Galloway Hoard: Rare and unique Viking-age treasure goes on display at National Museum of Scotland

It was the day that an amateur metal-detecting enthusiast unearthed one of the largest discoveries of Viking treasure in Scotland.

In September , retired businessman Derek McLennan was scanning an area of church land in Dumfries and Galloway with two local ministers when he stumbled across more than 100 objects including solid gold jewellery, arm bands and silver ingots.

The artefacts, thought to have been buried between the mid-ninth and 10th century, included an early Christian cross made of solid silver, with unusual enamelled decorations.

At first, Derek failed to recognise the significance of his find.

However, to his amazement, the more he kept digging, the more he found.

After turning over what he thought was a silver spoon and wiping it with his thumb, he saw a saltire-type of design and knew instantly it was Viking.

“Then my senses exploded!” he revealed in an interview at the time, as further digging revealed a second layer of artefacts, including an intact Carolingian (western European) pot with its lid still in place.

In 2022, the treasure trove now known as the Galloway Hoard was acquired by National Museums Scotland for £1.98 million with the support of the National Heritage Memorial Fund, Art Fund and the Scottish Government as well as a major public fundraising campaign.

Since then, it has been undergoing extensive conservation and research at the National Museums Collection Centre in Edinburgh.

Now, this internationally significant collection is going on public display at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh for the first time, offering the chance to see intricate details hidden for over 1000 years, revealed by expert conservation, painstaking cleaning and cutting-edge research.

The new and free entry exhibition, Galloway Hoard: Viking-age Treasure, which opens on May 29, aims to transform visitors’ understanding of Scotland’s connections with the wider world during the Viking period, and to give a fascinating insight into archaeology in progress.

Amazing discovery and so much more

County Durham-raised professional archaeologist Dr Martin Goldberg, Senior Curator, Medieval Archaeology & History at National Museums Scotland, laughs that “diggers never find anything” when asked if he discovered anything of note during the 10 years he was a “jobbing archaeologist” in the early 2000s.

He’s delighted, however, to be working so closely with the Galloway Hoard which is the richest collection of rare and unique Viking-age objects ever found in Britain or Ireland.

Buried around 900 AD, as well as silver, gold and jewelled treasures, the hoard includes rarely surviving textiles including wool, linen and Scotland’s earliest examples of silk which raises intriguing questions about trade with Europe and Asia during the time the Vikings were known to be raiding, and settling, parts of Scotland.

“For me what’s amazing about the Galloway Hoard is it’s not just about that initial discovery – there were so many things in it there we’ve never seen before, and it had a very unusual preservation of organic materials,” he says.

“What the exhibition is trying to show people is the ongoing process of discovery that we’re engaged in.

“There are things with the conservation process – the cleaning and the preserving of the objects – that are being revealed to us for the first time, and probably the big icon of that is this Anglo Saxon cross that we are using as the marketing piece for the exhibition.

“Sure enough the 50 hours of conservation time it took my colleague Mary Davis to clean the cross has revealed this really stunning Christian iconography on it.

“That’s one of the unusual items – it’s the type of thing you wouldn’t expect in a stereotypical Viking hoard and at every turn when you look through this material, there is always something unexpected.”

Buried in layers

The exhibition shows how the hoard was buried in four distinct parcels.

The top layer was a parcel of silver bullion and a rare Anglo-Saxon cross, separated from a lower layer of three parts.

The first of these was another parcel of silver bullion wrapped in leather and twice as big as the one above.

