Malta’s Hypogeum, One of the World’s Best Preserved Prehistoric Sites, Reopens to the Public

The complex of excavated cave chambers includes a temple, cemetery and funeral hall.

This month, one of the world’s best preserved prehistoric sites — a 6,000-year-old underground burial chamber on the tiny Mediterranean island of Malta — reopened to the public.

Last June, Hal Saflieni Hypogeum, one of Europe’s only known neolithic necropolises, closed for a series of improvements to its environmental management system. Its reopening brings updates that will enhance conservation and ongoing data collection while improving visitor access and experience.

Archaeological evidence suggests that around 4,000 BCE, the people of Malta and Gozo began building with the purpose of ritualizing life and death. The Hal Saflieni Hypogeum, one of the first and most famous of such complexes, is an underground network of alcoves and corridors carved into soft Globigerina limestone just three miles from what is now the capital city of Valletta.

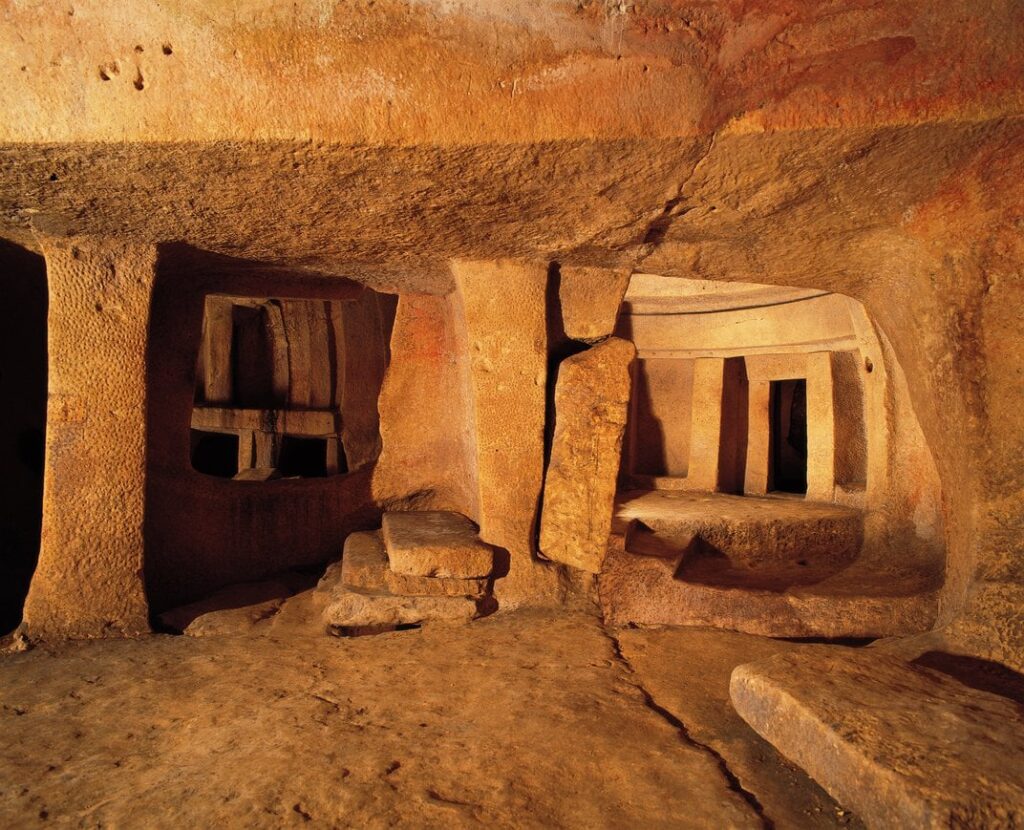

The builders expanded existing caves and over the centuries excavated deeper, creating a temple, cemetery and funeral hall that would be used throughout the Żebbuġ, Ġgantija and Tarxien periods.

