for archaeologists – the wreck marks a time when Chinese merchants began to be more active across worldwide maritime trade routes, switching from moving goods along the Silk Road to relying more on shipping. Pinning down that date is important for getting an accurate timeline for this period of transition.

It’s another example of how shipwrecks of any type can prove useful to historians, whether it’s to uncover the reading habits of pirates or the way that 17th-century royalty dressed.

“There’s often a stigma around doing research with artefacts salvaged by commercial companies, but we’ve given this collection a home and have been able to do all this research with it,” says Niziolek.

“It’s really great that we’re able to use new technology to re-examine really old materials. These collections have a lot of stories to tell and should not be entirely discounted.”