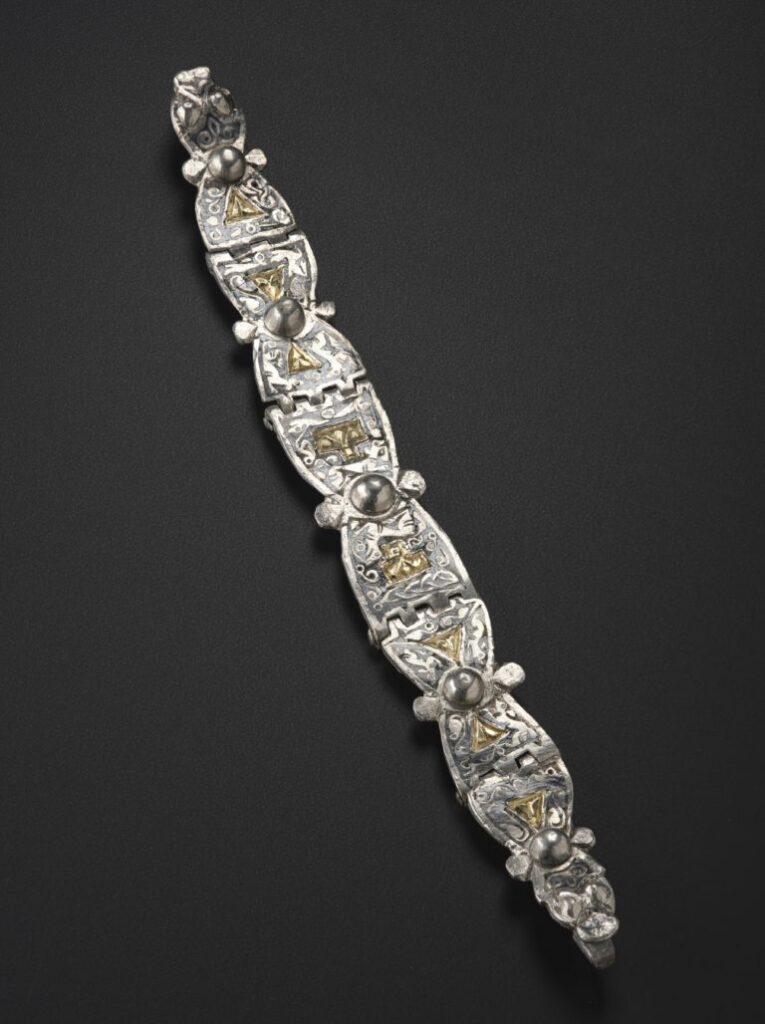

The second was a cluster of four elaborately decorated silver ‘ribbon’ arm-rings bound together and concealing in their midst a small wooden box containing three items of gold.

The third was a lidded, silver gilt vessel wrapped in layers of textile and packed full of carefully wrapped objects that appear to be have been curated like relics or heirlooms.

They include beads, pendants, brooches, bracelets, an elaborate belt-set, a rock crystal jar and other curios, often strung or wrapped with silk.

Martin explains that discovering and decoding the secrets of the Galloway Hoard is a multi-layered process.

Conservation of the metal objects has revealed decorations, inscriptions and other details that were not previously visible.

Research into many aspects of the hoard continues and will take many years.

Some items are too fragile to be displayed, particularly those with rare textile survivals.

The exhibition is using AV and 3D reconstructions to enable visitors to understand these objects and the work that is being done with them.

Comparison with other collections and consultation with specialists around the world has enabled deeper understanding of the hoard.

Yet at the same time, it raises many unanswered questions.

For example, an Anglo-Saxon runic inscription on an arm-ring fragment has revealed the name ‘Egbert’, perhaps a person associated with the hoard’s burial.

However, the Old English name, rather than a Scandinavian one, causes experts to question simple stereotypes about the identities of those involved with the hoard’s accumulation and burial.

Preliminary studies

Scientific analysis is enabling greater precision about the date and composition of the material, which in turn offers clues to where the individual objects may have come from.

A research programme funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, starting the Monday after the exhibition opens, aims to look into the origins of some of these materials.

Preliminary studies have already revealed incredible international connections with materials sourced from Ireland, England and Viking-age Scandinavia, as well as objects of some antiquity from ancient Rome, and others travelling thousands of miles from as far away as Central Asia.

The vessel in which the hoard was contained also appears to have originated somewhere in Central Asia.

“The silver bullion is part of an economy that has grown around the Irish Sea in the 9th century,” says Martin.

“There’s a sudden influx of silver and some of that silver is coming from as far away again as Asia, the Islamic Caliphates.

“We know that that material is being made in the Irish Sea but we know that the silver is coming from elsewhere.

“Say for instance if you find amber, that has to come from the Baltic, or the silk that’s in the hoard – we know that has to travel somewhere from Asia.

“You get this picture of regional economy through the silver bullion.

“But then the other materials that are unusual for a Viking hoard, and particular to this hoard, are telling us about much wider connections.”

Who did the hoard belong to?

Martin says it would be “pure speculation” to suggest who the hoard belonged to or why it was buried.

However, there is evidence of there being a group of people involved with some older objects looking like heirlooms passed down through generations.

“You get this picture of regional economy through the silver bullion.

“But then the other materials that are unusual for a Viking hoard, and particular to this hoard, are telling us about much wider connections.”

“There are runic inscriptions on four arm-rings, and those runic inscriptions would normally tell us that they are names, they are identifiers of people,” he says.

“Then there’s another group of arm-rings that are all sort of knotted together almost like a contract, but there’s four of them.

