50 Roman Slaves Found Buried with Care at Roman villa in London

A burial ground for Roman slaves has been found near what was once a great ancient British villa. Many of the graves are very unusual and offer a glimpse of Rome ‘s impact on the culture and beliefs of the local Briton. This discovery also helps researchers understand better the existence of slavery in Roman Britain.

In Somerton, Somerset, southwestern England the cemetery was found. The site was uncovered by workers during the construction of a new school. They alerted the authorities concerned and the South West Heritage Trust investigated it.

Researchers found that it was a Romano-British cemetery dating back to the first century A.D. centered on the discovery of the fragments of pottery and coins. It was located near the outskirts of a large villa while in the city.

Strange Burials

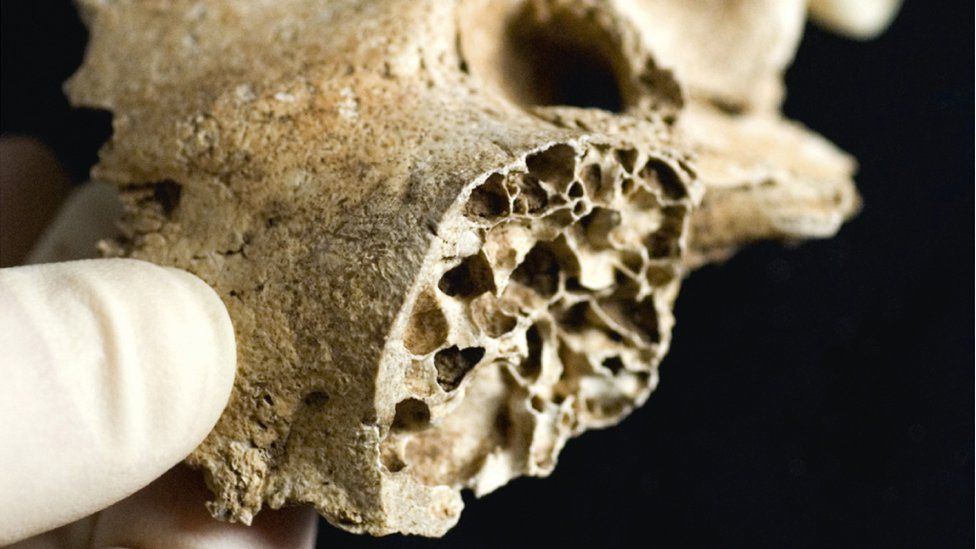

Altogether, approximately fifty Roman slave tombs were discovered and they varied considerably from the burial practices before the invasion. The deceased were placed in the ground with great care, in graves that were capped and sealed with slabs.

In one burial, these slabs were used to create a box-like feature, known as a cist, in which the dead person was placed before being buried. Steve Membery, who works with the South West Heritage Trust and who took part in the dig, told The Guardian that “they’ve actually built these graves. There’s been a lot of more care taken over these.”

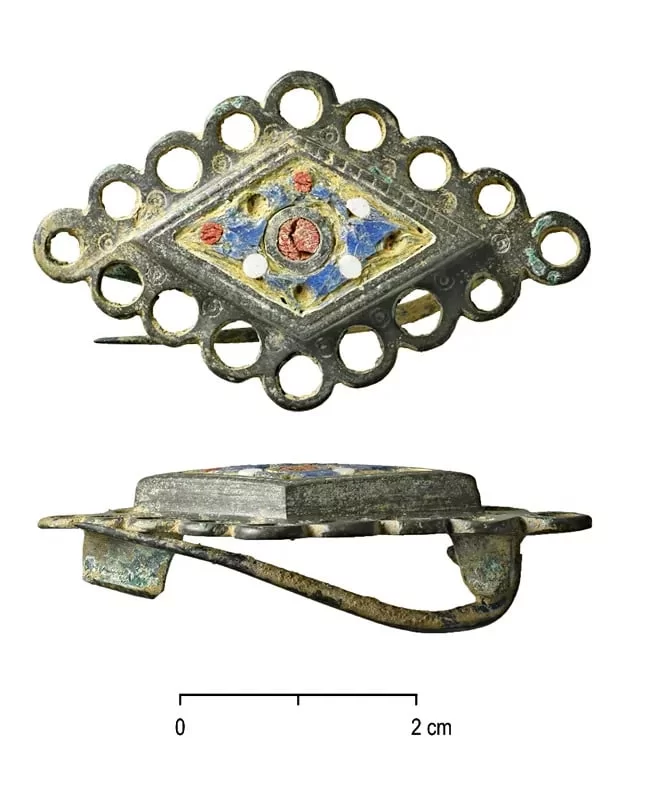

At first, the archaeologists believed that the dead were members of the local elite. This was on account of the great care taken over their burial and the fact that the cemetery was once near a villa complex. Moreover, the presence of grave goods, such as a coin from the reign of Emperor Vespasian would suggest that they were affluent during their lives.

It was initially assumed that the dead came from the villa and were members of the local Celtic population who had been Romanized.

The Graves of 50 Roman Slaves

Now it is believed that all of those buried in the cemetery were members of the lowest class. Membery, a historic environmental officer with the trust, told Live Science that “we are very confident that all the burials are people who worked on a Roman villa estate.”

They were almost certainly agricultural workers who labored on the estate of the villa owners. Some more may have been domestic servants in the villa.

The exact status of the dead is not known, but it is unlikely that they were paid for their work. Membery explained that “many may have technically been slaves,” according to BBC .

While others may have been dependent on their masters who lived in the villa and who had a status that was only a little better than that of slavery. In the Roman Empire , slavery was pervasive, and it took many forms and had different characteristics.

Insights into Ancient Roman Slavery

The fact that agricultural laborers and servants were buried with care and even grave goods, may tell researchers much about their lives. Clearly some people, possibly their family members, went to great efforts to see that they were given a decent burial.

Additionally, the grave goods found with some of them, indicate that the slaves may even have been able to accumulate personal wealth.

Some very small nails were found in a number of the graves. These are believed to have come from hobnailed boots, which long ago decayed in the earth. These boots would have been needed by slaves and others when working in the fields. This could indicate that, if as believed they were Roman slaves, their masters provided them with footwear and clothing.

A local representative Councilor Faye Purbrick told The Guardian that “we will be able to understand so much more about the lives of Roman people in Somerton thanks to these discoveries.”

The cemetery is providing researchers with a unique insight into the lives of Roman slaves. These discoveries reveal that their conditions may have been better than often assumed. All the retrieved artifacts from the Somerton site are going to be the subject of further scientific analysis.