Over the next 1,500 years, known as the Temple Period, above-ground megalith structures cropped up throughout the archipelago, many with features that mirror their subterranean counterparts.

Whatever remained of the above-ground megalithic enclosure that once marked the Hypogeum’s entrance was destroyed by industrialization during the late 1800s. Now, visitors enter through a modernized lobby, then descend a railed walkway and move chronologically through two of the site’s three tiers, glimpsing along the way evidence of the structure’s dual role as worship and burial place.

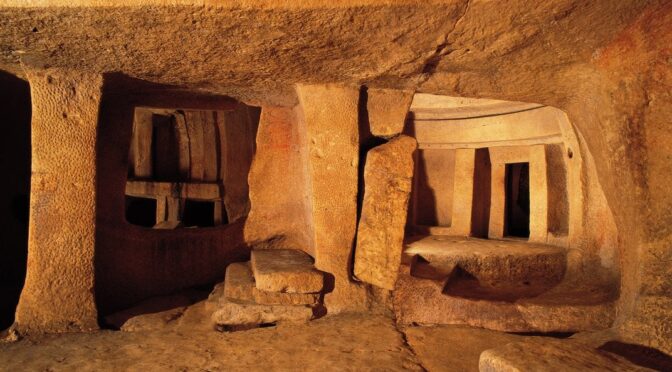

The Hypogeum’s oldest and uppermost level consists of a passageway, access to a cistern below, a courtyard-like space dug into the promontory and five low-roofed burial chambers carved out of pre-existing caves.