“So there seems to be these signals in various parts of the hoard that we are looking at four owners at least for the bullion.”

The Viking Age

Martin explains that the burial dates to the earliest part of the Viking age.

The first Viking attacks are recorded on Lindisfarne in 793 AD, and this hoard is probably buried 100 years after that around 900 AD.

For context, the first mention of the Gaelic kingdom of Alba is around 900 AD, while the first time that Alfred the Great’s descendants start talking about England as a political entity is when they are pushing back against the Vikings, and that’s also around 900 AD or certainly in the 10th century.

Martin says that while there isn’t a huge amount of material evidence of Viking activity in South West Scotland at this time, there is a lot of place name evidence all around the Irish Sea coasts where the seafaring Vikings raided, settled and then named settlements.

What a big find like the Galloway Hoard does is make archaeologists re-assess other evidence already linked to the area.

The Galloway Glens place name project, for example, is studying the interface between Brittonic, Anglo Saxon, Gaelic and Norse place names and trying to establish patterns left on the landscape.

It’s a “real challenge” for Martin to pinpoint a stand-out item because the hoard contains so many new things.

From the discovery of more gold than any other Viking age hoard that survives from Britain or Ireland, to the 5kg of silver and the mystery of the vessel from somewhere in Central Asia, there’s plenty to fascinate.

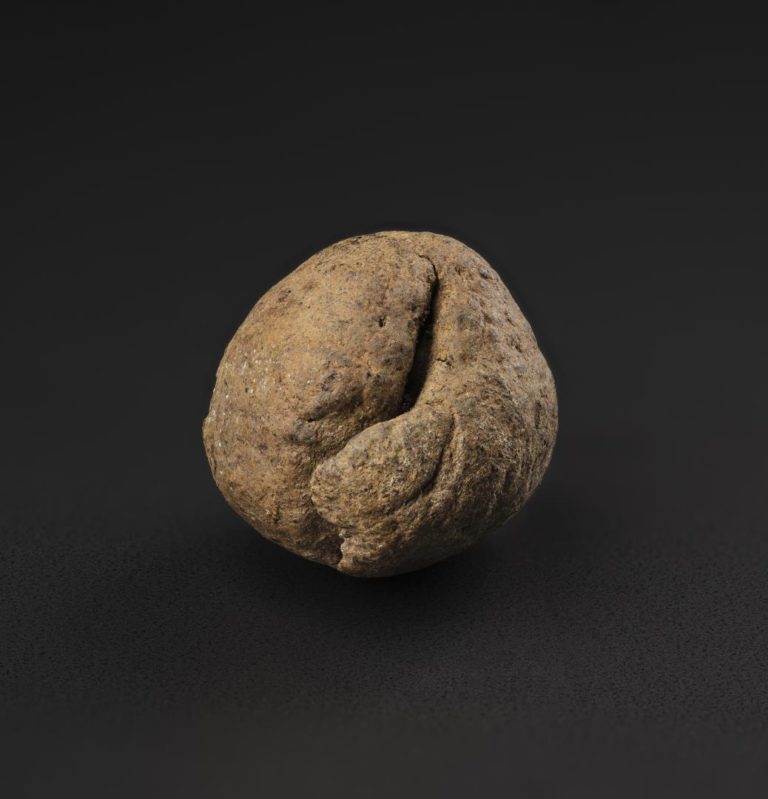

However, it’s two balls of dirt found right at the bottom of the vessel, nestled in amongst the silks and the gold and the rock crystal, that intrigue Martin most.

Normally they wouldn’t survive. They’d turn to dust, or if they got wet they would dissolve away.

But because the vessel had a lid on it and because the vessel was wrapped, they’ve been protected.

It also suggests the balls of dirt were curated – that somebody looked after them and somebody thought they were special enough to place in amongst all these treasures. The question is – why?

Stand-out item

“For me they stand out because they are so mundane,” says Martin.

“They are literally balls of dirt. You can see how they were formed as a kid would with Plasticine – like two sausages of dirt material being rolled into a ball about the size of a Malteser.

“But again my colleague Mary Davis who’s the conservator, she microscopically picked up traces of gold in the dirt and minute traces of bone. So you think, ‘right it’s not just any old dirt then!’

“It’s possible these were reliquary earth relics – balls of dirt rolled by people on pilgrimages to holy shrines then kept as sacred relics.”

It’s the solving of mysteries about the past that got Martin into archaeology in the first place, and he hopes visitors to the hoard, which he describes as an “incredible gift”, will be inspired by this ongoing process of discovery.