Researchers “shocked” to discover 2,000-year-old Egyptian mummy was a pregnant woman

A mummified fetus identified within the leathery womb of an ancient Egyptian pregnant mummy was preserved for more than 2,000 years. Now, scientists have described the unusual processes that led to its preservation.

The Warsaw Mummy Project was launched in 2015 by a team of bio-archaeologists from the University of Warsaw. Their website says they aim to “thoroughly examine human and animal mummies from ancient Egypt at the National Museum in Warsaw.”

In April 2021, the BBC announced that a team of Warsaw Project researchers published an article in the Journal of Archaeological Science revealing the first documented case of a pregnant ancient Egyptian mummy and its mummified fetus.

The 2,000-year-old mummy, currently on display at the National Museum in Warsaw, was at first believed to be the remains of Hor Djehuti, a High Priest of Amun from the time of Ahmose I who lived at the beginning of the 18th Dynasty (1539 to 1292 BC).

However, in 2016, the Warsaw Project announced that the mummy was in fact that of an embalmed pregnant woman who was in the 26th to 30th week of her pregnancy when she died and was mummified!

Back in April 2021 we covered the publication of the scientist’s first study of the pregnant mummy .

At that time, Dr. Wojciech Ejsmond, lead author from the Polish Academy of Sciences, told The Sun that while mummies of babies were found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, this was the first time a pregnant woman has been preserved with soft tissue.

In April, Dr. Ejsmond said “more research is needed.” Now, the same team is back in the headlines having done the aforementioned research on the mummified fetus and they say the mysteries of the pregnant mummy only exist because of an unusual chemical process that led to the fetus being “pickled” and trapped in time.

Professor Ożarek-Szilke is co-director of the Warsaw Mummy Project. In a new paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science , the bio-archaeologist explained that to dry the pregnant woman’s dead body the embalmers covered her with natron, a natural compound of sodium salts that was used extensively in prehistory across Egypt, Middle East and Greece.

The powder was mostly used like baking-soda in cooking, medicine and agriculture, but it also had applications in glass-making and mummification.

Natron acts as a natural disinfectant and desiccating (drying) agent and it was the primary ingredient used in the ancient Egyptian mummification process .

After removing the organs and packing the internal cavities with dry natron, the body tissues were preserved. Then, the cadaver was packed with dry Nile mud, sawdust, lichen and dry cloths to make it more flexible in the afterlife.

The scientists wrote in the new study that when the natron was spread over the pregnant woman “it caused formic acid and other compounds” to manifest inside the woman’s uterus, creating the perfect conditions for preserving the fetus.

Gardeners know all too well, as do doctors, that acid and alkaline levels (pH) in nature determines the success of all organic growth. PH is a measure of the relative amount of free hydrogen and hydroxyl ions in water: with the more free hydrogen ions making for greater acidity.

During life, high pH (acid) in your blood it’s called alkalosis, while low pH is called acidosis, and both can lead to severe kidney complications. In the case of the mummified pregnant woman the increased acidity served to preserve the fetus.

Because of several chemical processes related to decomposition, say the scientists, the pH level inside the woman’s body shifted from an alkaline to a more acidic environment.

The new paper explains that these acids caused the minerals trapped within the tiny fetal bones to dry out and over time they “mineralized” or “pickled.”

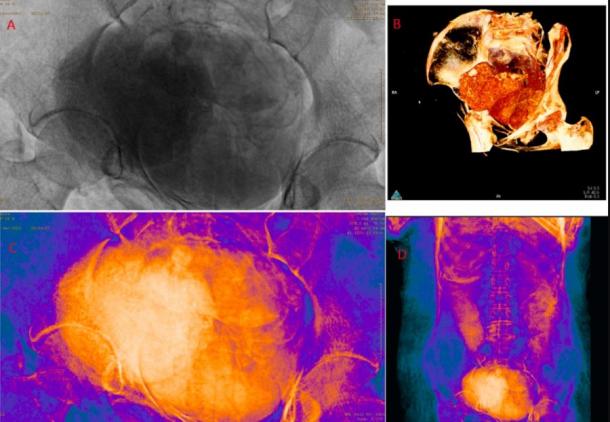

Dr. Ożarek-Szilke explained that the scans of the ancient Egyptian mummified fetus show the fetus’ “mineralized skull,” which developed the fastest. The hands and feet also appear on scans but these never formed with bones, but left behind only dried tissues.