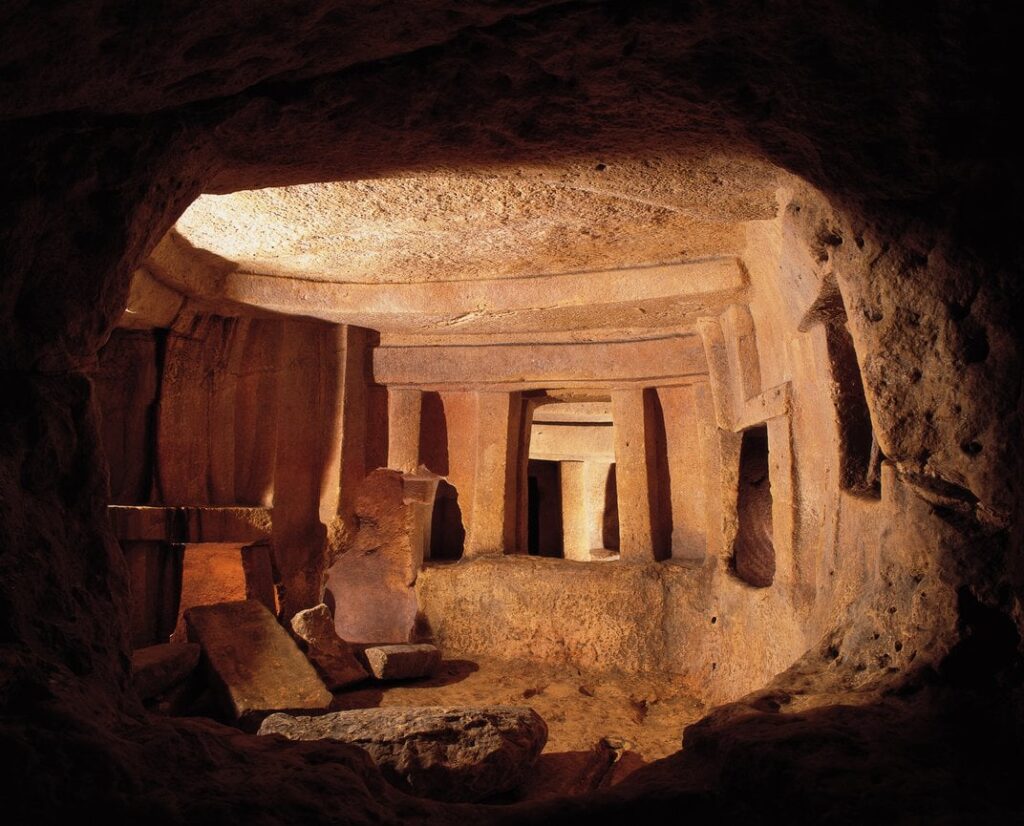

Archaeologists believe this is where funerary processions likely began, and Heritage Malta has kept an original grave intact. The middle level is the most ornate. It is also where archaeologists believe the bulk of ritual activity took place. In the “Oracle Room,” an oblong chamber measuring more than five meters long, niches in the walls create amplified and echoing acoustic effects, much like those at the Oracle of Delphi.

The “Holy of Holies” is carved to look like many of the Hypogeum’s contemporary above-ground temples. In front of its entrance, two linked holes in the ground may have been used to collect libations or solid offerings. Visitors exit via a spiral staircase before entering the Hypogeum’s youngest and deepest level.

The third tier reaches 10 meters into the earth and consists of five spaces, each less than five meters in diameter, that give access to smaller rooms that served as mass graves.

Like other megalith structures in Malta, the Hypogeum fell out of use by 2,500 BCE. The ancient necropolis wasn’t rediscovered until 1902, when construction workers accidentally found one of the chambers while excavating a well for a housing subdivision. It would be two more years before formal excavation took place and another four until the site opened to the public.

The Hypogeum provides insights into Malta’s Temple Culture and its contemporary above-ground structures. Archaeologists estimate over 6,000 people were buried at the site and have found beads, amulets, intricate pottery and carved figurines alongside the bones.

