Tragic remains of Pompeii child who tried to shelter from volcano found at ‘grand baths’

The bones of Pompeii child were discovered in the ruined building site of the city’s central baths where they sought shelter from Mount Vesuvius’ eruption.

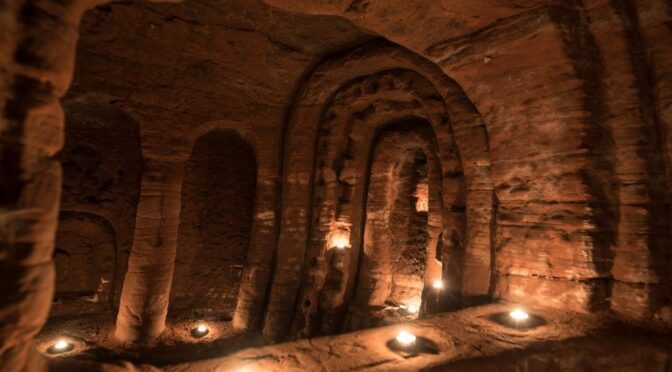

The magnificent spas were intended as a jewel in the crown of Pompeii, but were buried before they were completed by the volcano. The central baths were opened for modern visitors to the famous Roman town.

The marble pillars and blocks of the building remain where they were abandoned when the town was submerged in 79 AD by the pyroclastic flow from Vesuvius.

Archeological director of Pompeii, Massimo Osanna, told the AFP that the architects who designed the baths were inspired by Emperor Nero’s thermal bath in rome. The rooms were bigger and lighter here, with pools of marble, ‘ however he said.

The Central Baths lie in an area that has been restored as part of the so-called Great Pompeii Project, which began restoring the city in 2022 after the collapse of the 2000-year-old ‘House of the Gladiators, which had sparked worldwide outrage.

Archaeologist Alberta Martellone and colleagues analysed the skeleton of the child unearthed from the bathhouse, who is thought to have been around 8–10 years old. ‘It was an emotionally charged dig,’ said Dr Martellone. ‘He or she was looking for shelter and found death instead.’

‘[The excavation] was also moving from an architectural point of view, because it is unusual to find a building so large — with such ample rooms — in this densely built up city. It transmits a sense of grandiosity,’ she added.

The construction site with its small skeleton, she concluded, ‘is a sign of life interrupted, on more than one level.’

The city’s original public bathhouses were smaller, darker and often overcrowded and the new complex would have provided a more luxurious setting for all those who could afford it — most citizens, but not slaves.

Recent digs at Pompeii have offered up several impressive finds, including an inscription uncovered last year that proved the city near Naples was destroyed after October 17, 79 AD — and not on 24 as had previously been thought.

In October previous year, archaeologists discovered a vivid fresco- depicting an armour-clad gladiator standing victorious as his wounded opponent gushed blood — that had been painted in a tavern believed to have housed fighters and prostitutes.

Along with the newly-unearthed baths, visitors to Pompeii can now visit a small house sporting a racy fresco depicting the Roman god Jupiter, disguised as a swan, impregnating the Greek mythological figure of Queen Leda.

Across the cobbled Via del Vesuvio, the striking House of the Golden Cupids — believed to have belonged to the wealthy Gnaeus Poppaeus Habitus — has been reopened following renovation work on its mosaic floors.

While treasure hunters regularly pillaged Pompeii across the centuries — in hope of recovering precious jewels or valuable artefacts — whole areas have still yet to be explored by modern-day archaeologists.

Each discovery helps researchers understand not only what life was like in the ancient city, but also what happened in its dramatic final hours as the skies turned to fire and ash, Osanna said.

Although the partially EU-funded Grand Pompeii project will be winding up at the end of 2022, the Italian government will be providing 32 million euros (£27 million / $35 million) in order for digs at the ancient site to continue.

The ‘biggest challenge’ to preserving the vulnerable UNESCO world heritage site are the violent weather events being caused by climate change, Professor Osanna said.

The ruined city in southern Italy is the second most visited tourist site in the country — after the Colosseum in Rome — with just under four million visitors in previous year.