Remains of Man Who Was ‘Vaporized’ by Mount Vesuvius 2,000 years ago Discovered

The skeletal remains of a man whose flesh disintegrated in the heat from Mount Vesuvius almost 2,000 years ago have offered a new glimpse into one of history’s most famous volcanic eruptions.

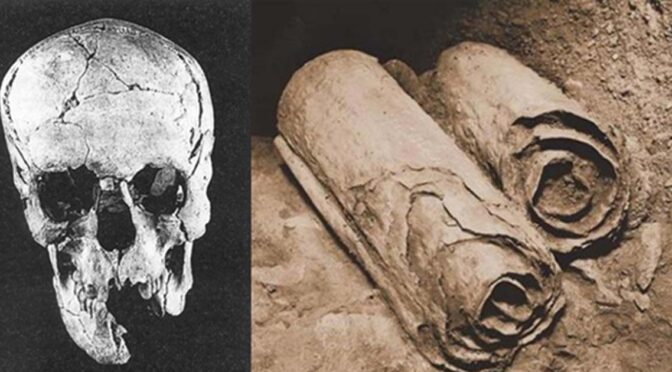

Archaeologists released pictures of the skeleton found at the ancient site of Herculaneum — which along with Pompeii was utterly destroyed by the eruption in 79 A.D. — the first human remains to be found there in decades.

The man, discovered in October and thought to be around 40 to 45 years old, was surrounded by carbonized wood. Preliminary work has also found traces of fabric and what appears to be a bag. Painstaking work is continuing to analyze the remains.

The bones were tainted red, a mark of the stains left by the victim’s blood, Francesco Sirano, director of the Herculaneum Archaeological Park, told the Italian news agency ANSA.

“It’s helped enormously to understand both the last moments of the site, but also the 100 years running up to it,” professor Andrew Wallace-Hadrill from the United Kingdom’s Cambridge University and a former director of the Herculaneum Project which collaborates on the ongoing excavations, told NBC News.

“The power of nature is absolutely awesome and to be under a volcanic eruption is just unimaginably violent. The site sits there peacefully in the sunshine and it seems so idyllic, and you have to explain to people that this has been through the most violent eruption.”

Wallace-Hadrill said that a previous excavation cut off the feet of the skeleton.

“Initially they found a couple of leg bones sticking out of the edge of the escarpment. And indeed the excavation through the escarpment had cut off the feet of this skeleton — a bit like finding a mafia killing,” he said.

The victims’ soft tissue was either vaporized in that heat or decayed over centuries. In one case, researchers said the heat was enough to vitrify the brain of a body in Herculaneum, turning it into a hard glass-like substance, as the temperature reached 968 degrees Fahrenheit.

Known as Ercolano in modern-day Italy and situated to the south of Naples, Herculaneum was a seaside town favoured by wealthy Romans. In 1709, ancient remains were revealed during the digging of a well. Previous excavations in the 1980s and the 1990s exposed more than 300 skeletons there.

Modern forensic techniques can reveal far more than previous generations of archaeologists could: Earlier this year, scientists said one skeleton found in the 1980s likely belonged to a Roman soldier sent on a doomed rescue mission to Pompeii and Herculaneum.

“You feel that you are in immediate contact with ancient life, not the blurred contact you get from typical archaeological sites. Because the process of destruction is 24 hours, you have this extraordinary immediacy,” Wallace-Hadrill said.

Pompeii and Herculaneum were situated in different directions from Vesuvius, meaning the effect of the eruption was different on both.

Wallace-Hadrill added that many of the people killed by the eruption — their charred remains often show them cowering for shelter — could have survived had they left the area.

“The wise ones, one realizes in retrospect, simply walked away from the eruption the moment it started,” he said. “If they’d all known this, they all could have escaped, they just had to walk away… But hundreds and thousands did not.”