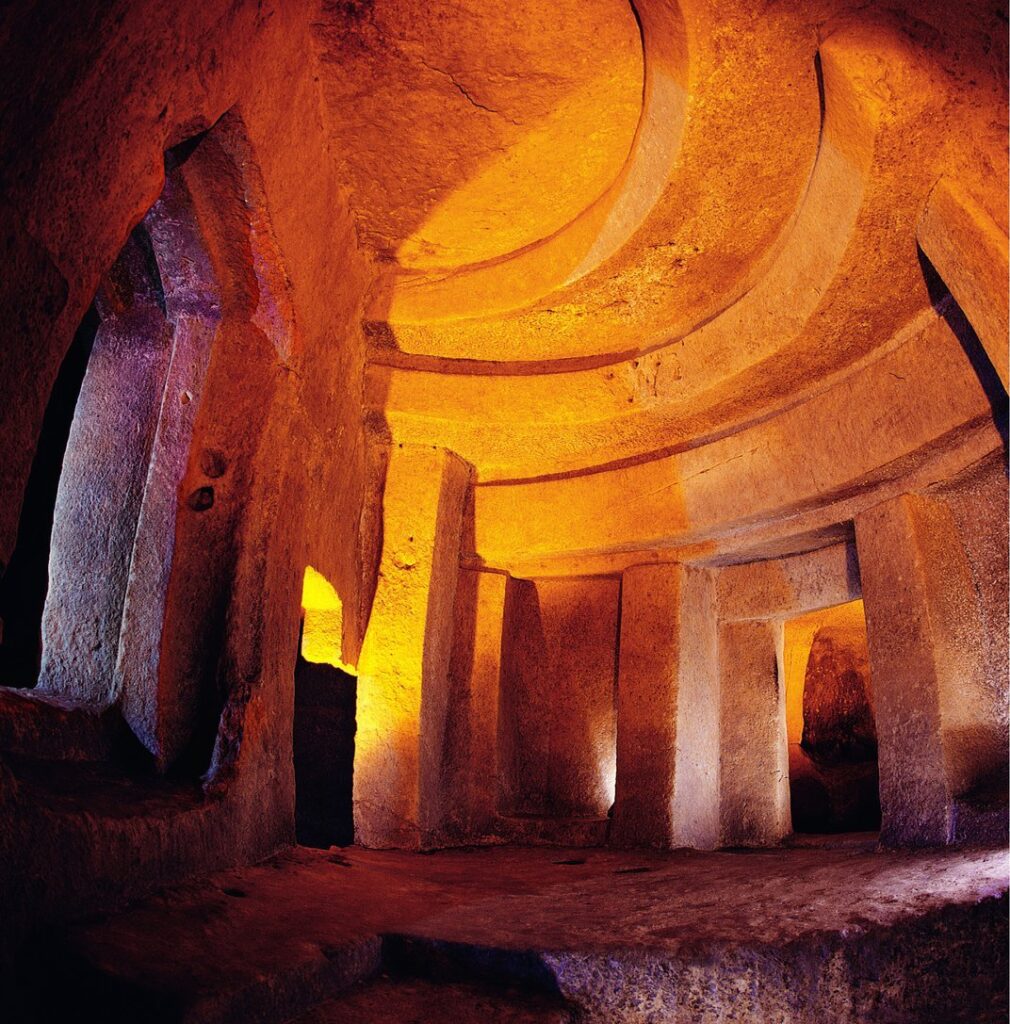

Several chambers are still decorated with black and white checkerboards and red ochre spirals and honey-combs, the only prehistoric paintings found on the island. Corbeled ceilings hint at how the ancient people of Malta supported roofs on the abundant above-ground buildings, now in ruins, found throughout the islands. “[It] gives us a chance to see what [the Hypogeum’s] contemporary temple structures might have looked like on the inside,” says Heritage Malta curator MariaElena Zammit.

According to Zammit, the Hypogeum and its artifacts held up over the millennia largely thanks to its encapsulation. “The Hypogeum is completely underground, completely closed, so it’s humid,” she says.

That moisture “keeps the salt in the stone soluble, preventing flaking. In other [temples throughout Malta], the surface is dissolving in places… [The Hypogeum] is held together by humidity.”

Without Heritage Malta’s careful control, the very presence of visitors to the ancient site would endanger its preservation. Curious fingertips leave behind visible oils that degrade any coloring and even the limestone itself.

Pathway-illuminating artificial lights encourage the growth of microorganisms, and the daily succession of warm, breathing bodies alters CO2 levels, airflow, temperature and humidity. So, while guides encourage tourists to play with the acoustics in the “Oracle Chamber,” visitors are prohibited from speaking directly into the echoing niche.

Preservation efforts first began in earnest in 1991, when the site closed for nearly a decade. The project resulted in walkways, visitor limitations, regulation of artificial light levels and an early but now outdated environmental control system.

More intensive monitoring began in 2022, as part of a grant from the European Economic Area to preserve the Unesco site for future generations, and those data, collected over a period of six years, provided the basis for the new environmental management system.

The Hypogeum’s newest preservation efforts include both passive and active measures, from improved insulation to better control humidity and temperature to modernized technology for studying microorganism growth and tracking real-time changes to the site’s microclimate. “Data will continue to be gathered and analyzed to continually assess the performance of the system installed, as well as [to] monitor the behavior of the site,” says Zammit.

Many of the changes won’t be visible to visitors: Ducts hide behind walls and the air handling units and chillers sit atop the visitor’s center roof. However, tourists will find a cleaner, more modern visitor center with high-pressure laminate panels, replacing mold-prone carpeting, and a new buffer system that gradually increases humidity between the welcome area and the main site.

The most exciting change for visitors will be the enhanced interpretation and virtual tour option. In 2000 after its first major preservation efforts, Heritage Malta limited site tours to 80 individuals per day. That number still stands, so visitors must book weeks or even months in advance to tour the Hypogeum in person.

Furthermore, low lighting and slick walkways render the site inaccessible to people in wheelchairs or with limited mobility. To help meet demand, the visitor’s center is now equipped with audiovisual technology that allows an additional 70 people to virtually tour the site daily from its lobby.

“Thus,” says Zammit, “Heritage Malta will be implementing its mission by making the site more accessible to more members of the community.”